THE TRAIL THAT CHANGED TEXAS HISTORY.

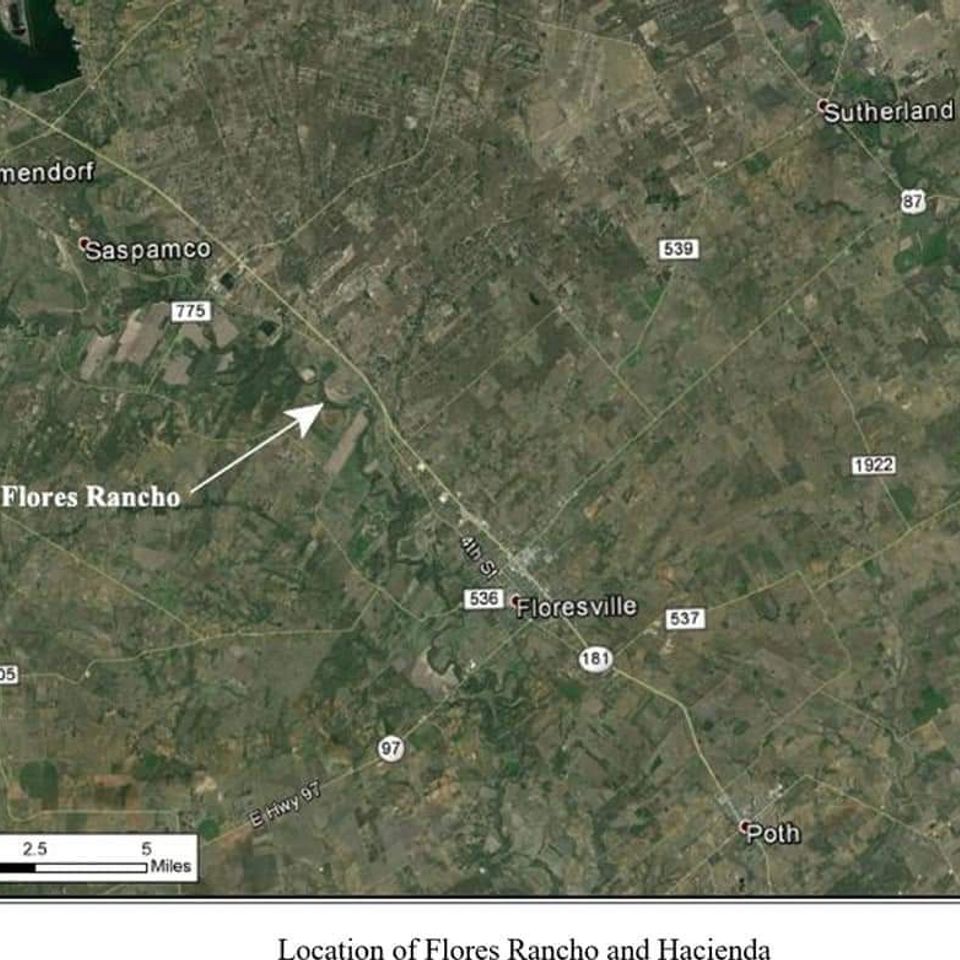

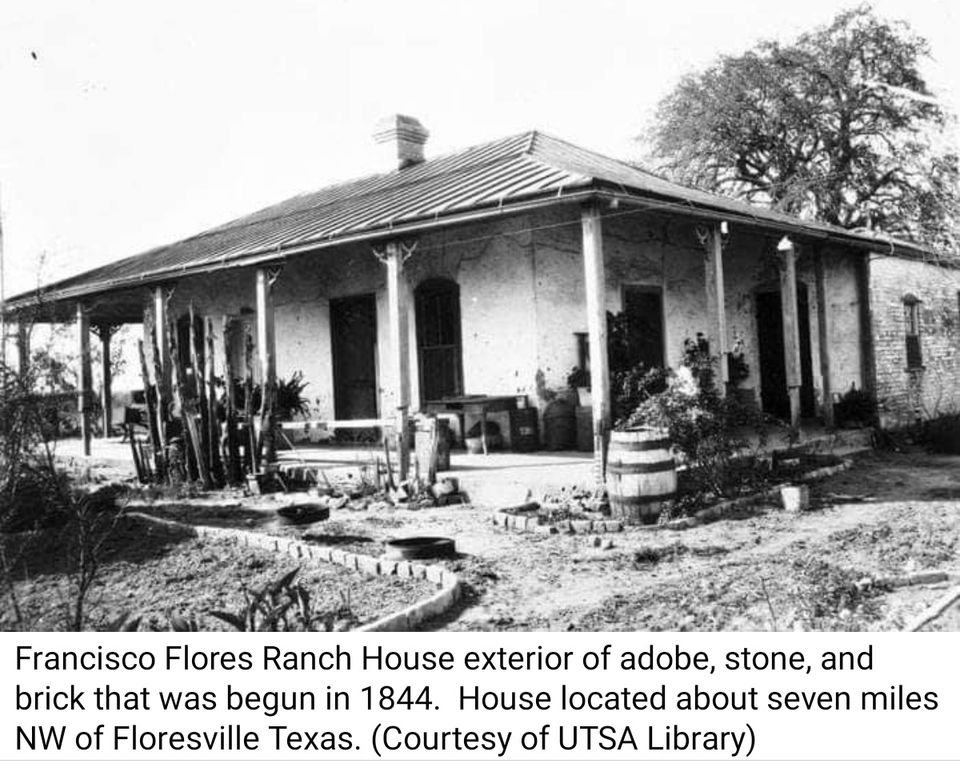

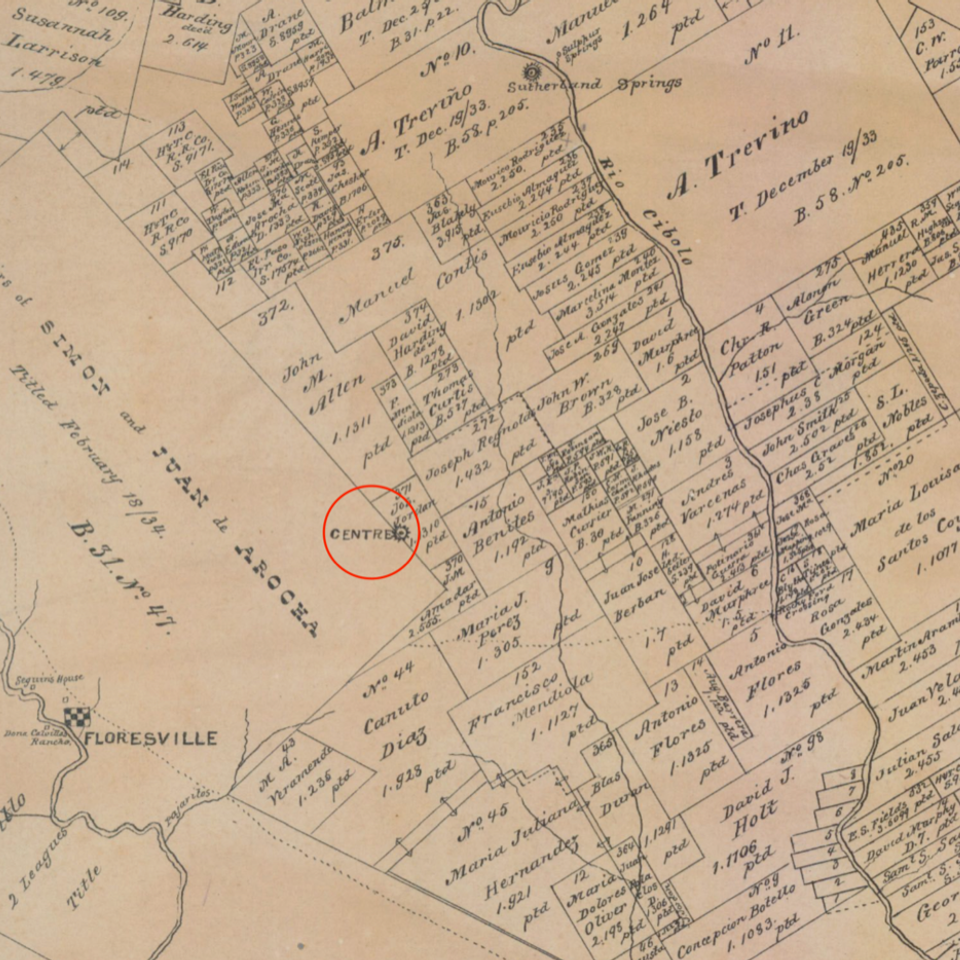

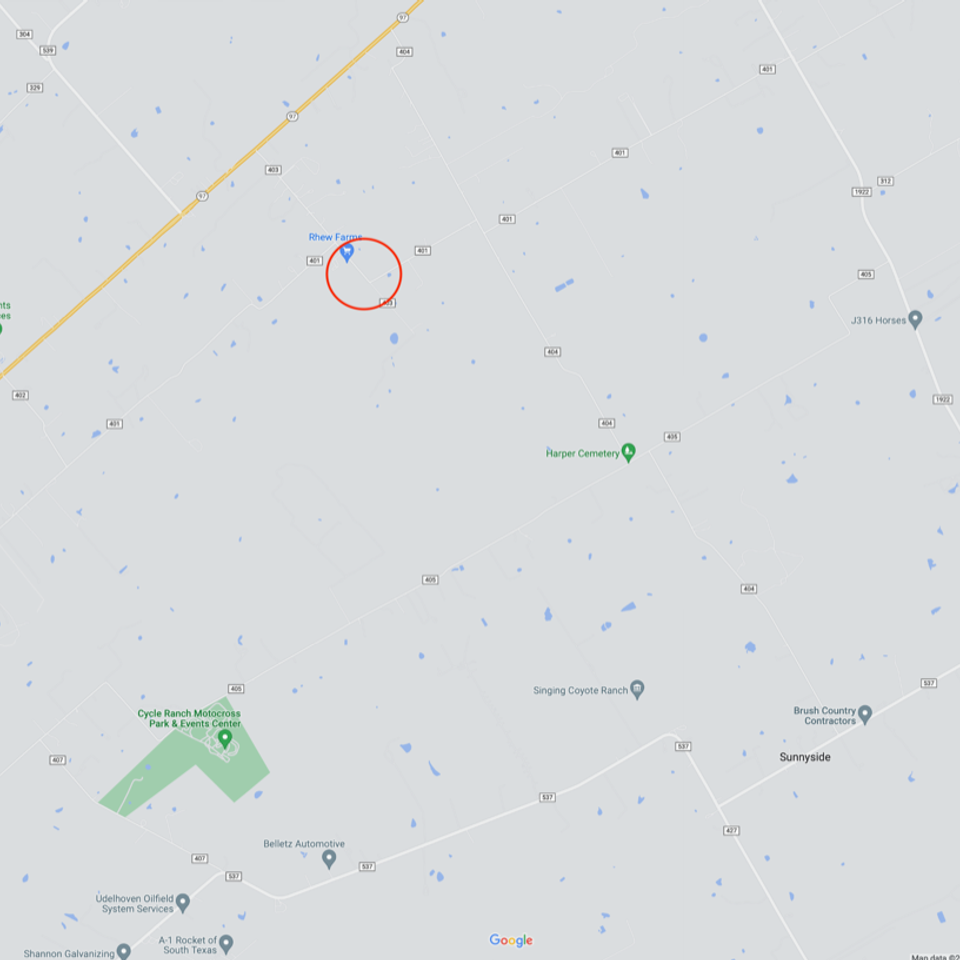

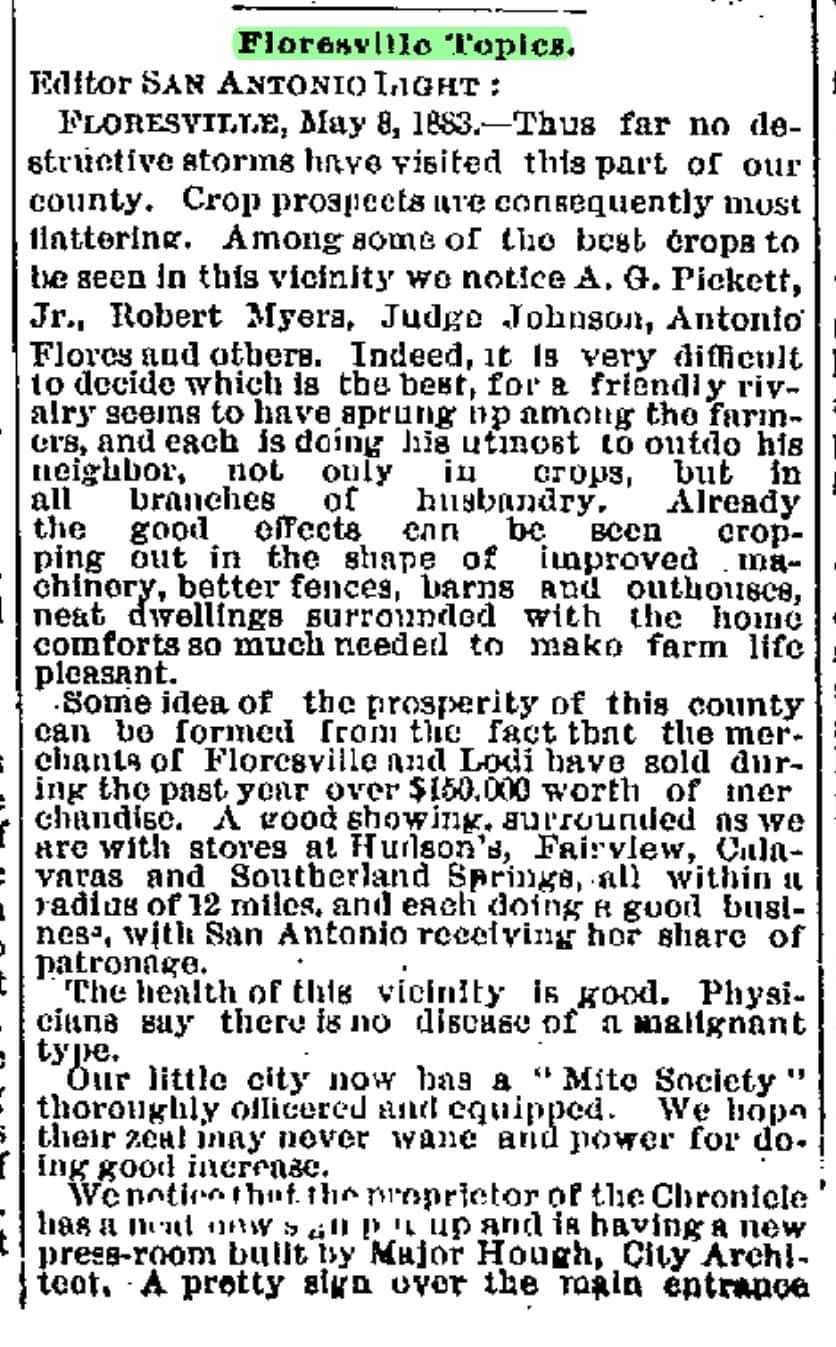

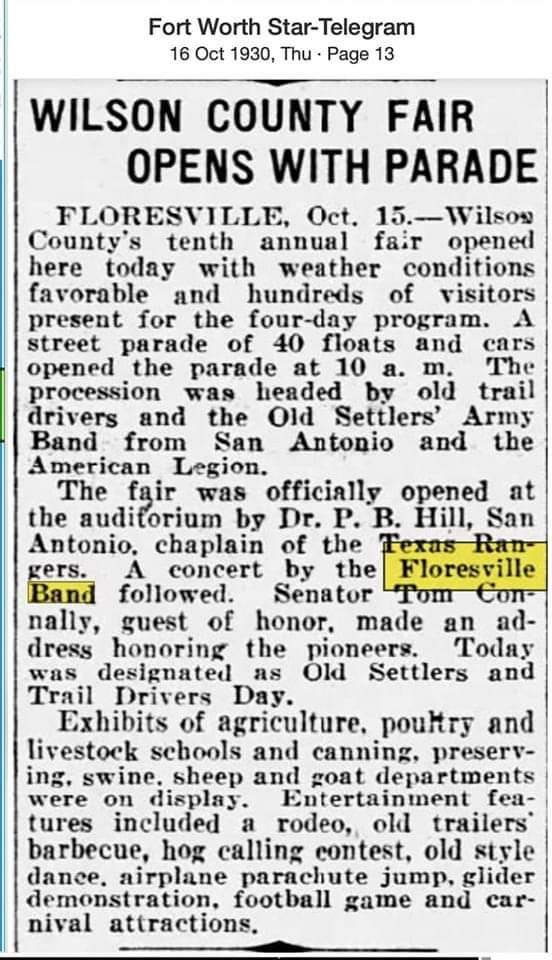

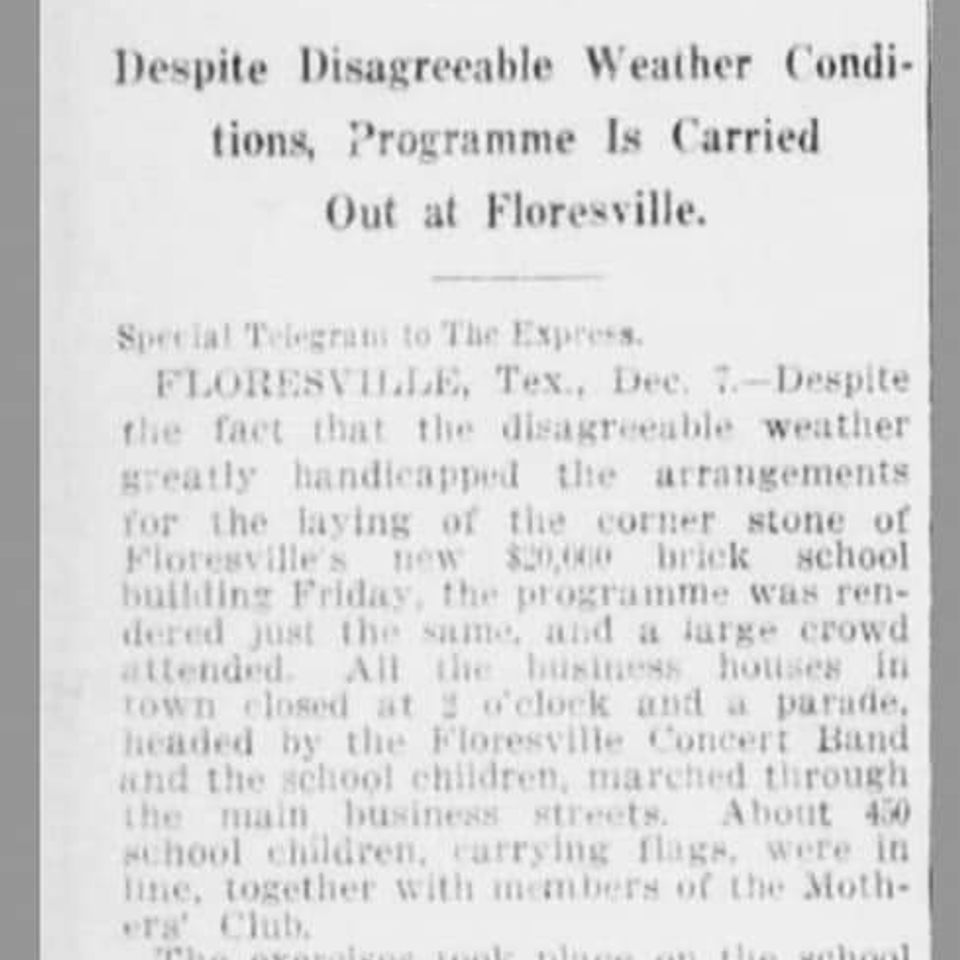

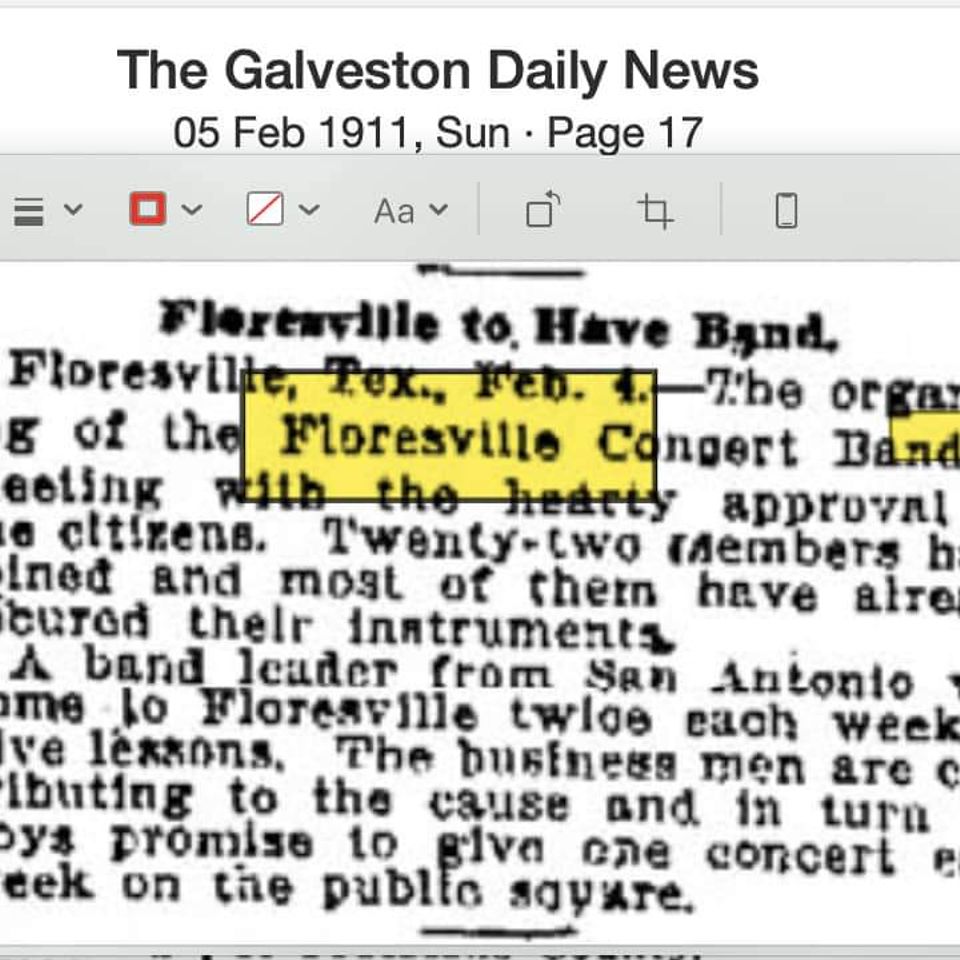

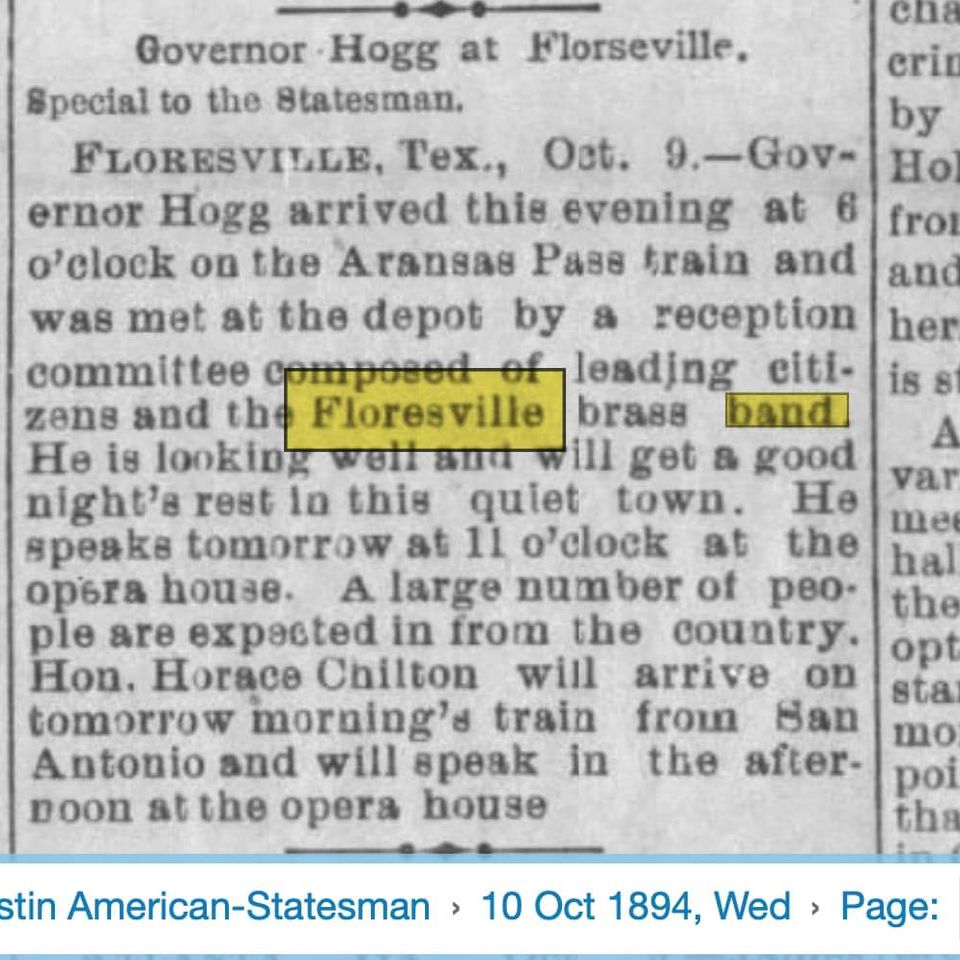

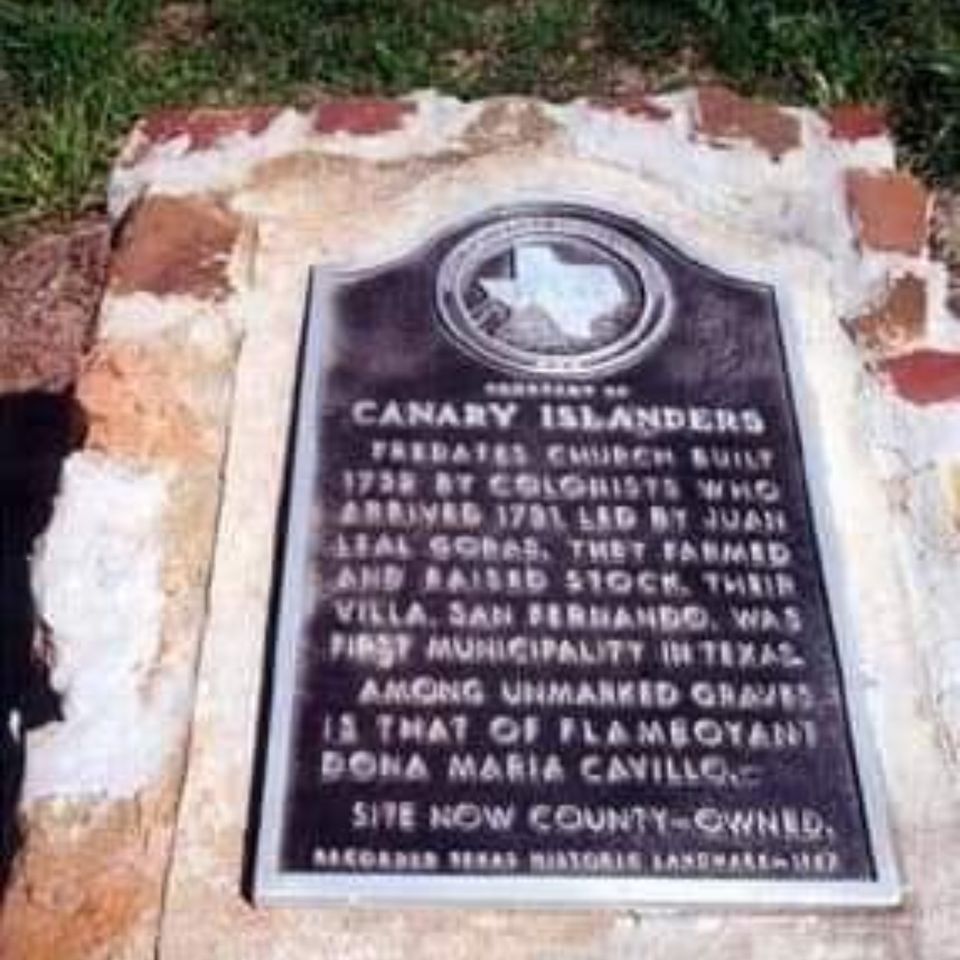

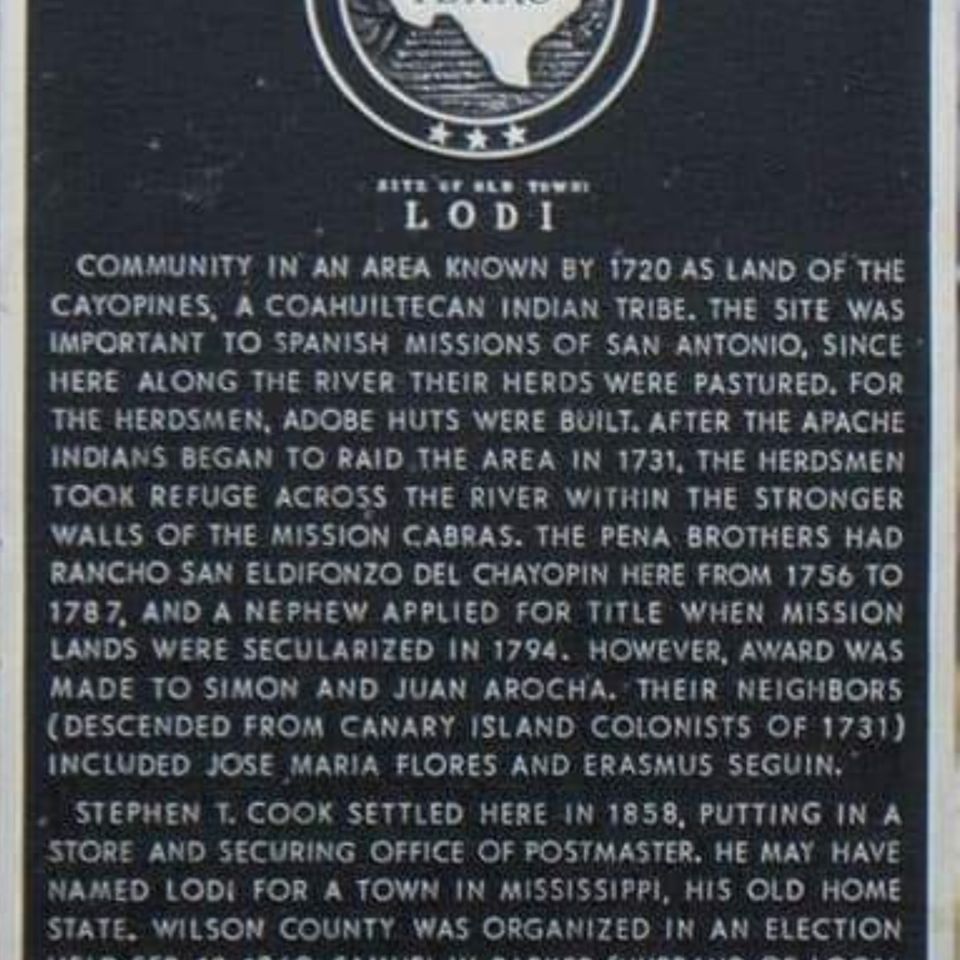

THE TRAIL THAT CHANGED TEXAS HISTORY... and Wilson County Texas was a part of it. Rich grasslands attracted Canary Island immigrants here in the 1730s. A state historic site recalls that era at the stabilized ruins of Rancho de las Cabras, a ranching outpost that served one of San Antonio's missions. Once called Lodi, the town was named Floresville in honor of an early Canary Island family and became the seat of Wilson County. The 1884 Italianate courthouse designed by noted architect Alfred Giles sits on the downtown square, along with a huge peanut statue honoring the local agri-product.

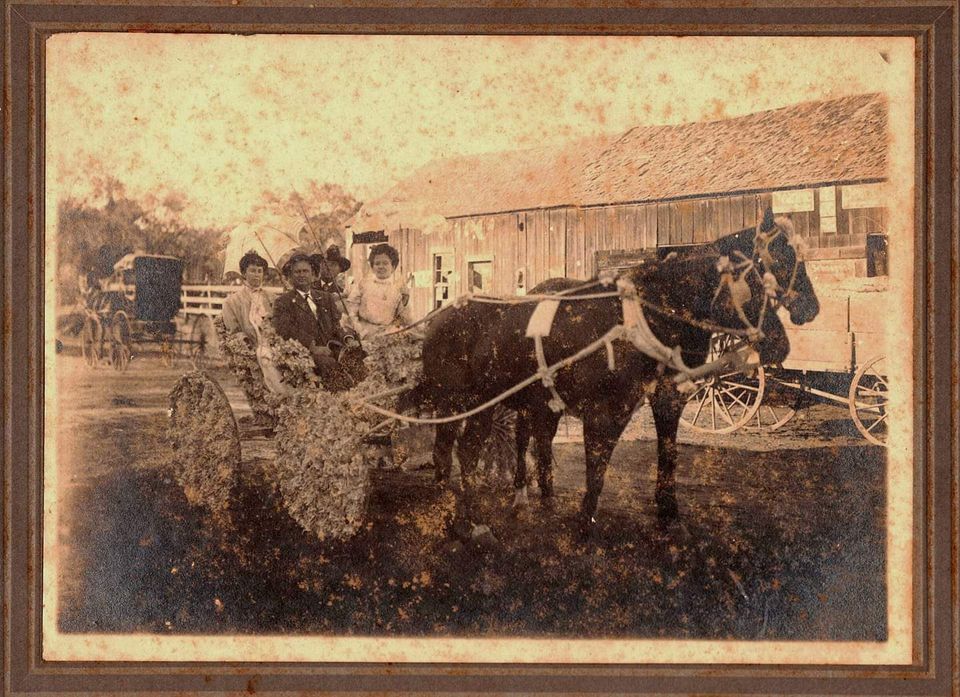

Chisholm Trail history was made here by John Oatman Dewees, a leading cattleman during the trail driving years, Dewees owned a prominent ranch in Wilson and Atascosa counties. He partnered with James F. Ellison in 1869, and together they moved a total of more than 400,000 cattle up the trail by 1877. The ruins of Rancho de las Cabras are four miles south of Floresville, at the junction of Picosa Creek and the San Antonio River. The ruins, originally a colonial ranch associated with Mission Espada near San Antonio, are now part of San Antonio Missions National Historical Park.

By the end of the Civil War, Texas hadn't much left to offer a newly united country...except BEEF! Historians have long debated aspects of the Chisholm Trail's history, including the exact route and even its name. Although a number of cattle drive routes existed in 19th century America, none have penetrated the heart of popular imagination like the Chisholm Trail, especially in Texas.

As early as the 1840s, Texas cattlemen searched out profitable markets for their longhorns, a hardy breed of livestock descended from Spanish Andalusian cattle brought over by 16th century explorers, missionaries, and ranchers. But options for transporting the cattle were few. The solution lay north, where railroads could carry livestock to meat packing centers and customers throughout the populated east and far west. Enter Joseph G. McCoy from Illinois, who convinced the powers-that-be at the Kansas Pacific Railway company to allow him to build a cattle-shipping terminal in Abilene, Kansas.

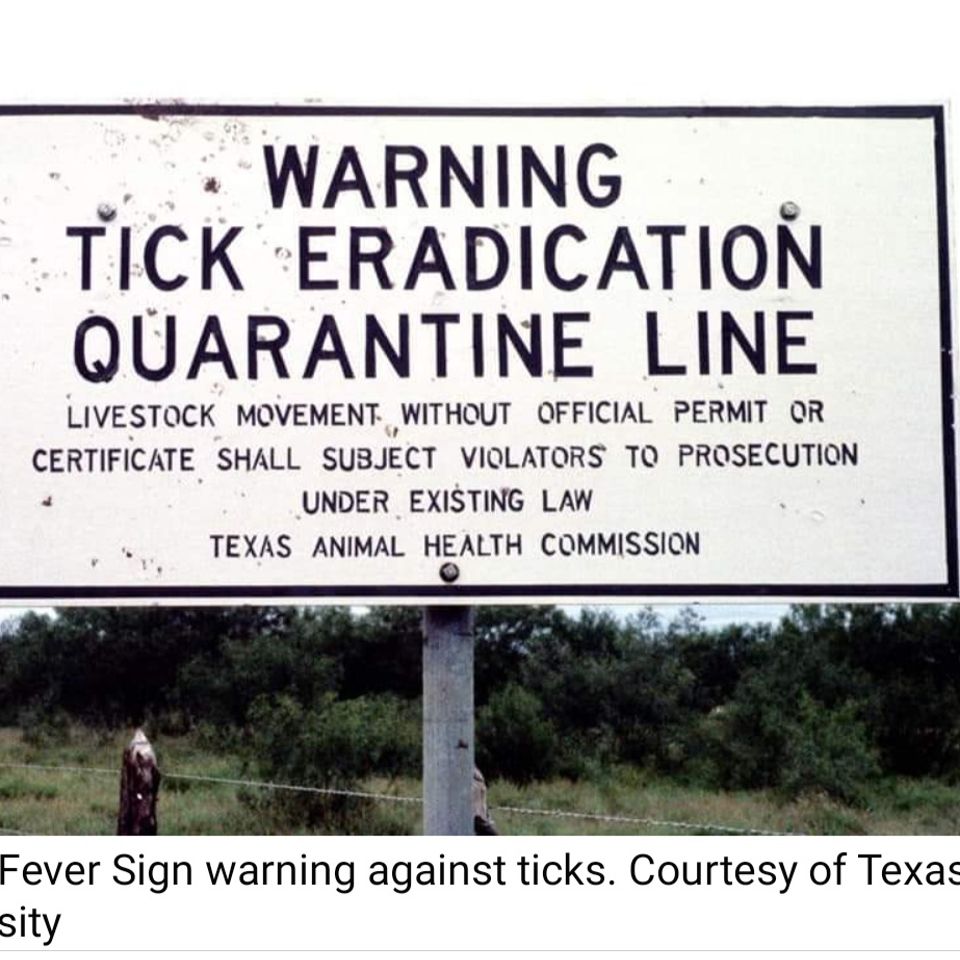

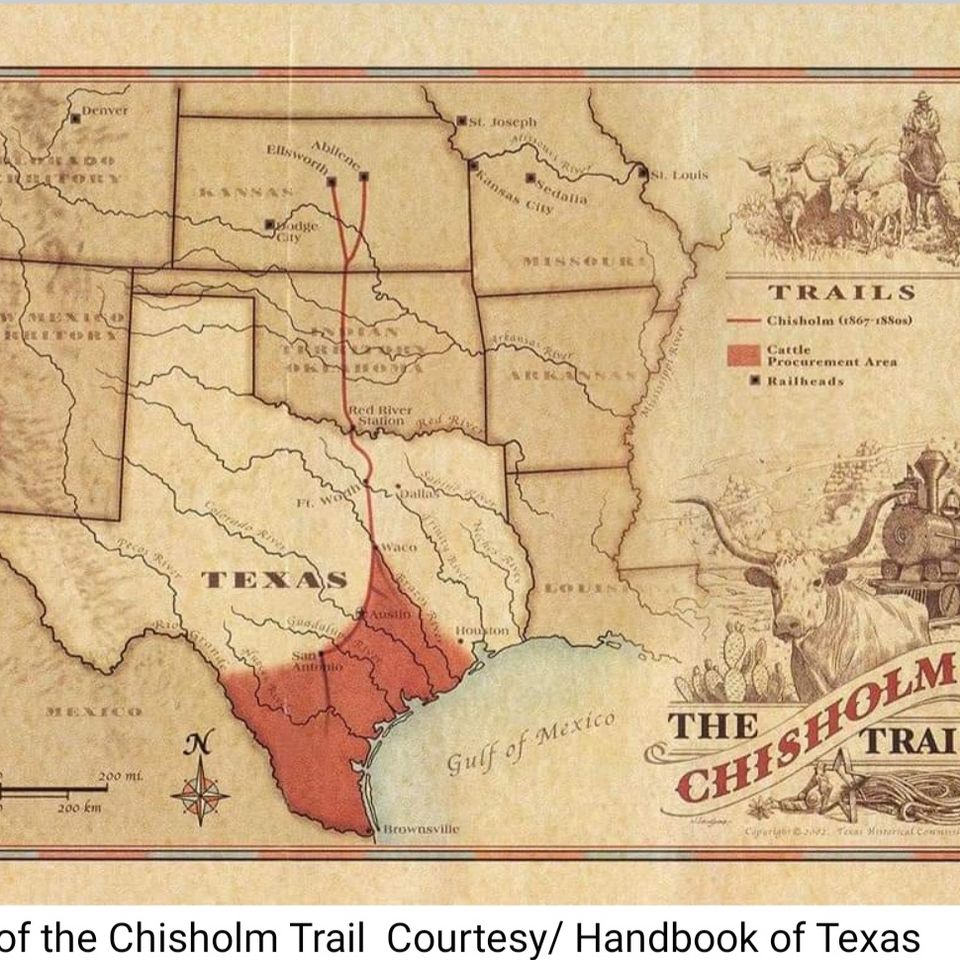

The new route cattle drivers used to push the longhorn to Kansas shipping points became known as the Chisholm Trail, named for Jesse Chisholm, a Scot-Cherokee trader who had established the heart of the route while transporting his trade goods to Native American camps, and it eventually inspired the link between the great movement of longhorns from South Texas to central Kansas to the Chisholm name. Before the Chisholm was shut down in the late 1880s (by a combination of fences and a Texas fever quarantine) the trail accommodated more than five million cattle and more than a million wild mustangs, considered the largest human-driven animal migration in history.

The Chisholm Trail was the major route out of Texas for livestock. Although it was used only from 1867 to 1884, the longhorn cattle driven north along it provided a steady source of income that helped the impoverished state recover from the Civil War. Youthful trail hands on mustangs gave a Texas flavor to the entire ange cattle industry of the Great Plains and made the cowboy an enduring folk hero.

When the Civil War ended, the state's only potential assets were its countless longhorns, for which no market was available—Missouri and Kansas had closed their borders to Texas cattle in the 1850s because of the deadly Texas fever they carried. In the East was a growing demand for beef, and many men, among them Joseph G. McCoy of Illinois, sought ways of supplying it with Texas cattle. In the spring of 1867 he persuaded Kansas Pacific officials to lay a siding at the hamlet of Abilene, Kansas, on the edge of the quarantine area. He began building pens and loading facilities and sent word to Texas cowmen that a cattle market was available. That year he shipped 35,000 head; the number doubled each year until 1871, when 600,000 head glutted the market.

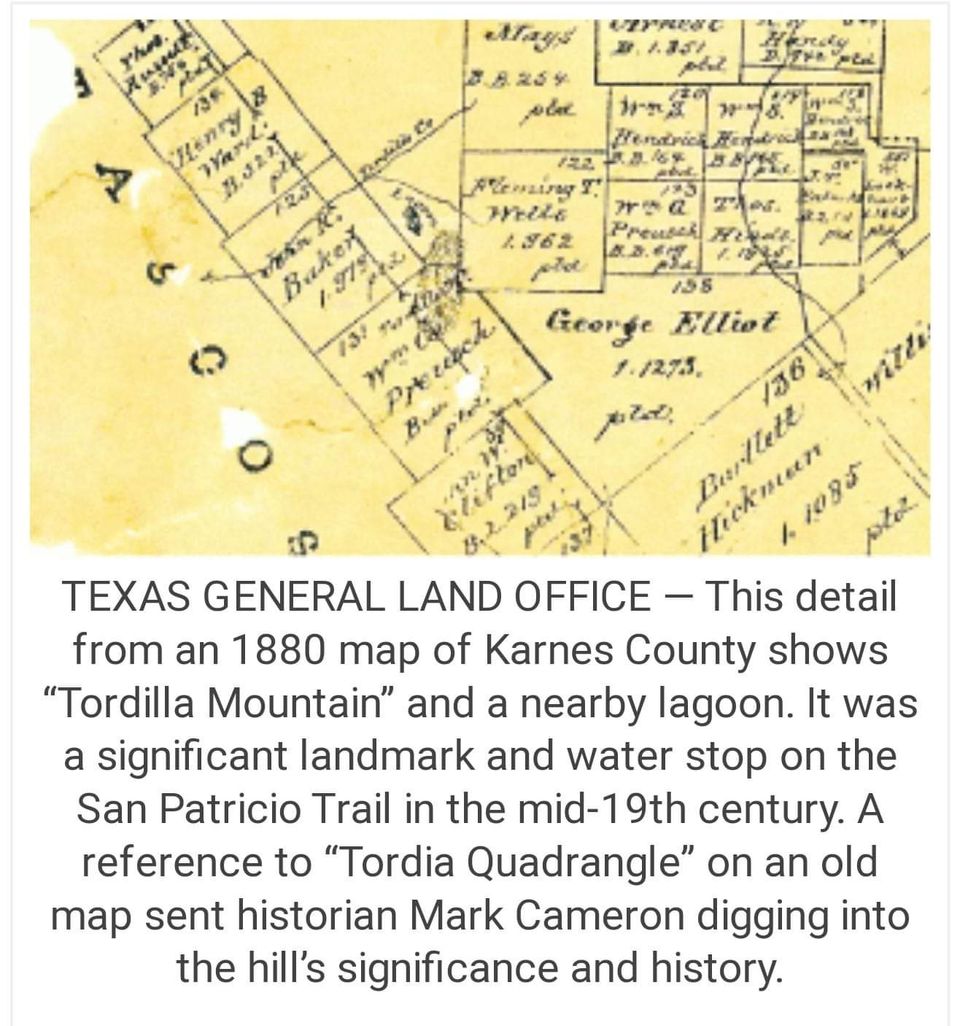

The first herd to follow the future Chisholm Trail to Abilene belonged to O. W. Wheeler and his partners, who in 1867 bought 2,400 steers in San Antonio. They planned to winter them on the plains, then trail them on to California. At the North Canadian River in Indian Territory they saw wagon tracks and followed them. The tracks were made by Scot-Cherokee Jesse Chisholm, who in 1864 began hauling trade goods to Indian camps about 220 miles south of his post near modern Wichita. At first the route was merely referred to as the Trail, the Kansas Trail, the Abilene Trail, or McCoy's Trail. Though it was originally applied only to the trail north of the Red River, Texas cowmen soon gave Chisholm's name to the entire trail from the Rio Grande to central Kansas. The earliest known references to the Chisholm Trail in print were in the Kansas Daily Commonwealth of May 27 and October 11, 1870. On April 28, 1874, the Denison, Texas, Daily News mentioned cattle going up "the famous Chisholm Trail."

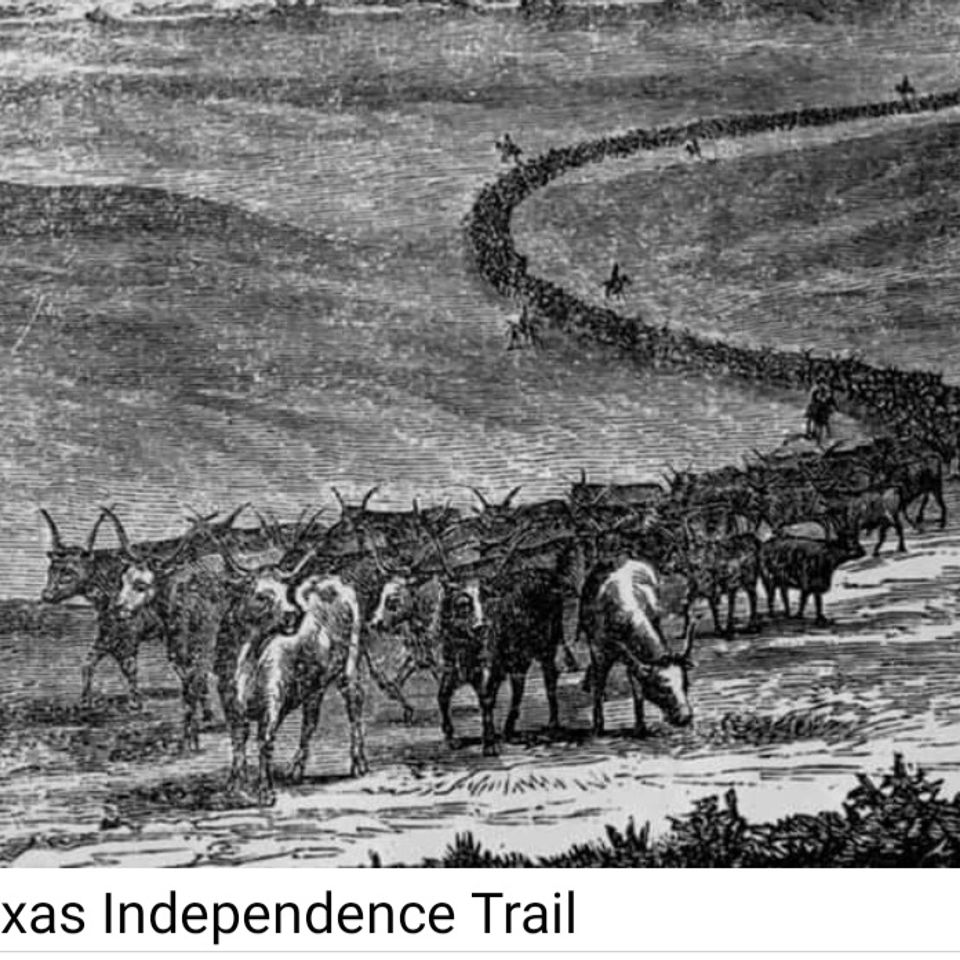

The herds followed the old Shawnee Trail by way of San Antonio, Austin, and Waco, where the trails split. The Chisholm Trail continued on to Fort Worth, then passed east of Decatur to the crossing at Red River Station. From Fort Worth to Newton, Kansas, U.S. Highway 81 follows the Chisholm Trail. It was, Wayne Gard observed, like a tree—the roots were the feeder trails from South Texas, the trunk was the main route from San Antonio across Indian Territory, and the branches were extensions to various railheads in Kansas. Between 1871, when Abilene ceased to be a cattle market, and 1884 the trail might end at Ellsworth, Junction City, Newton, Wichita, or Caldwell. The Western Trail by way of Fort Griffin and Doan's Store ended at Dodge City.

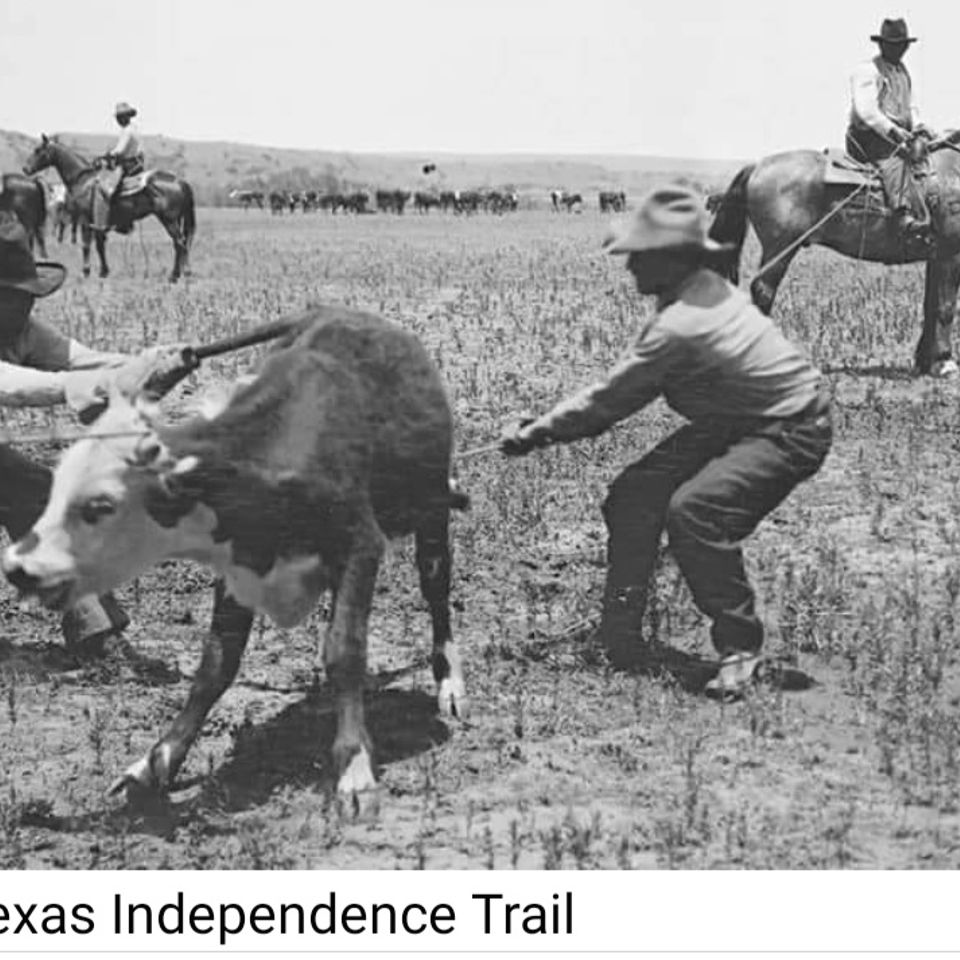

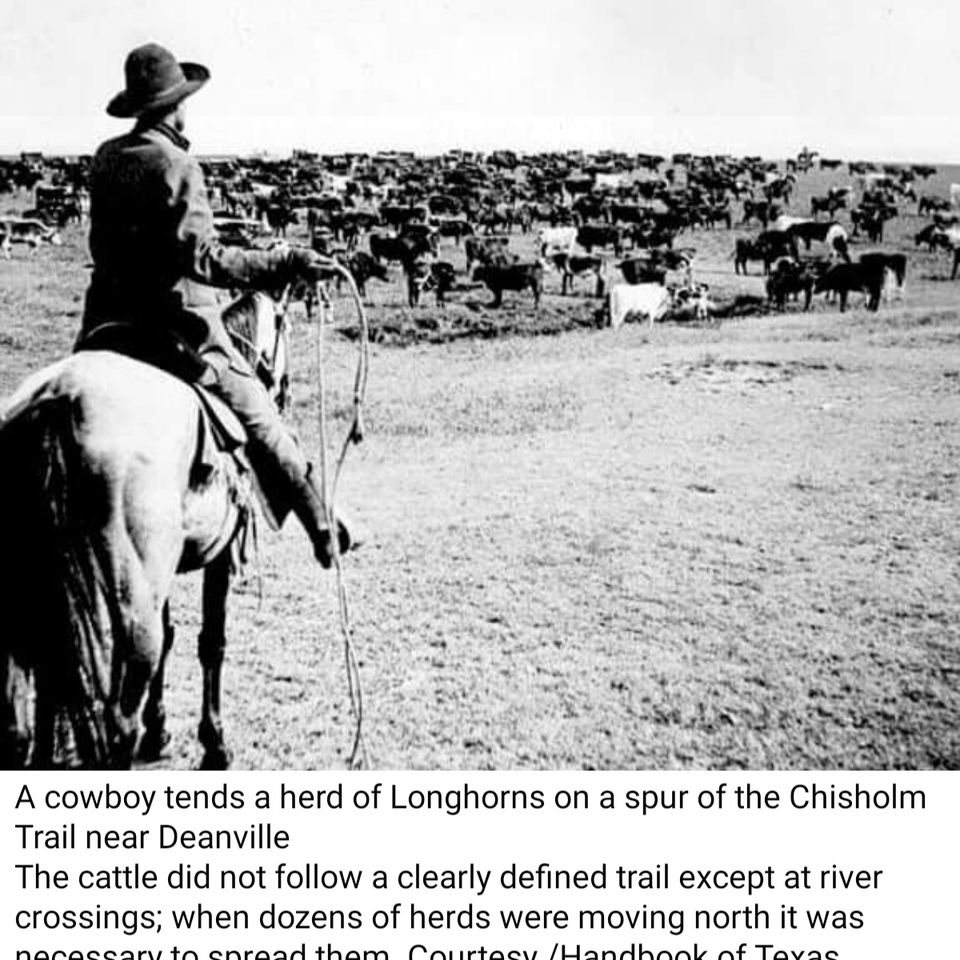

The cattle did not follow a clearly defined trail except at river crossings; when dozens of herds were moving north it was necessary to spread them out to find grass. The animals were allowed to graze along for ten or twelve miles a day and never pushed except to reach water; cattle that ate and drank their fill were unlikely to stampede. When conditions were favorable longhorns actually gained weight on the trail. After trailing techniques were perfected, a trail boss, ten cowboys, a cook, and a horse wrangler could trail 2,500 cattle three months for sixty to seventy-five cents a head. This was far cheaper than shipping by rail.

The Chisholm Trail led to the new profession of trailing contractor. A few large ranchers such as Capt. Richard King and Abel (Shanghai) Pierce delivered their own stock, but trailing contractors handled the vast majority of herds. Among them were John T. Lytle and his partners, who trailed about 600,000 head. Others were George W.laughter and sons, Snyder Brothers, Blocker Brothers, and Pryor Brothers. In 1884 Pryor Brothers contracted to deliver 45,000 head, sending them in fifteen separate herds for a net profit of $20,000.

After the Plains tribes were subdued and the buffalo decimated, ranches sprang up all over the Plains; most were stocked with Texas longhorns and manned by Texas cowboys. Raising cattle on open range and free grass attracted investments from the East and abroad in partnerships such as that of Charles Goodnight and Irish financier John Adair or in ranching syndicates such as the Scottish Prairie Land and Cattle Company and the Matador Land and Cattle Company. Texas tried to outlaw alien land ownership but failed. The XIT Ranch arose when the Texas legislature granted the Capitol Syndicate of Chicago three million acres for building a new Capitol.

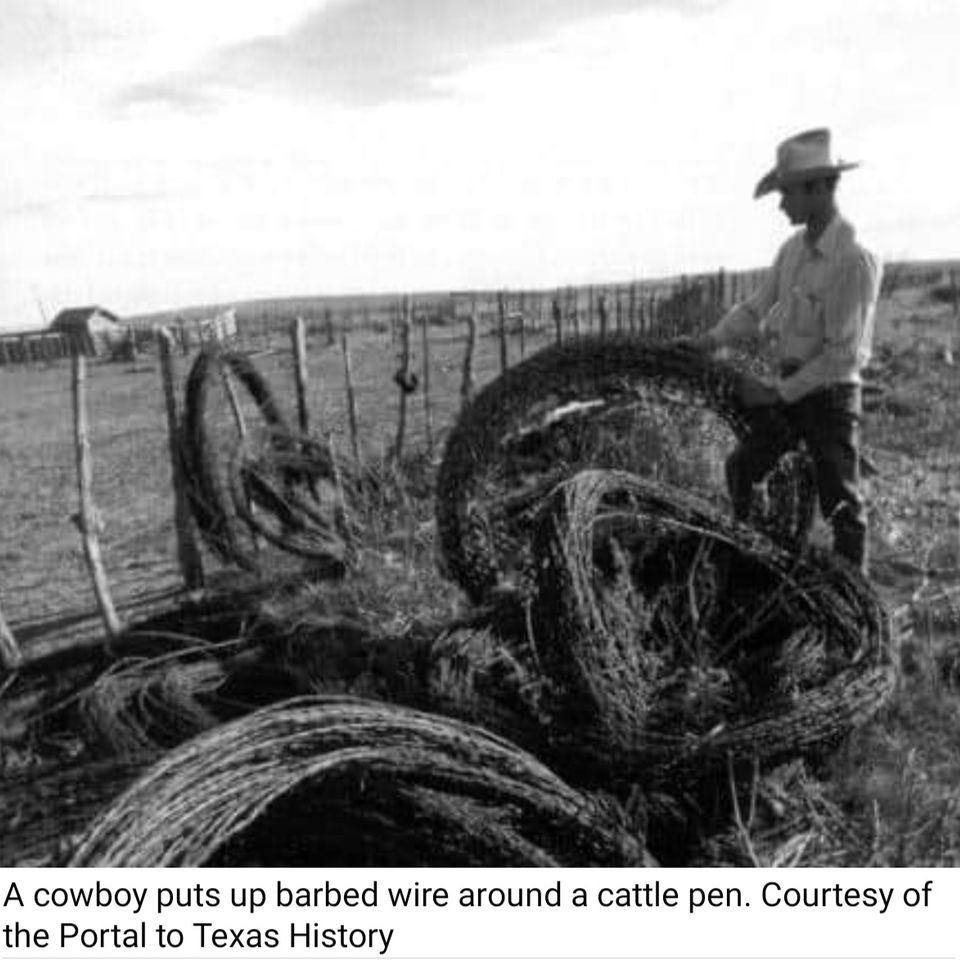

The Chisholm Trail was finally closed by barbed wire and an 1885 Kansas quarantine law; by 1884, its last year, it was open only as far as Caldwell, in southern Kansas. In its brief existence it had been followed by more than five million cattle and a million mustangs, the greatest migration of livestock in world history.

***********************

Courtesy/ Texas Independence Trail

Courtesy/ Portal to Texas History

Courtesy / Handbook of Texas