by Barbara J. Wood

STAGE TRAVEL

STAGE TRAVEL IN SAN ANTONIO TEXAS AREA

During the 18th century, the land that would become Texas was administered by Spain. El Camino Real and the La Bahia Road passed through San Antonio. Both were roads that connected the seat of government in Mexico to distant frontier boundaries with French Louisiana territories. These were primitive roads suitable for horses, men on foot and wooden oxcarts.

Through the 19th century, roads in Texas were dirt trails; rough and dusty at best, muddy and impassable at worst. These humble roads carried immigrants to new settlements, crops to market and soldiers to battle.

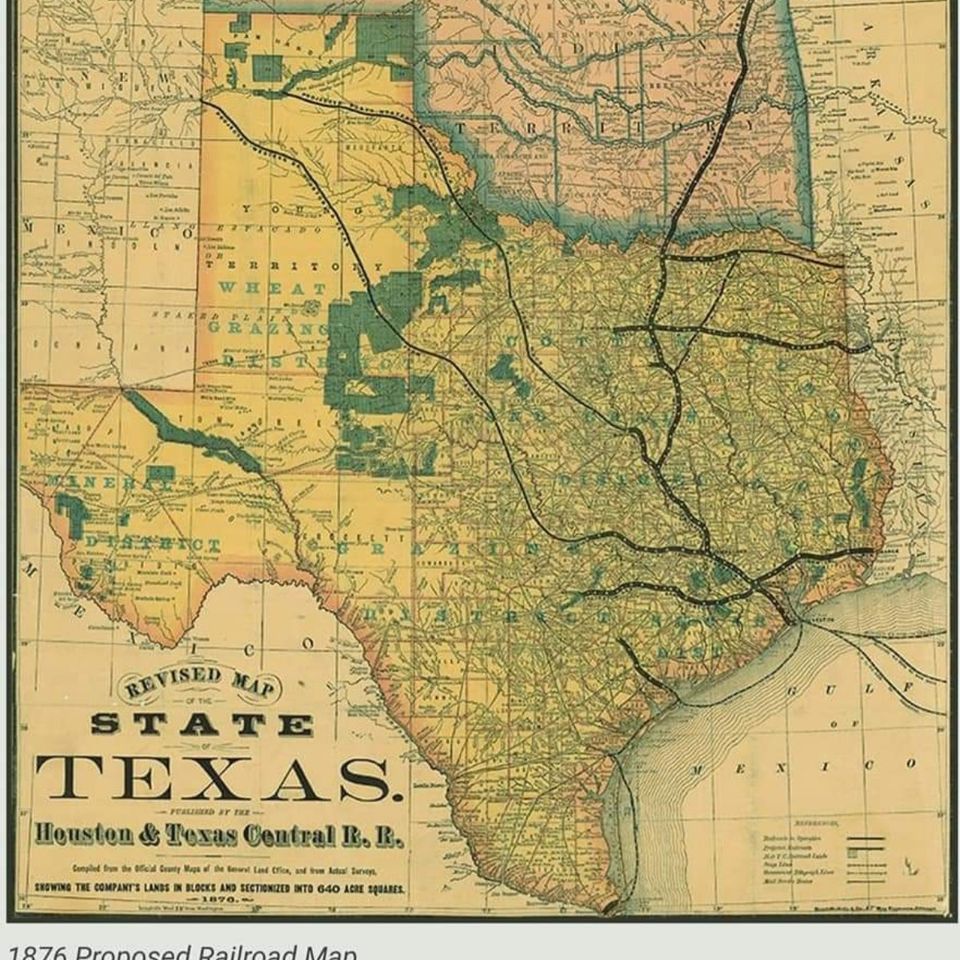

When Texas was admitted to the Union in 1845, there was a flurry of activity associated with creating a U.S. transcontinental route through its vast territory. San Antonio became a central hub for roads leading east and west. The roads created during the Mexican and Spanish administration of Texas were redirected and repurposed to connect the Gulf of Mexico to the east with the Pacific Ocean to the west.

Road building and maintenance were functions of county government acting as an extension of the Texas State Legislature. When the Texas State Legislature mandated the creation of "first class" roads between county seats, they defined a first class road as a path forty feet wide. Within that path smaller stumps (less eight inches in diameter) were to be cut off at ground level, larger stumps were rounded off to allow wagon wheels to pass over them. Second-class and third class roads were also defined in terms of width, thirty feet and twenty feet wide respectively.

Mail service was provided using these roads. At a time when news traveled as fast as the fastest horse, these dirt roads were the only connection Texans had to each other and to the rest of the world. The San Antonio newspapers (like other local papers) reprinted news from newspapers from around the country. These newspapers were delivered to them by mail.

Unreliable mail delivery was a persistent problem. Most central Texas mail arrived at the ports of Indianola and Galveston. Coordinating the schedule of stagecoaches with the arrival of ships often cause delays. In the fall of 1848, a San Antonio newspaper lamented that "We receive but three mails a week, in this, the most important and populous city in Western Texas, viz: two from Galveston by the roundabout way of Houston, Washington (on the Brazos), and Austin, and one from Castroville."

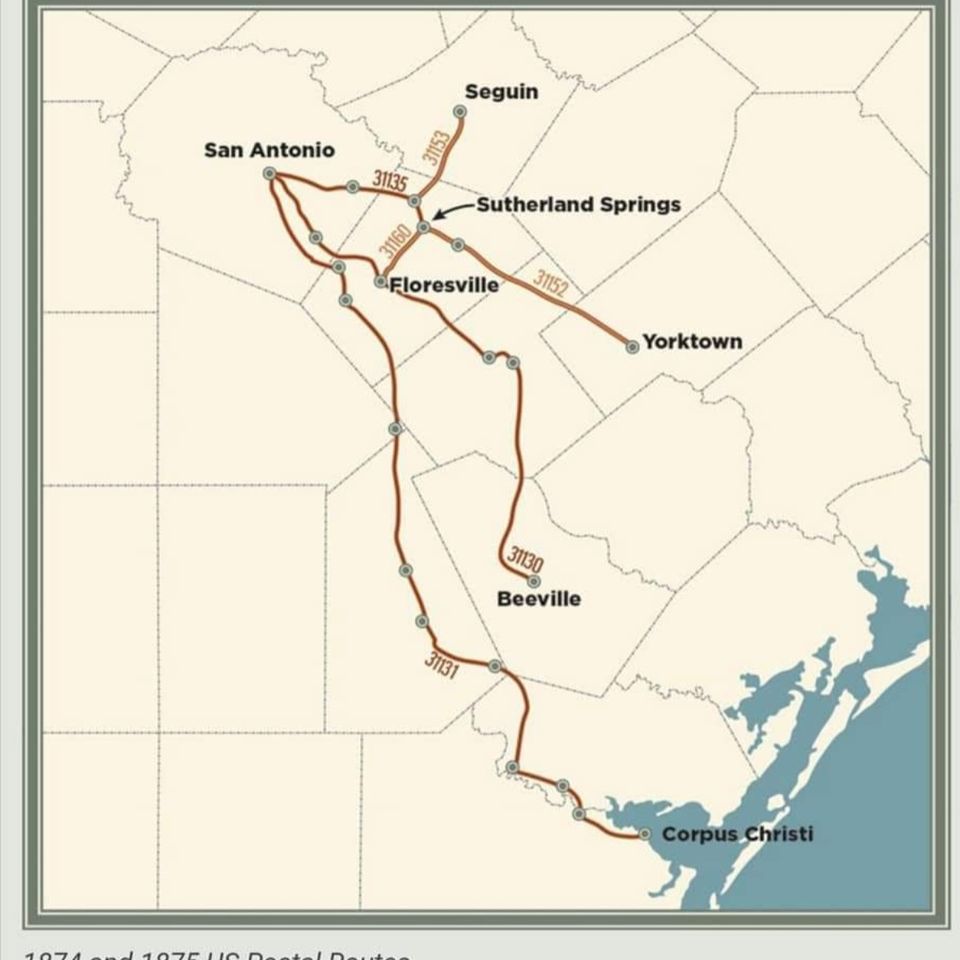

The Republic of Texas provided mail service by awarding contracts to winning bidders. With most of the population confined to the area of Austin's Colony, Harrisburg, and coastal and central Texas the earliest Texas mail routes were relatively short. On December 26,1835, (before the fall of the Alamo) John R. Jones, Postmaster General, under the authority of the General Council of Texas in San Felipe de Austin requested bids for mail routes throughout the New Republic. Route #14 was described as: "From Gonzales, by Sandies and Cibolo to Bejar, seventy-six miles, once in two weeks." When Texas became a part of United States, its mail contracts were included in the existing national bidding system for routes specified in the Congressional Record.

The location and names of villages were often associated with the establishment of post offices. The opening of a post office could insure that one village would thrive, while another might disappear. At first, delivery of newspapers and mail were the main function of post offices. After the Civil War, the post office provided a safe means for transferring money through the issuance of money orders. For remote settlers, the post office provided a rudimentary form of banking.

Mail coaches traveled in "stages", stopping at designated locations along a route to pick up and deliver mail. These early mail coaches also carried passengers. While the driver operated the stagecoach, an additional employee collected passenger fares and dealt with the mail. This man sat beside the driver and carried a rifle or shotgun to protect the mail and passengers, creating the term "riding shotgun."

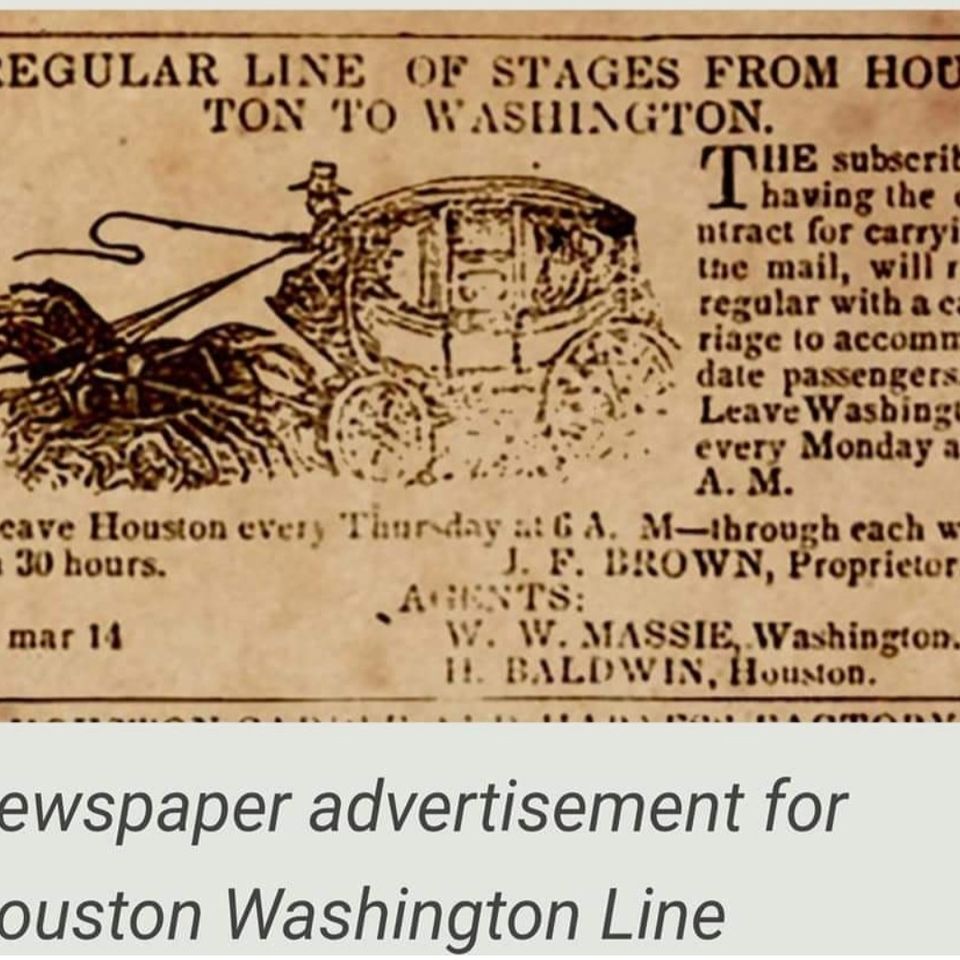

Newspaper advertisement for Houston Washington Line

A stagecoach travelled an average of 5 miles per hour. Depending on the condition of the road, availability of water, and the terrain, stage stops were established along a route to allow for a change of horses every 15 to 30 miles. Wells Fargo's six-horse Concord coaches traveled an average of 5 to 12 miles an hour. A Houston newspaper in 1845 advertised a line of stages from Houston to Washington on the Brazos that would carry mail and passenger through in 30 hours.

Early coaches were often two horse wagons with "drop-down" canvas covers. Later coaches were pulled by four horses, enclosed, and designed to provide comfort for the passengers. Brown and Tarbox and Harrison and McCullogh used four horse coaches for their stage line. In 1850, the Harrison and Brown stage line advertised four-horse, covered, nine passenger coaches. J.L. Allen advertised, "superior coaches, fine horses, polite and skillful drivers." D. A. Saltmarsh, an experienced stage operator from the East Coast, brought six fine Troy coaches (built in Troy, NY probably by Eaton & Gilbert) for his San Antonio to Port Lavaca line.

Additional options and services were constantly being offered to Texans traveling by stagecoach. Some company stage stops provided meals and accommodations for travelers. Stage lines charged for excess baggage that accompanied passengers; Tarbox and Brown, allowed a maximum of 30 pounds of baggage and charged 6 cents for each extra pound.

By the late 1840s, in the larger towns, stage offices/stops were located in hotels. The Houston House and The Old Capitol Hotel in Houston, John S. Harrison's Victoria Hotel, Brown's Hotel and the Guadalupe Hotel in Victoria, and Clegg's Hotel in Port Lavaca were all stage stops in the 1840s. In San Antonio during the mid 19th century, the Central Hotel, the Navarro House, the Plaza House and the Veramendi House were among the stage offices/stops available to the public. The scheduled routes of stage lines intersected in villages and towns, allowing for connections to destinations throughout Texas.

In 1847, John Sutherland (then a resident of Egypt, Texas) operated a stage line from Houston to Victoria via Richmond, Egypt, and Texana. Sutherland established a stage stop near Egypt adjacent to Sutherland's Ferry. In March of 1847, Sutherland listed his farm on a quarter league of land with the stage stand for sale. By 1849, he had moved to the Cibolo east of San Antonio where he created a stage stop, opened a post office and created the village first called Mineral Springs, then Sulphur Springs and finally Sutherland Springs.

In February of 1847, Brown and Tarbox established the Texas U.S. Mail Line with stagecoaches that traveled between Houston and San Antonio twice a week, stopping at Washington, Independence, La Grange, Bastrop, Austin, St. Marks, New Braunfels, and San Antonio. The trip from Houston to San Antonio took five days, and cost $20.00.

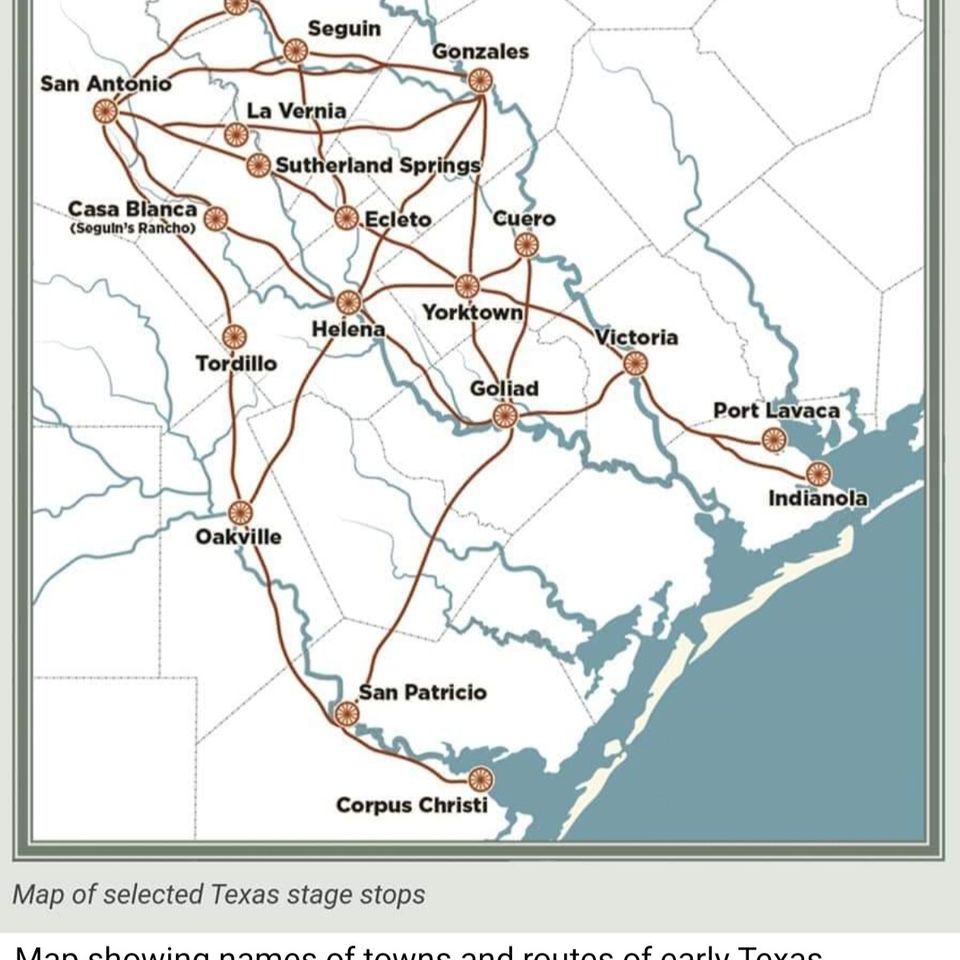

In October of 1847, Thomas Cooper announced plans for a stage line from Lavaca to San Antonio. The first day of travel would end in Victoria, the second in Cuero, the third in Gonzales, the fourth in Seguin, and the final day in San Antonio. The line would have first class mail carriages, capable of carrying ten passengers. In 1847, a freight line ran from Corpus Christi to San Antonio de Bexar; the cost to transport freight was $1.00 per 100 lbs. This line ran once every two weeks.

In 1850, a stage line ran from San Antonio to Corpus Christi, along the San Patricio Trail. The stage lines encountered persistent problems with Indians on this route. Theft of horses by Indians caused at least one line to discontinue service.

At this same time John S. Harrison and his brother-in-law, William H. McCulloch, began a stage line from Indian Point to Victoria. They later extended this line from Port Lavaca to New Braunfels. The line passed through Cuero, Gonzales, Seguin, and on to New Braunfels. The coach would leave Port Lavaca on Friday at 6 A.M. and arrived in New Braunfels at 4 P.M. on Monday at a cost of $10.00 for the entire trip. The Selma Stage Stop, now a Texas Historical Landmark was on this route. John S. Harrison lived on the property and ran the stage stop.

By the 1850s, the competition among stage companies, called stage lines, was evident in the newspaper advertisements. Harrison advertised tri-weekly service from Austin to San Antonio by way of Manchac Springs, San Marcos, and Seguin. J. L. Allen ran a weekly stage line from San Antonio to Seguin, Gonzales, Victoria and Indianola for a fare of $12.50 for the entire trip.

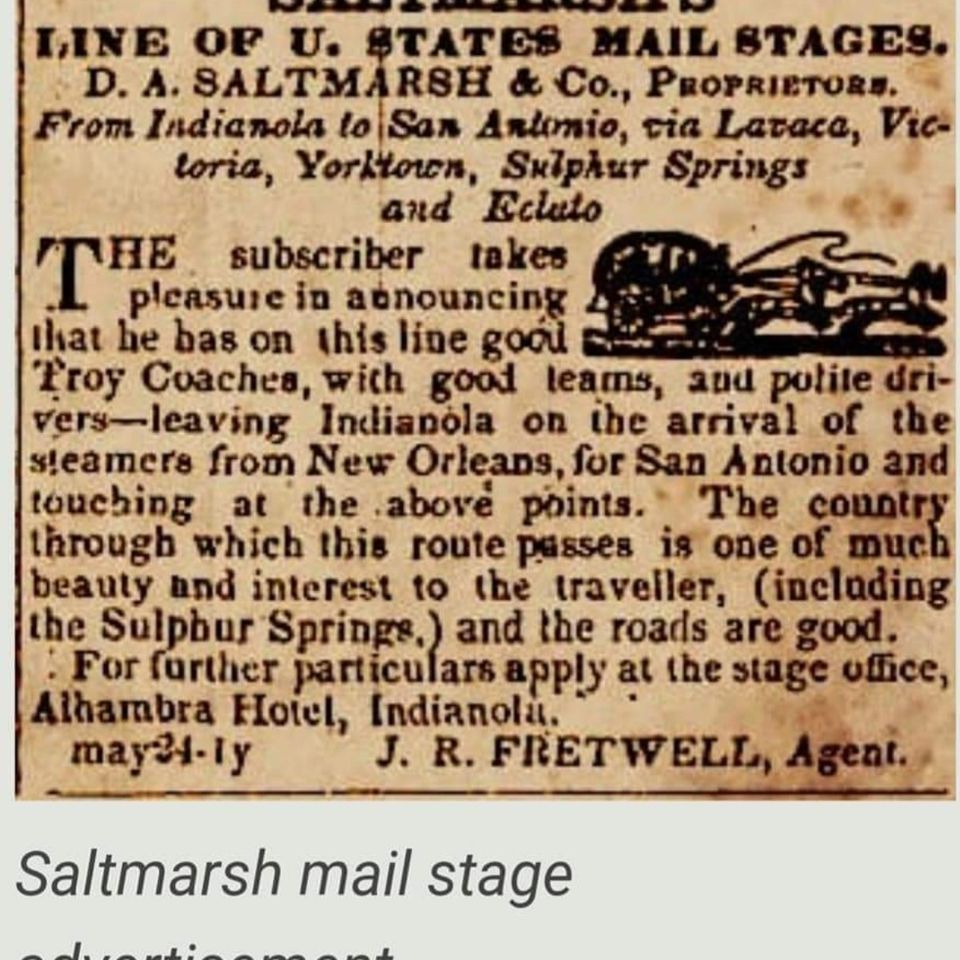

Then in 1851, an experienced Eastern stage operator opened a line from Port Lavaca and later Indianola to San Antonio. D.A. Saltmarsh and his brother, Orlando, were successful mail contractors and stage operators from the East Coast. The Galveston newspaper wrote about the arrival of their six Troy (built in Troy, NY) coaches in that city on their way to San Antonio. Saltmarsh's line ran from Indianola to San Antonio by way of Lavaca, Victoria, Yorktown, Sulphur Springs, and Eclato (Ecleto). In 1854, Saltmarsh purchased property on the old Gonzales Road in the area of Cottage Hill, eighteen miles east of San Antonio and established a stage stop on this route. Claiborne Rector was purported to have a stage stop on the old Gonzales road on this line in what is now La Vernia. John Sutherland, an experience stage stop operator also had a stop on the old Gonzales Road (renamed Sulphur Spring Road in 1848) at what is now Sutherland Springs on this route.

B. A. Risher of the Western Texas Stage Company in 1857 advertised a route that featured four-horse coaches connecting Indianola to Austin and San Antonio. The Indianola to San Antonio route ran three times a week through Lavaca, Victoria, Yorktown, and Sulphur Springs and boasted a travel time of forty-eight hours.

Twenty Mile House, located twenty miles east of San Antonio on the old Sulphur Springs Road between Cottage Hill and Post Oak (now La Vernia), provided pleasant accommodations, stables and forage for the travelling public. It was created by Henry Bowers and was later purchased and operated by San Antonio Alderman August (Gus) Sellingsloh.

John T. James, the first postmaster of Sebastopol (now a ghost town located between Floresville and Calaveras) and later the founder of Oakville, also operated a stage line. For a fare of $12.50, he transported passengers on his line of mail coaches from San Antonio to Lavaca through Helena, Victoria, and Goliad. It is interesting to note that many of the stage stop operators (James, Sutherland, Harrison and Rector) were also postmasters.

Stage operators, whose lines ran to Texas ports, had unique scheduling demands. Passengers travelling to Port Lavaca, Indianola, or Indian Point, often planned to continue on to Galveston or New Orleans by ship. The mail also arrived and departed on ships. The stage lines scheduled their arrivals and departures to coincide with the arrival and departures of these ships. Adding to the complexity of transport were the shallow draft ferries like the Yacht that were used to carry passengers and freight to and from the deep draft ships moored off shore. (Courtesy of Lost Texas Roads)