A.H. Polley tells how he turned the Western Trail...

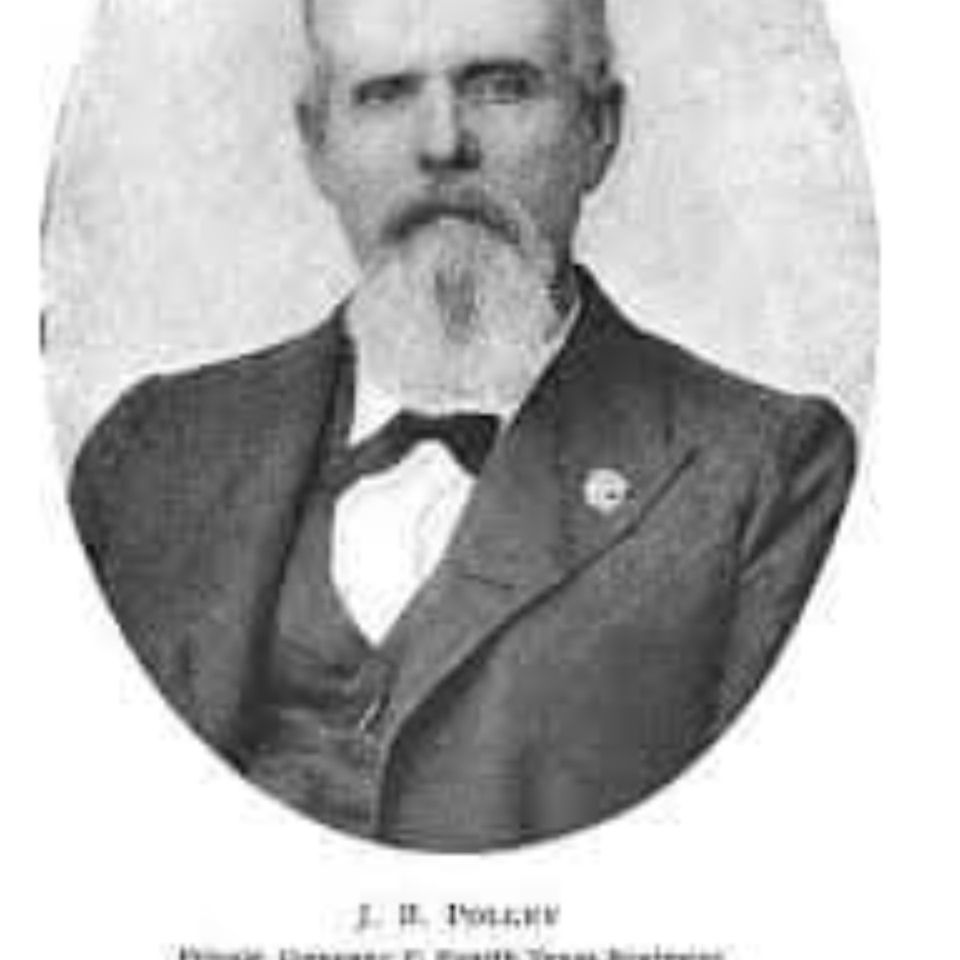

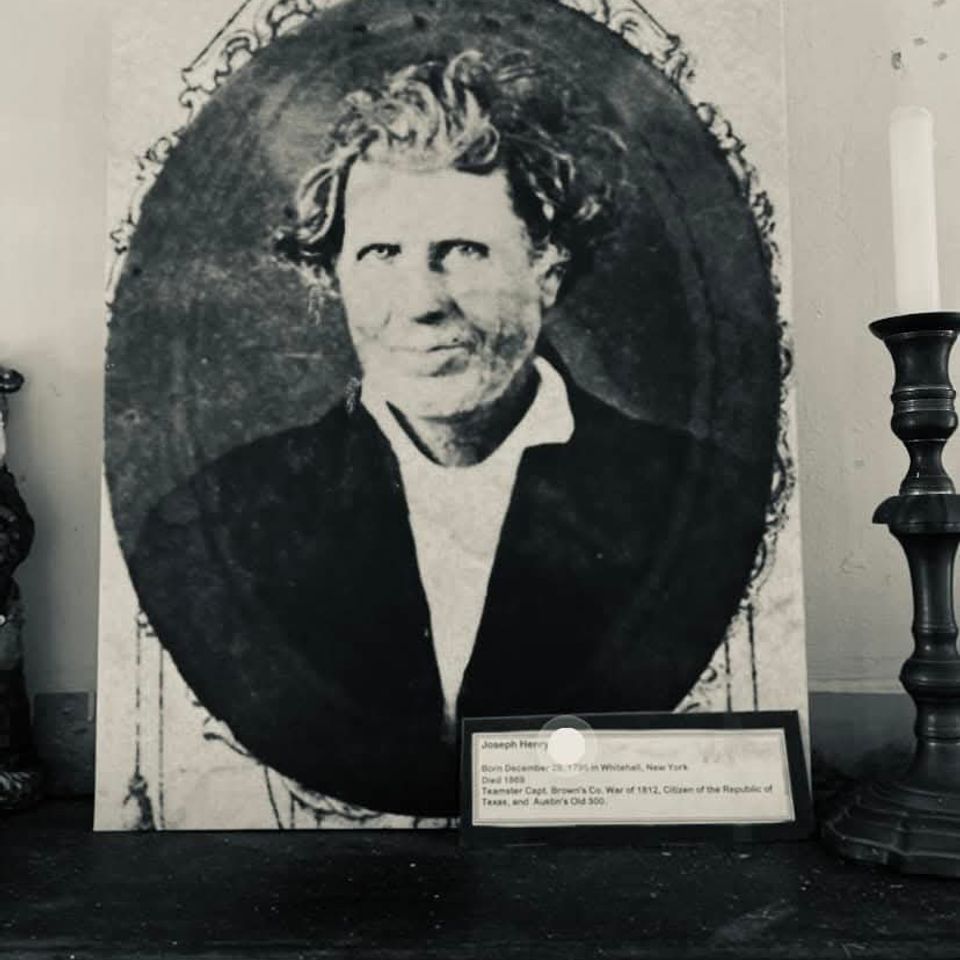

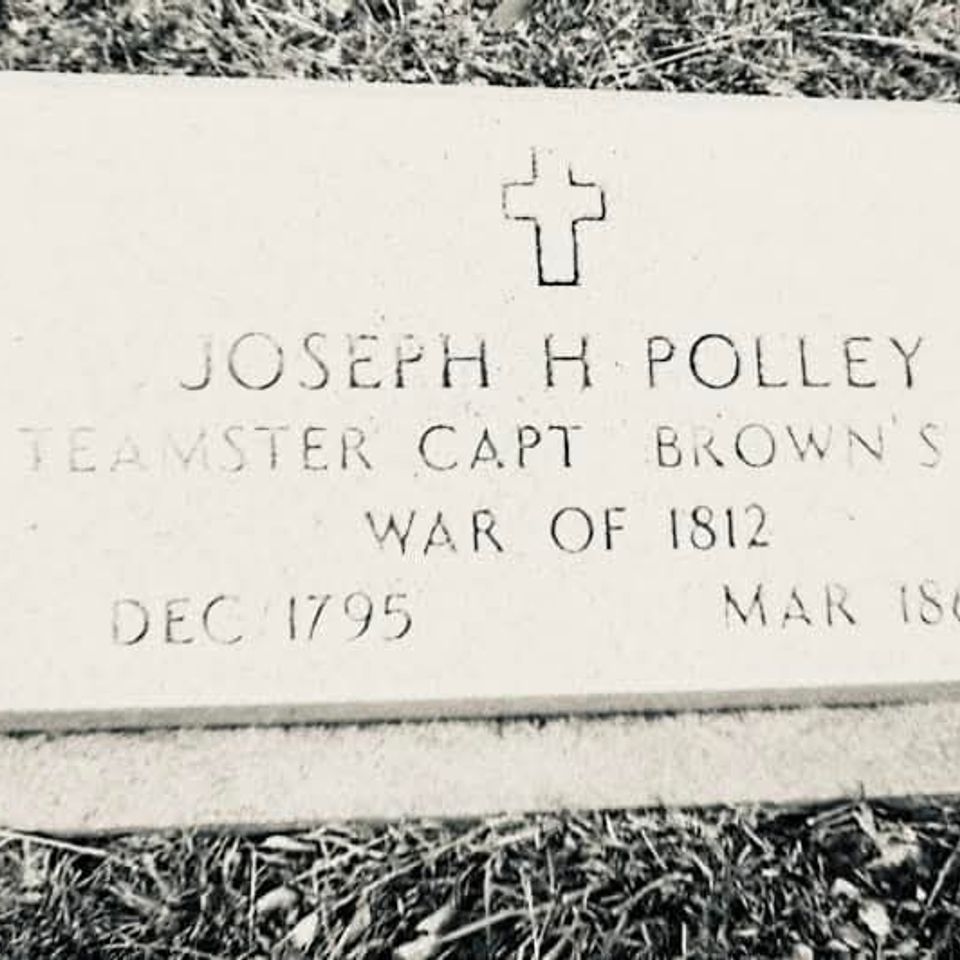

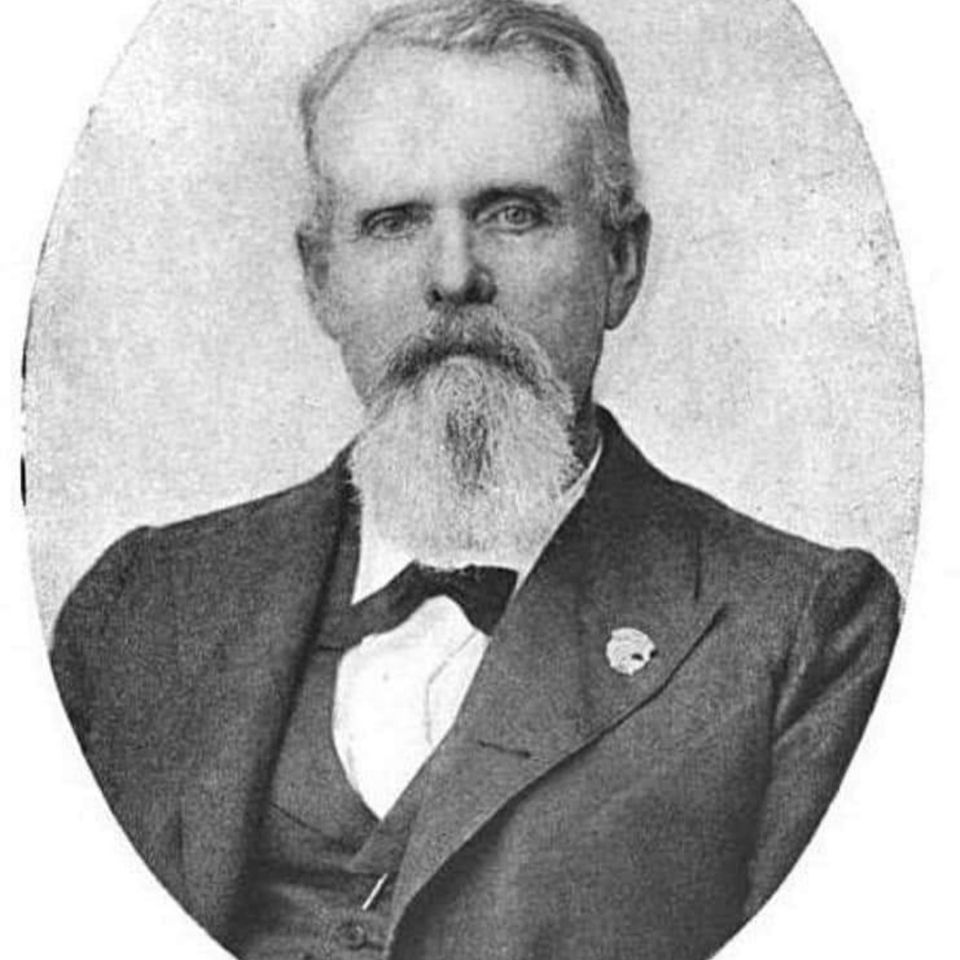

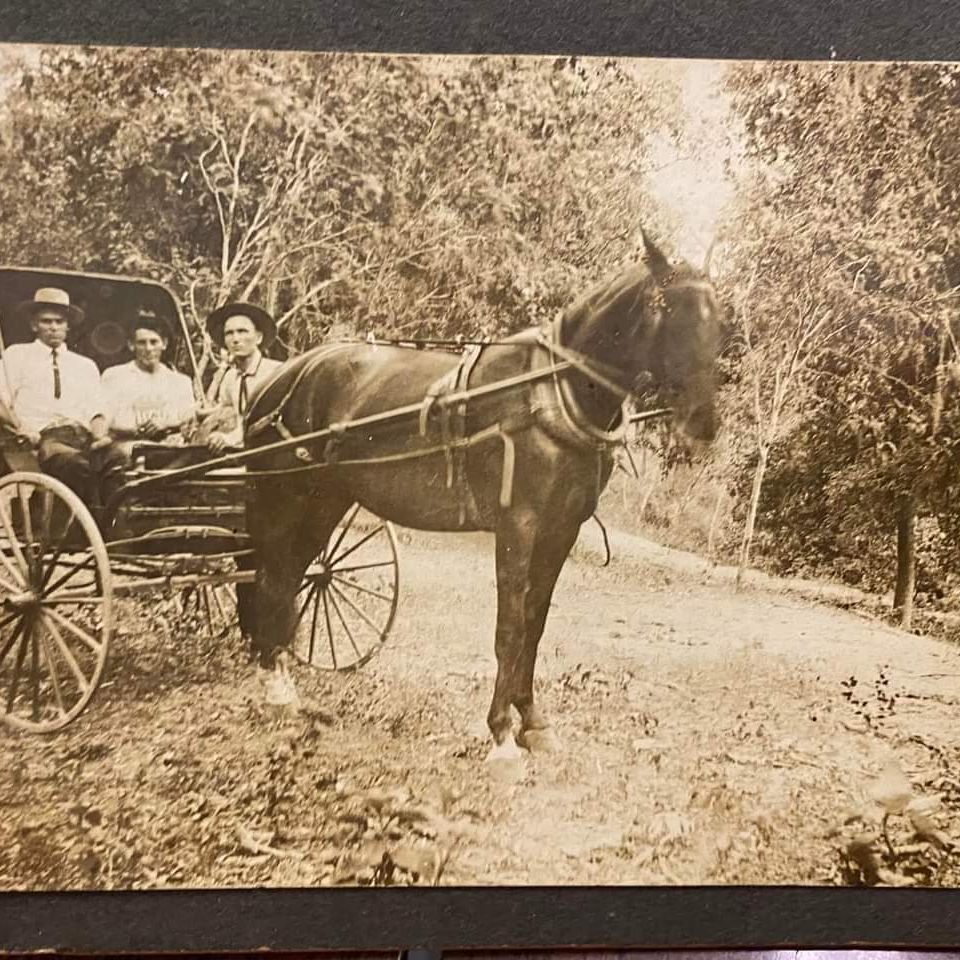

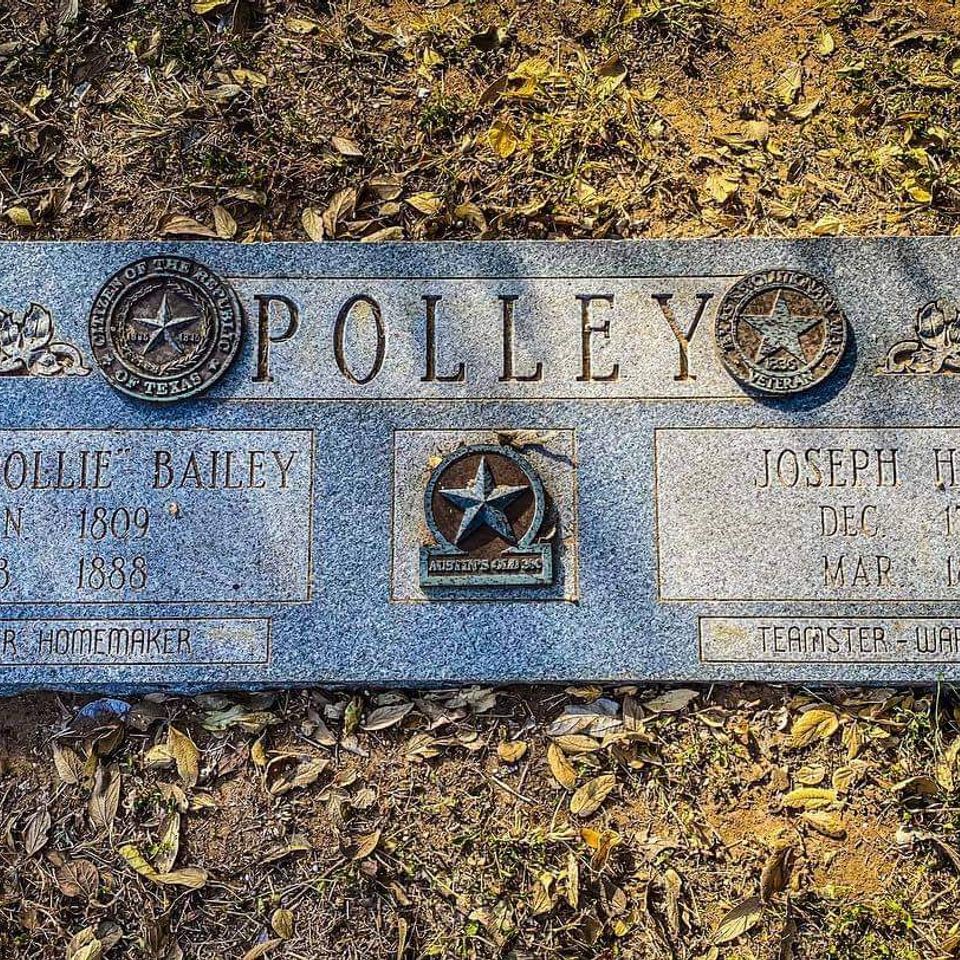

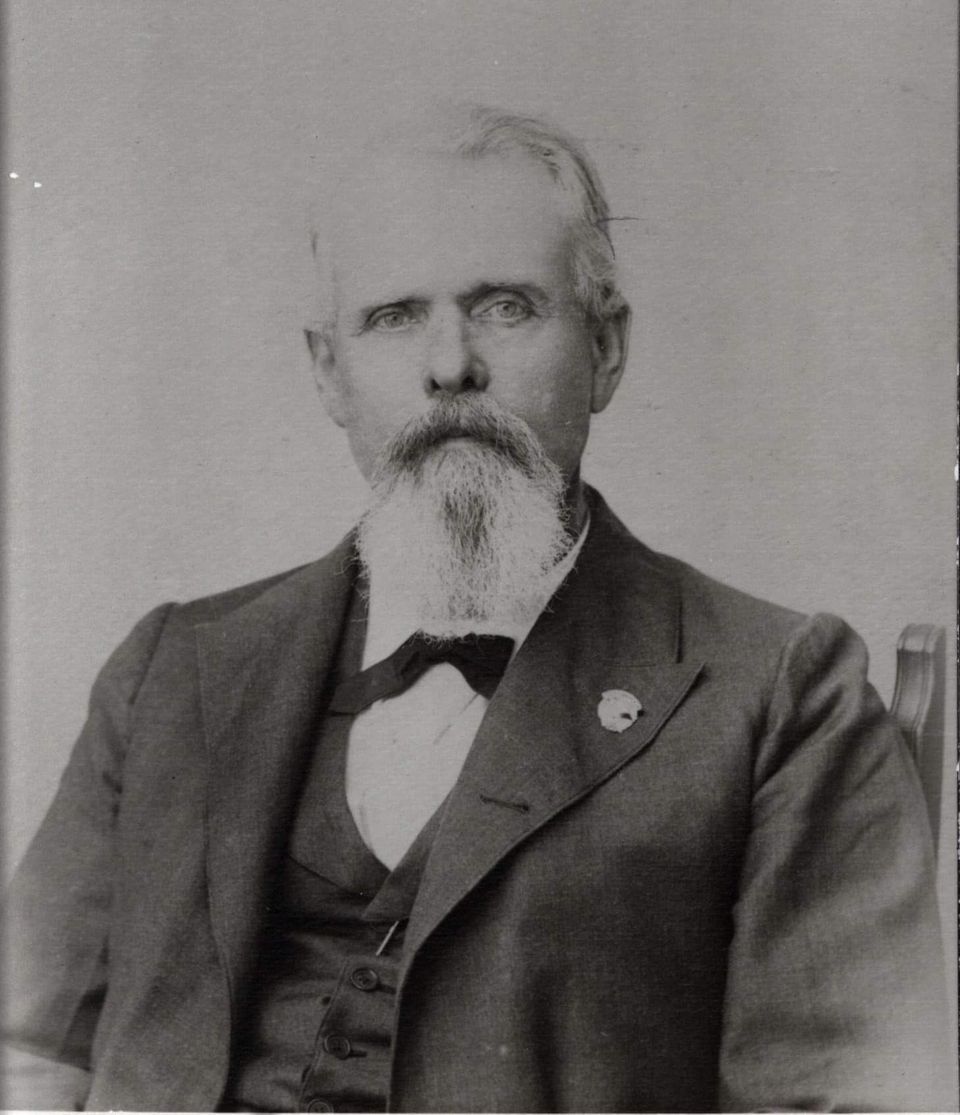

A. H. POLLEY, known the cattle world over as Hub Polley of Austin, Texas, talks as unconcernedly about the filibustering and colonization eras; the Texas revolution and establishment of the Republic, as of present affairs of State. And with reason; for Jean Lafitte's dare-deviltry in defying the embargo act the failure of Long's invasion, the freebooters, and smugglers infested coast regions, were as much discussed in his childhood home as are the latest scientific discoveries, or airplane records in our own today. And the name of Polley is inalienably allied with Texas independence from the first faint whisper to the victory on San Jacinto's battlefield.

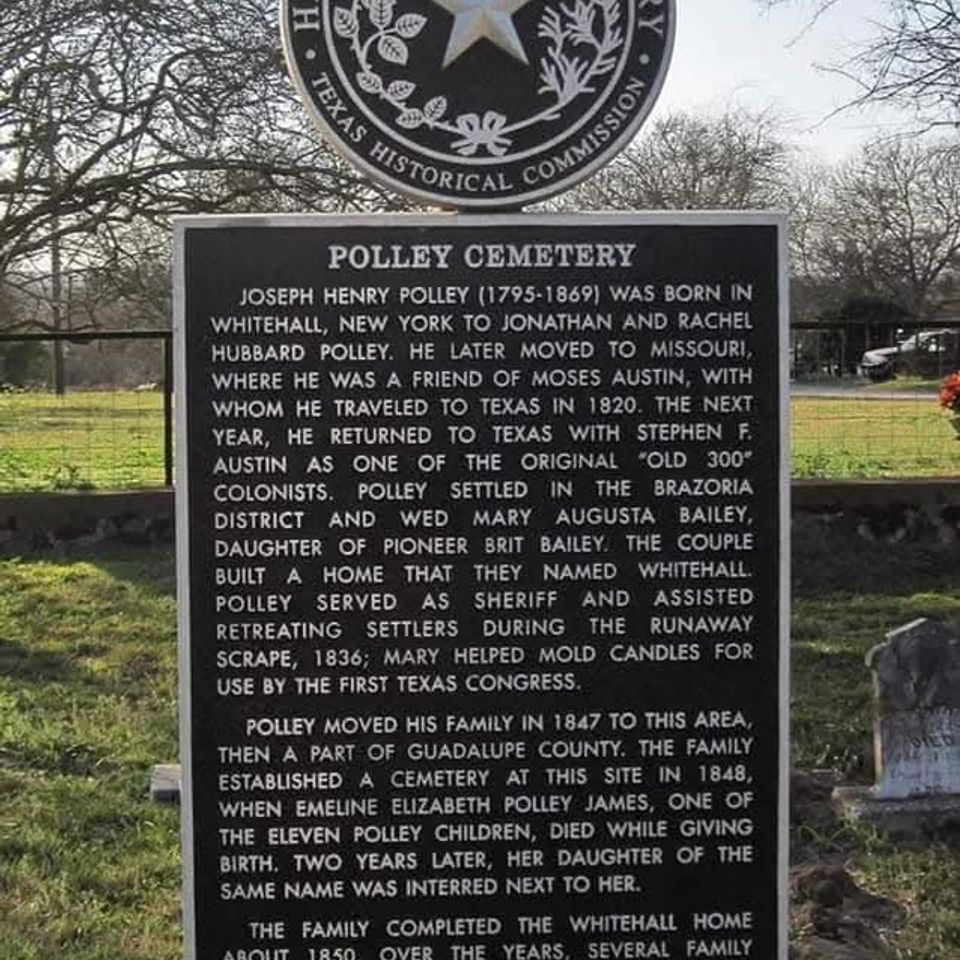

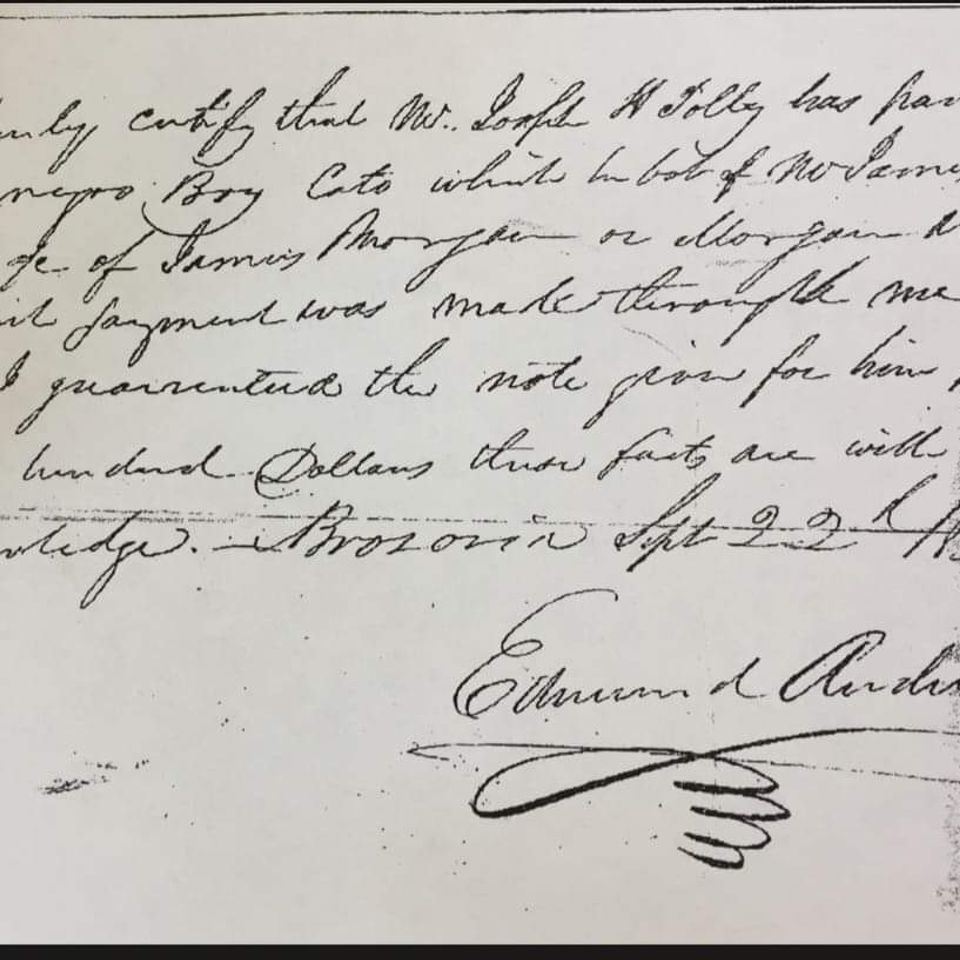

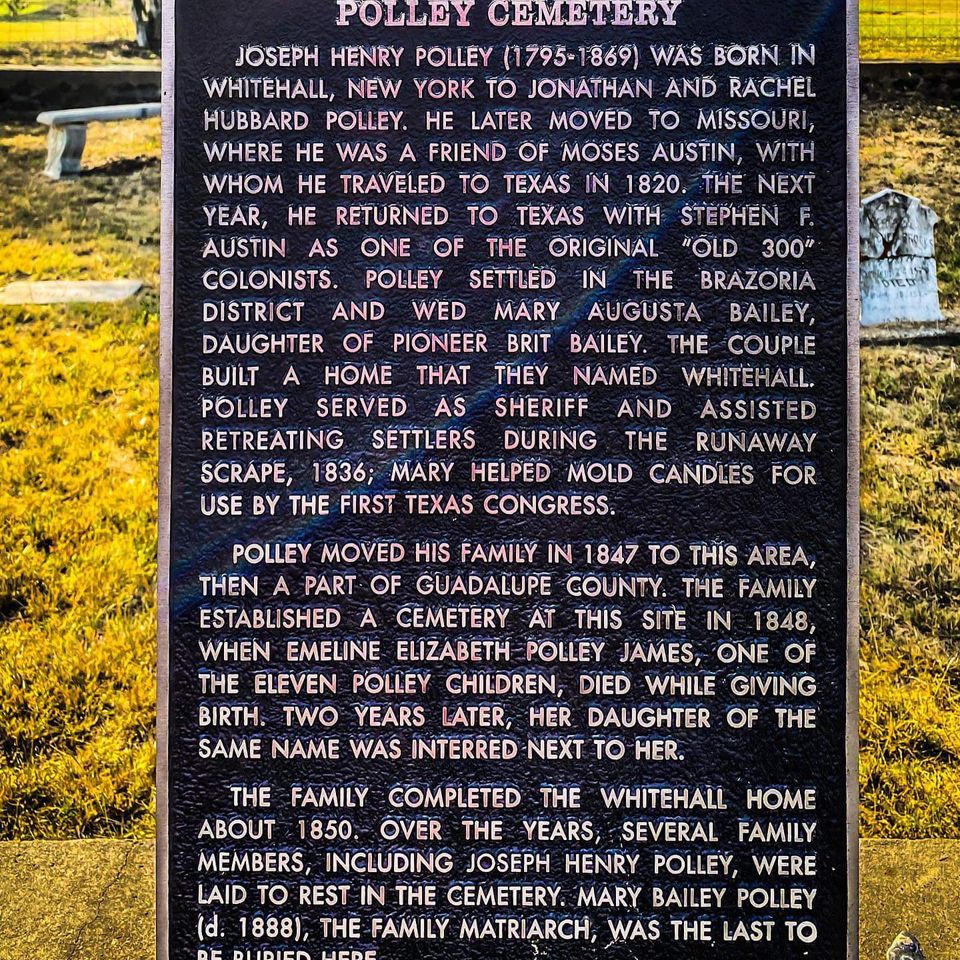

The parents of young Joe Polley had, upon learning that Moses Austin had made application for a colonization land grant from the Mexican Government in the province called Texas, resolved that when the time was ripe they would be among the first to make the journey. It was, therefore, with genuine regret that they learned of Austin's death, June 10, 1821. Not only for the loss of a man of outstanding qualities and character, but for the removal of such a signal leader. In addition to this was the personal discomforture entailed by the disarrangement of plans for participating in a novel journey and an adventurous undertaking, together with the relinquishment of the alluring prospect of acquiring land by reciting the colonist' s oath, the title to 640 acres of land, with an extra 160 acres for each child in the family and eighty for each slave brought for location.

But the scales turned the following August when word was conveyed to them by Stephen F. Austin, to hold themselves in readiness for colonization at an early date, for by intercession, on the part of one, Baron de Bastrop with Governor Martinez, the grant had been obtained and that it was his purpose to carry out, in detail, the plans of his beloved father. He, also, stated that the Mexican colonization law had so changed that the head of each colonist family would obtain 4,605 acres of land instead of the promised 640, with a settlement of 1,476 acres on every unmarried man, upon location. A further proviso accompanied it stating that owners of mills or other public utility buildings should receive additional acreage. Town lots upon which to erect business buildings were to be given and all taxation withheld for a period of six years.

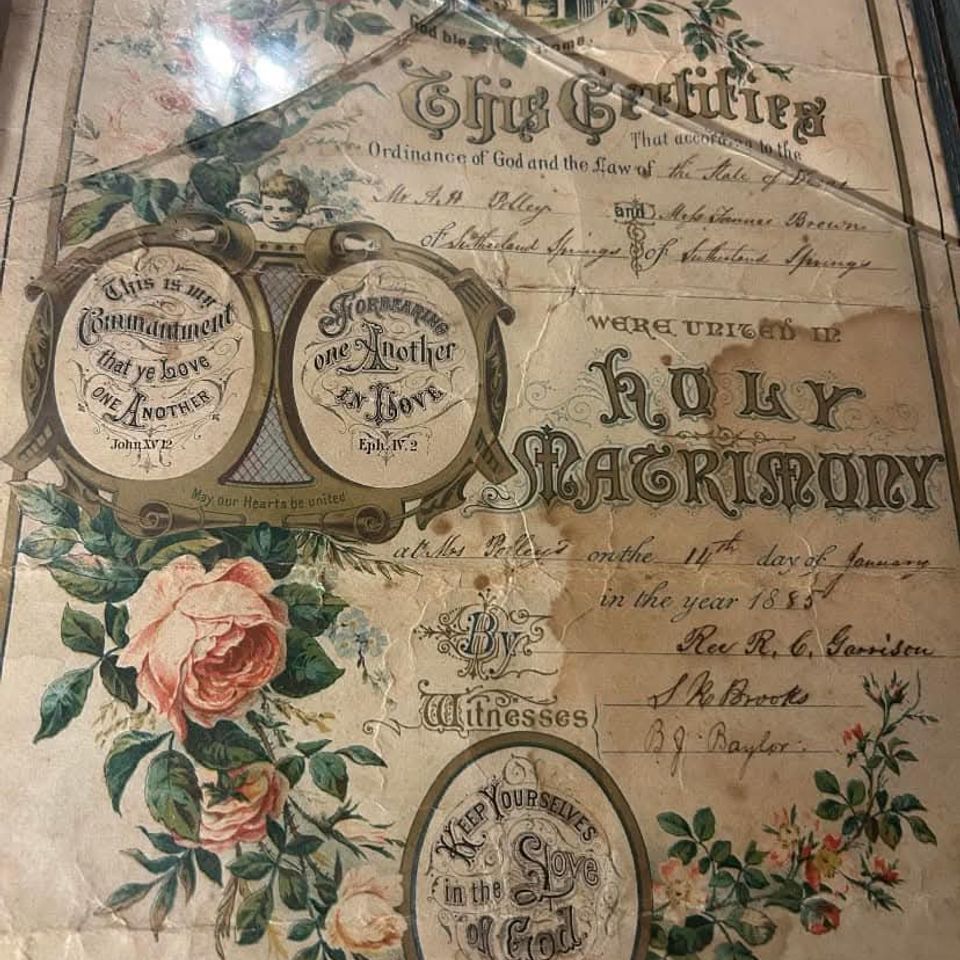

The grant selected by Austin, lay directly south of the San Antonio road, between the San Jacinto and Lavaca Rivers, a most productive and desirable area, which to reach involved a long and tiresome journey as those who made it could testify. But one that was teeming with interest, unusual situations and novel experiences. New babies were born en route, the train halting temporarily until the attendant physician smilingly announced to the joyful parents that they were now entitled to another 160 acres of Texas land. Marriages were solemnized, brides bedecked in orange blossoms and wedding veils; their dressing rooms covered wagons, the bridal altar nature's own, wayside greenery forming a pastoral setting and the violin bow singing across the strings to the soft thrum of banjo accompaniment, as the minister spoke the solemn, "I now pronounce you man and wife." And sorrow also walked along, as more than one new made grave gave silent testimony.

Having arrived at Austin's grant of ten leagues of land, young Joe's father was accorded a headright, while he must needs content himself with a single man's allotment. Right bravely did the colonists attack the frontier problems confronting them and with such combined and concentrated effort that twelve months of time showed a wonderful development.

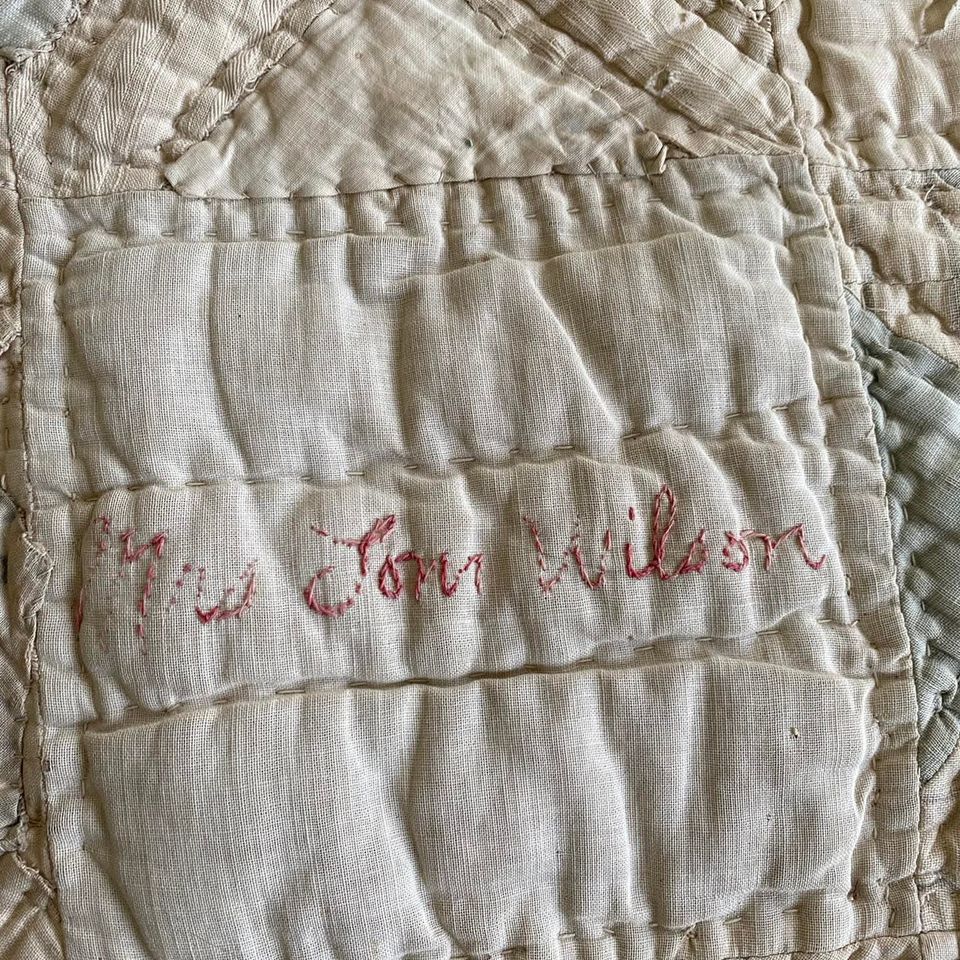

Early in the year of 1822 the parents of charming Mary Bailey, who later was wooed and won by young Joseph Polley, joined the group of colonists. To Mr. Bailey was also given a headright, in the assignment of which a mistake was made and Austin having assured himself that such was the case, sent a letter to Bailey stating it would be necessary for him to move to another tract. That letter, today, occupies a prominent place in the historical annals of Texas, framed as it is and hung on the bloodstained walls of the Alamo.

In April of that year, Austin having successfully established a goodly number of his required 300 colonists, took occasion to report to officials in San Antonio; whereupon he was informed that because of an unexpected revolution in Mexico it was necessary for him to go to Mexico City and ascertain his exact power of control in the colony and also to obtain a renewal of his grant. A most disconcerting requirement, coming at a very inopportune time, for new colonists were daily expected by boat and it seemed absolutely essential that he be on the ground to receive and locate them. But, realizing the necessity for expediency, he appointed Josiah Bell, a recent colonist, to supervise in his absence, of supposedly a month or so. He was astonished upon arriving in Mexico City, to find the country in such a state of upheaval that a stay of more than a year was required for the consummation of his business. But he left with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel to command militia and make war against all Indians attacking the colony. A wise provision, since in his absence the expected shiploads of settlers having arrived, with no definite instruction as to specific location, had camped temporarily on the Colorado River, only to be attacked and robbed of all their stores by the Carancahus Indians. This raid had occasioned such fear and dissatisfaction that many of the colonists had moved to other locations. But with Austin's return they came hurrying back. New settlers arrived and notwithstanding that from 1821 to 1824 Mexico was ruled by four different kinds of government, the 300 families required to make the Austin grant safe were successfully located before 1825.

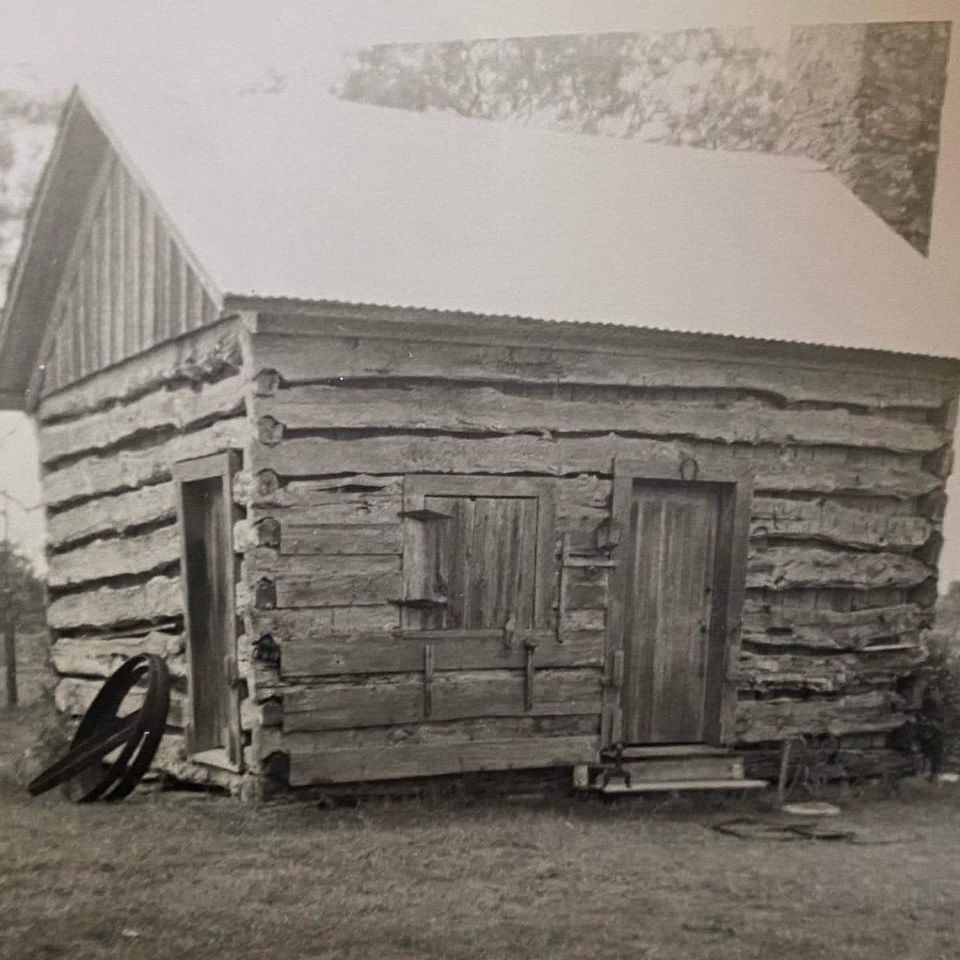

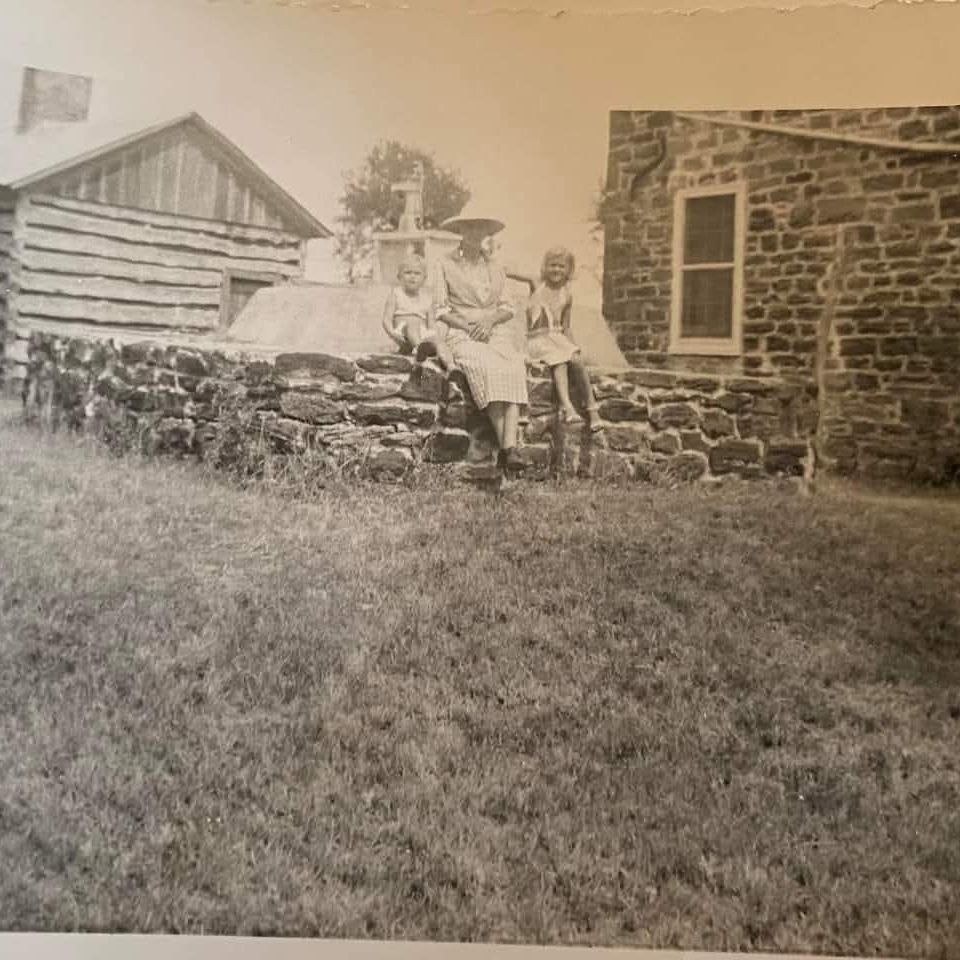

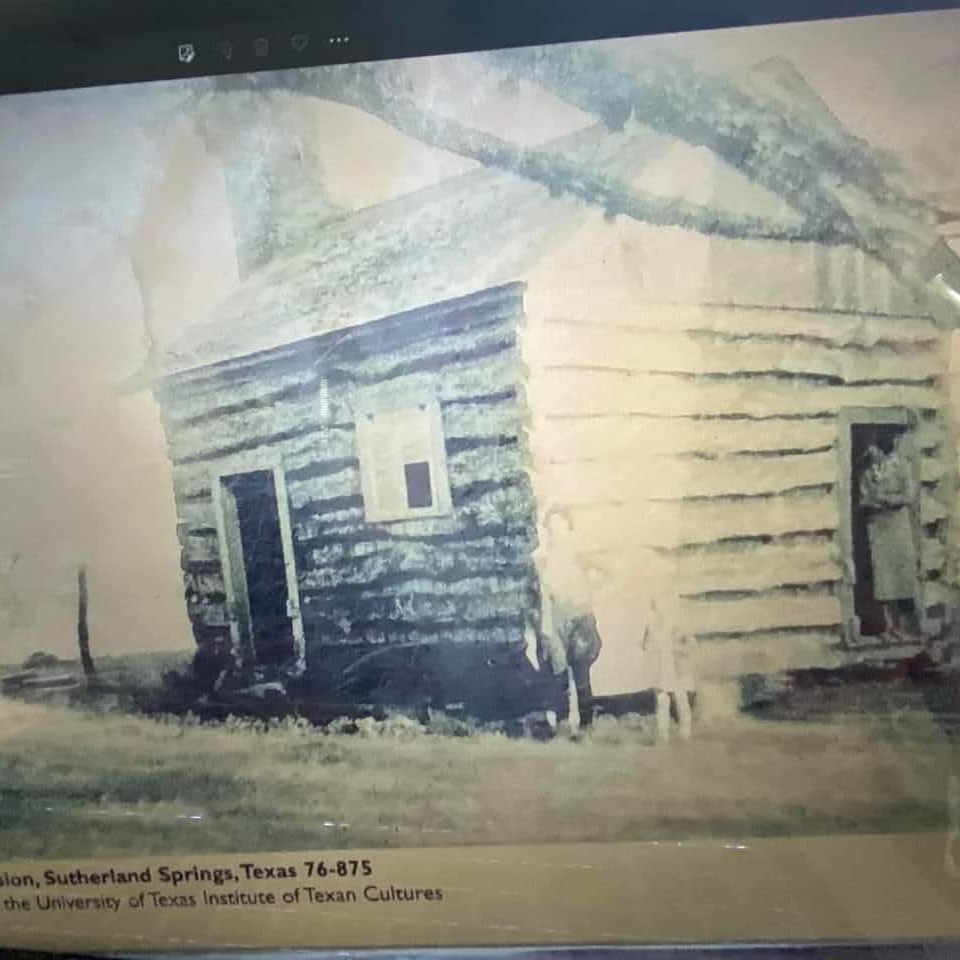

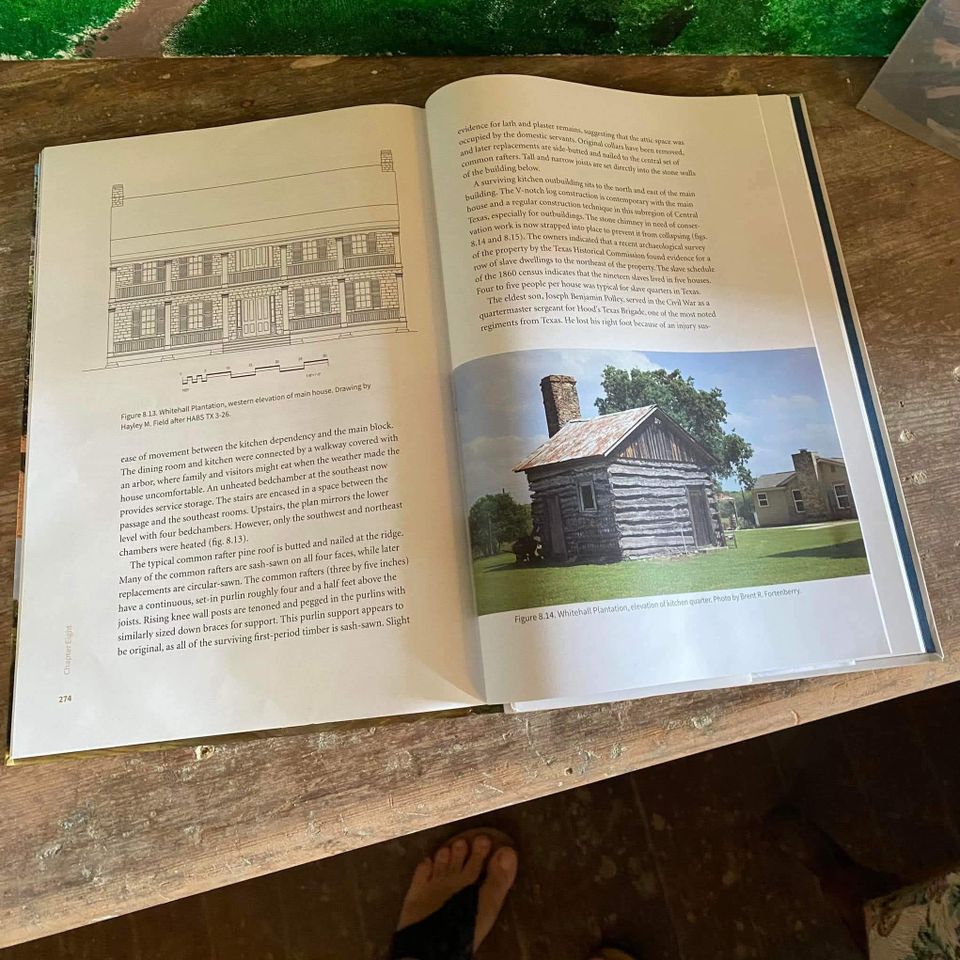

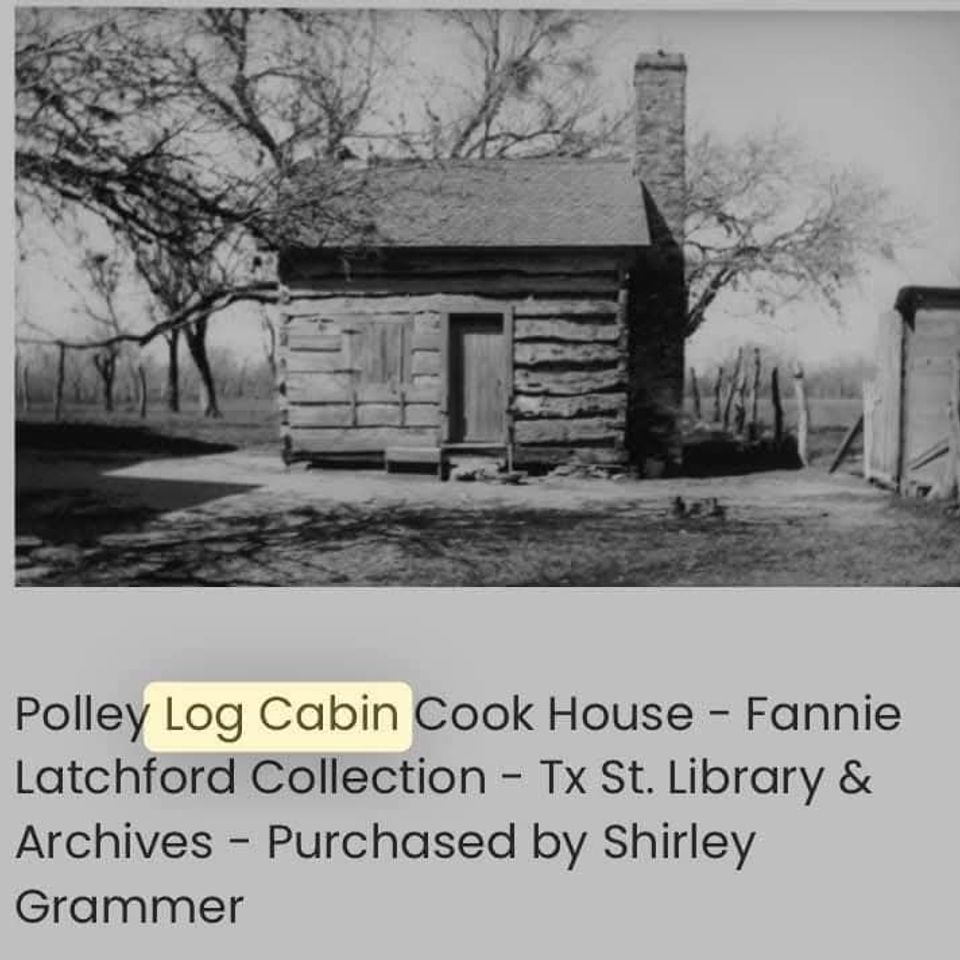

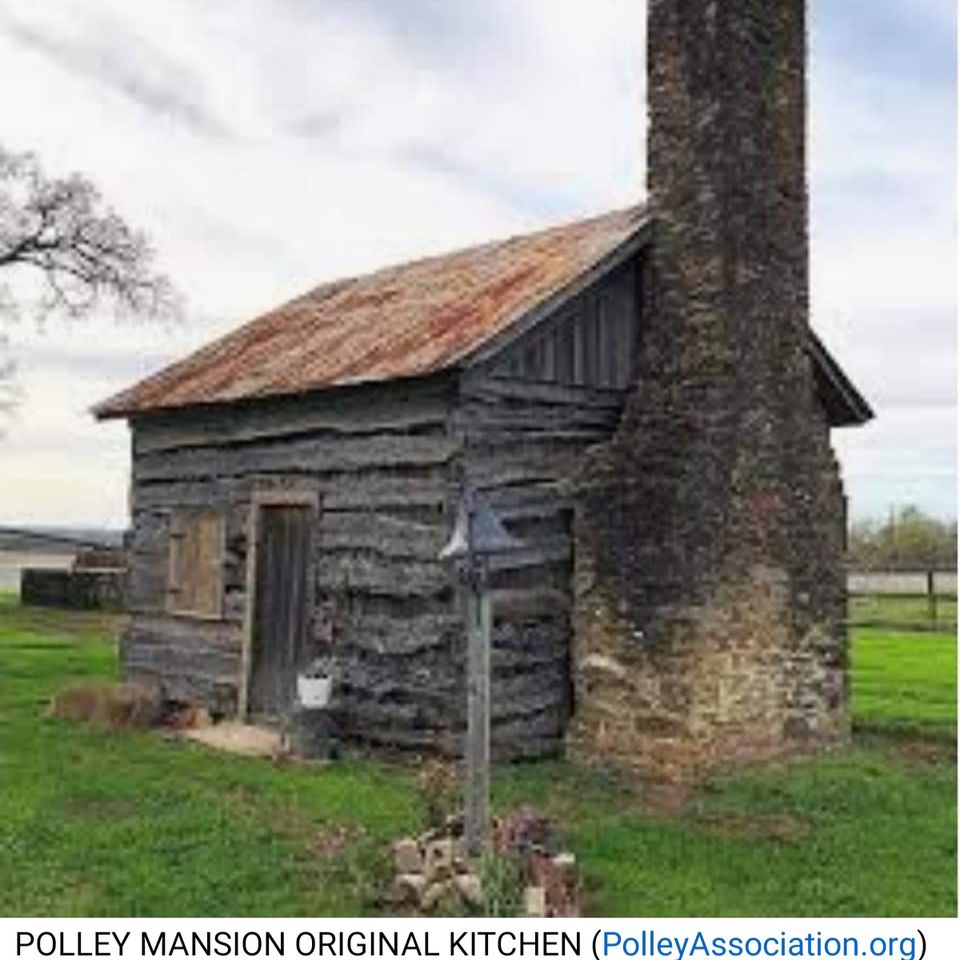

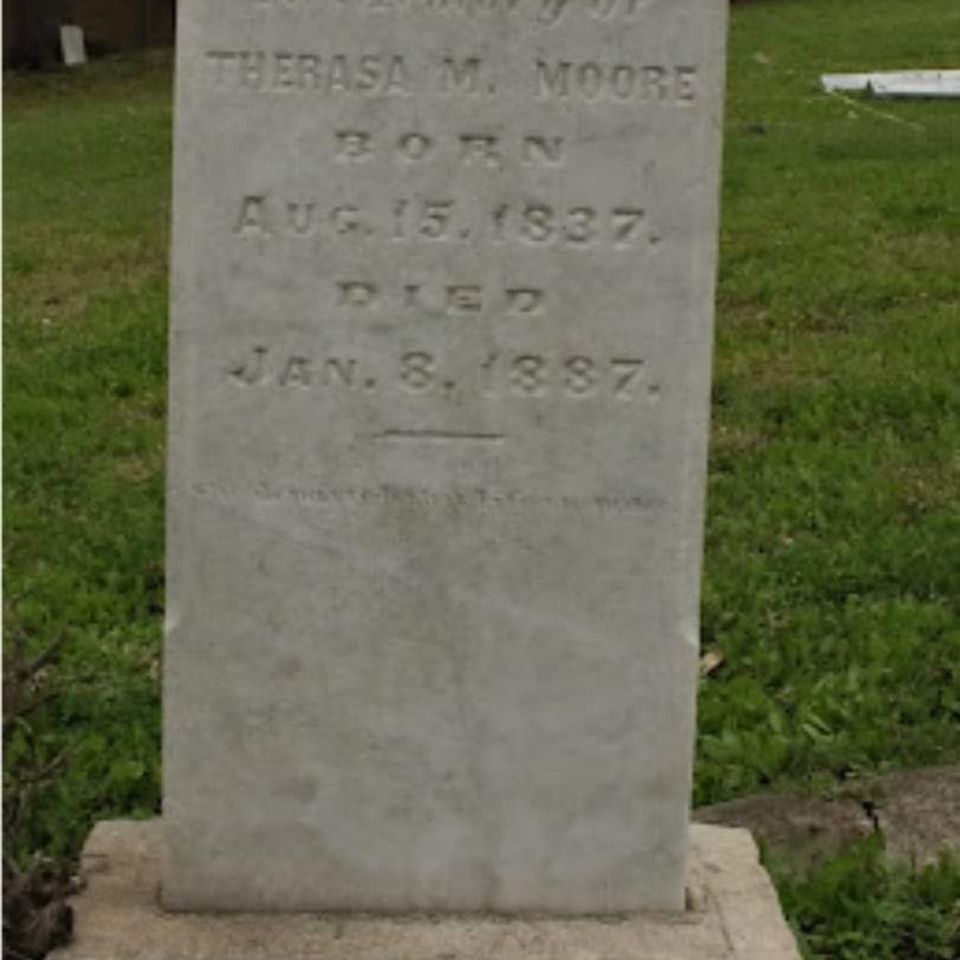

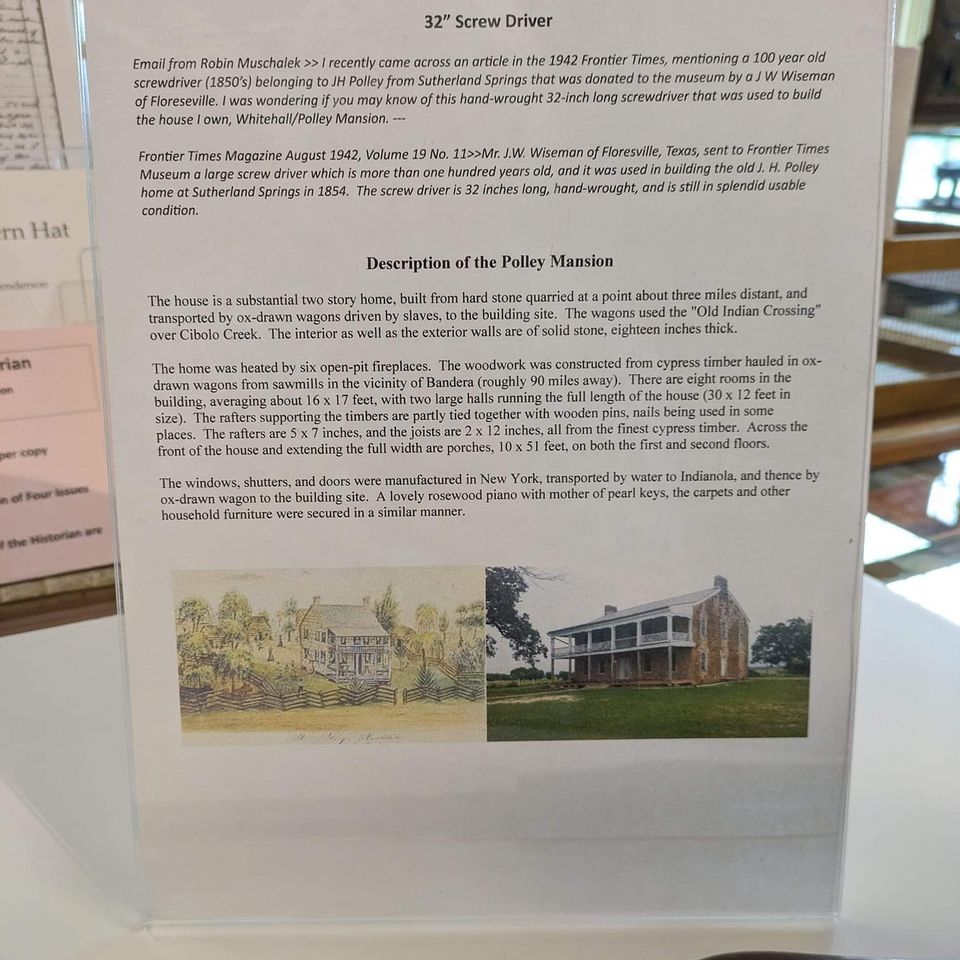

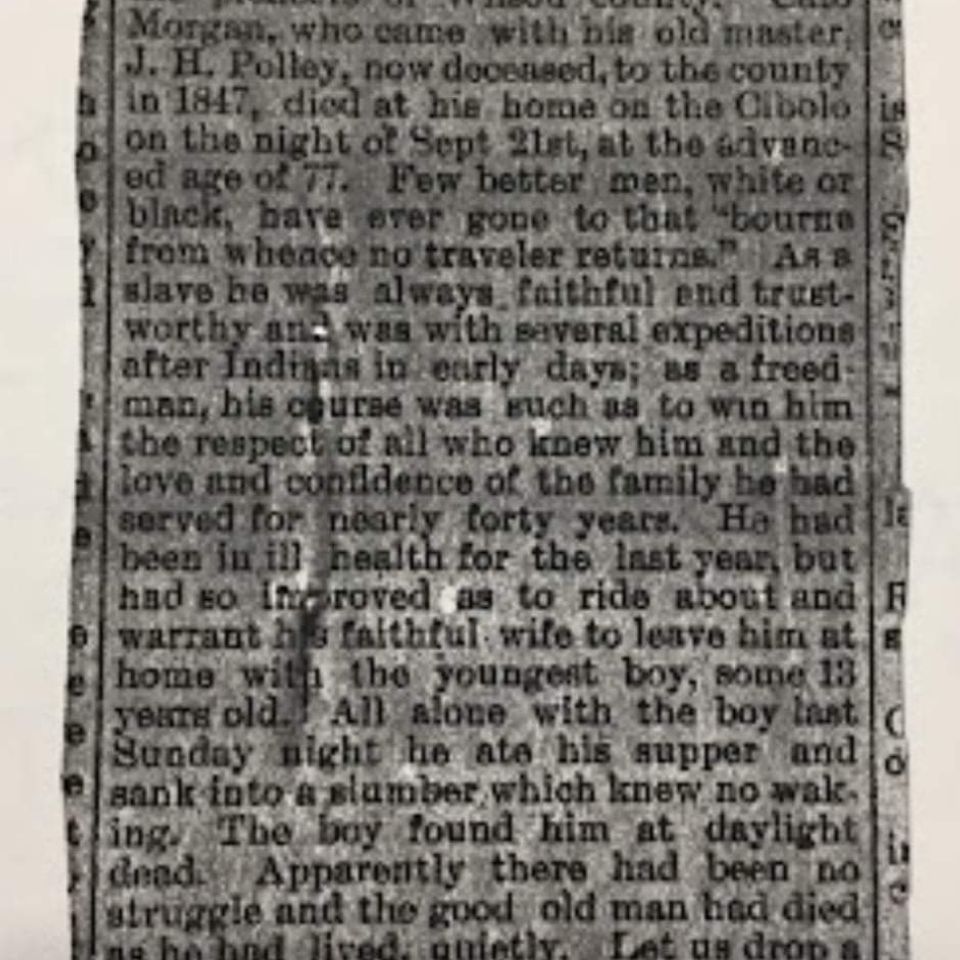

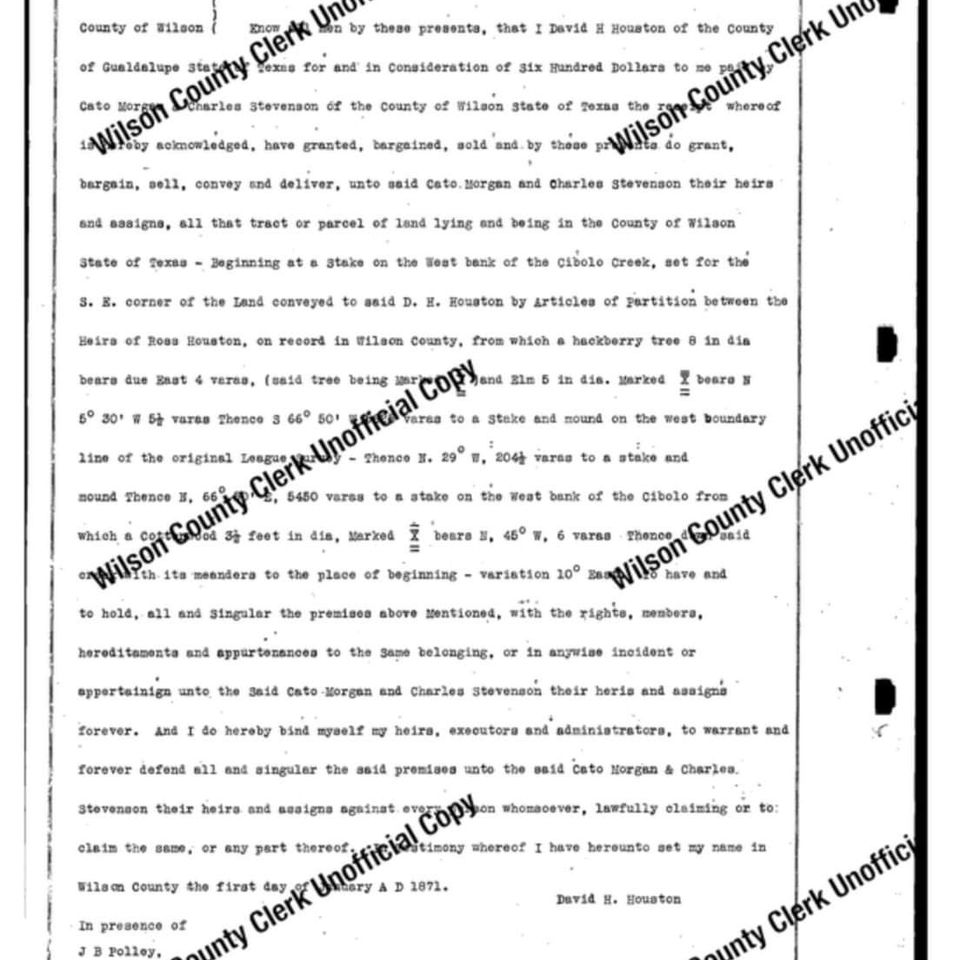

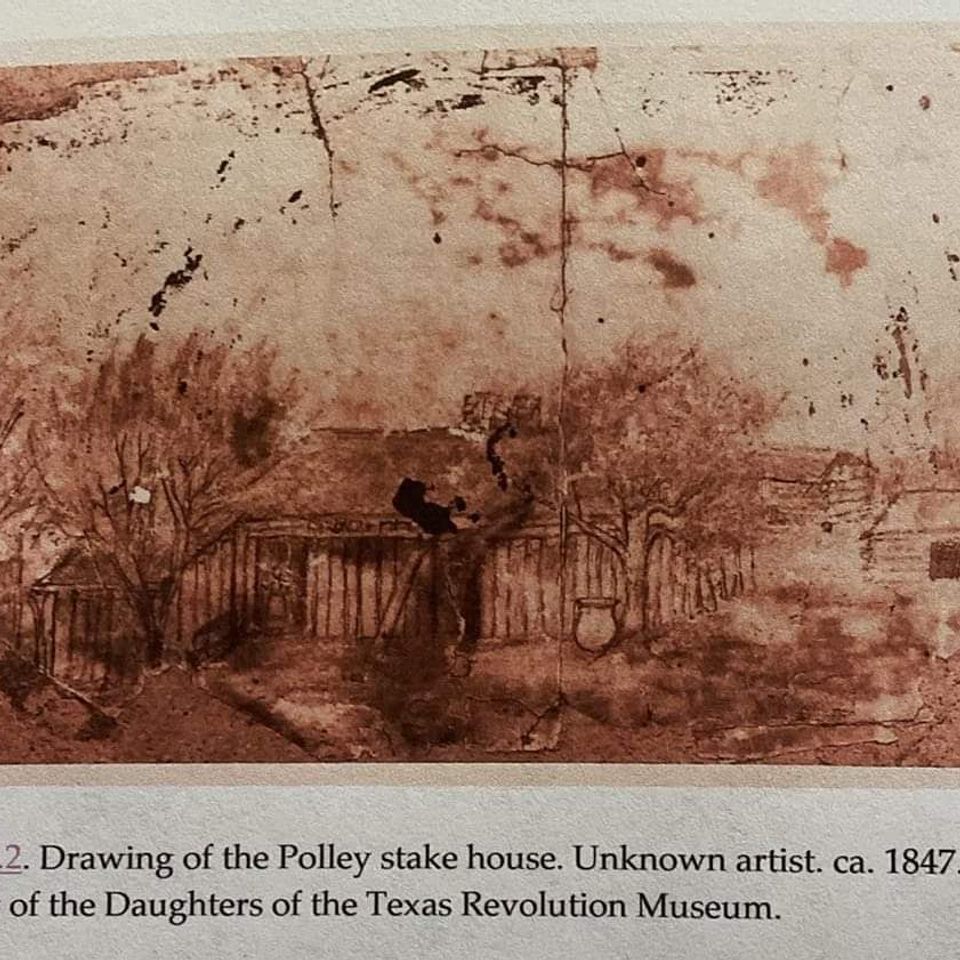

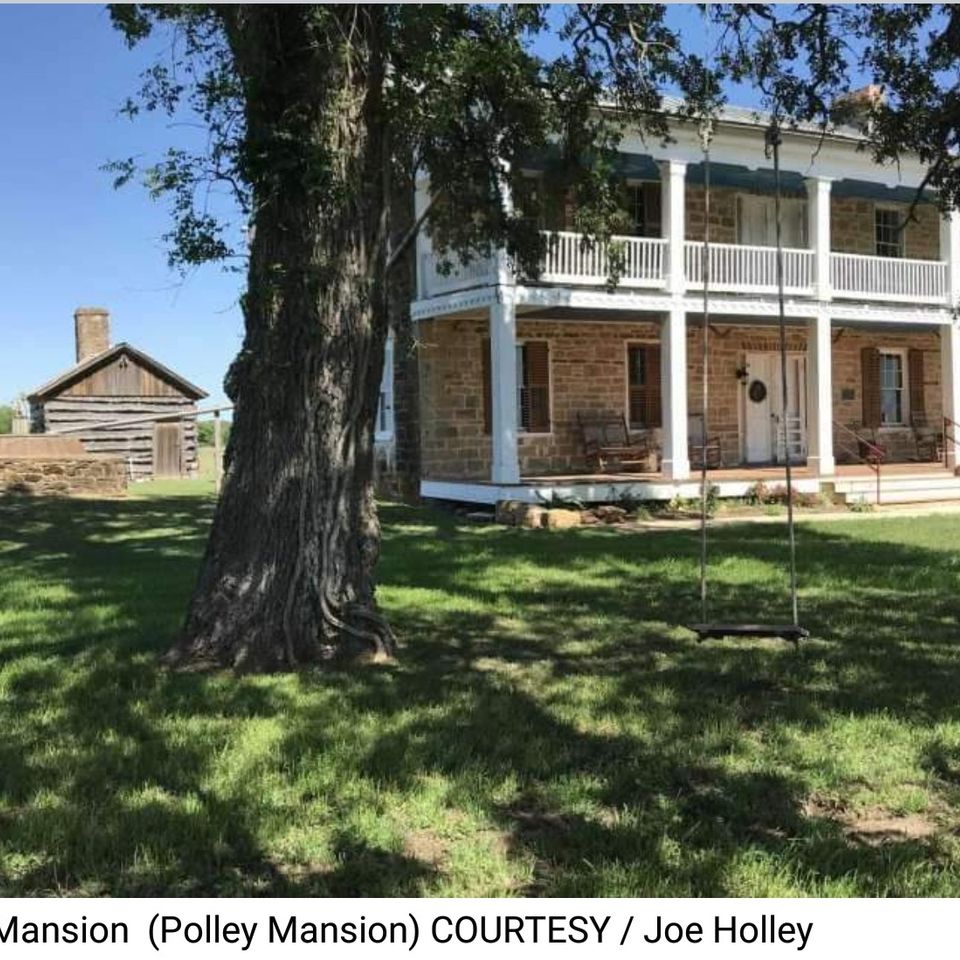

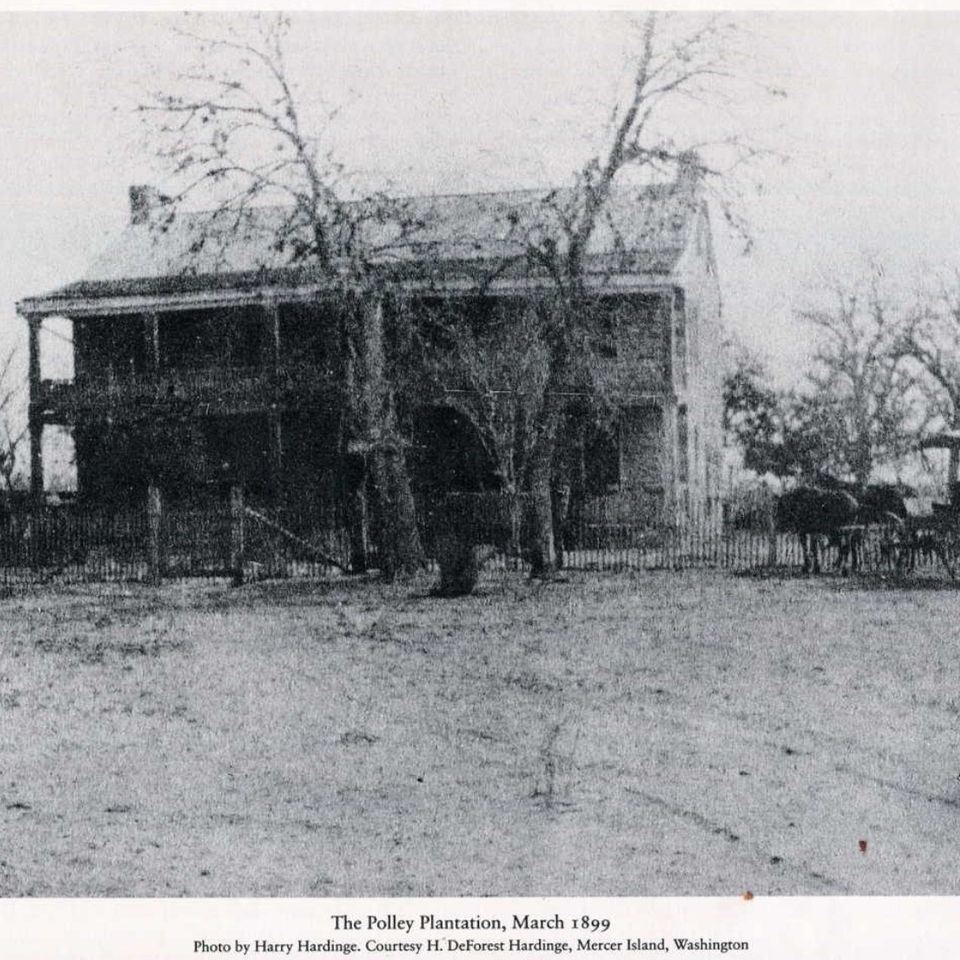

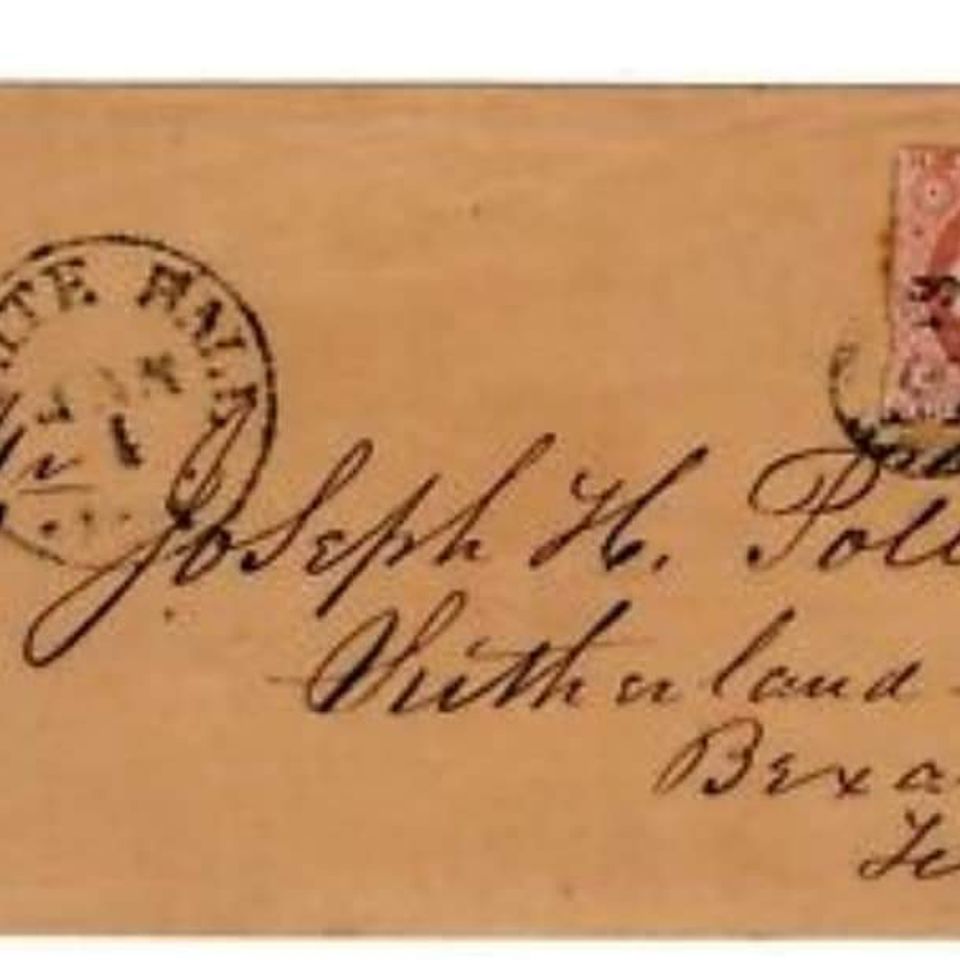

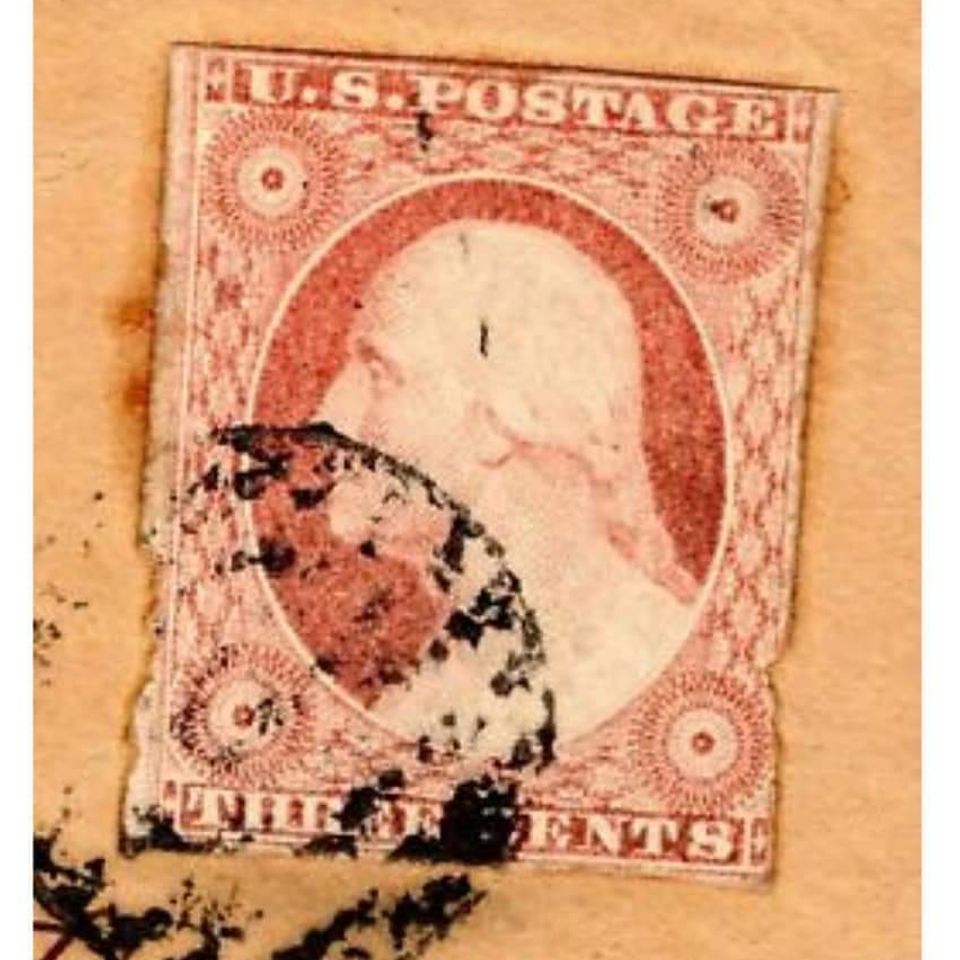

"But there were two of the colonists upon whom neither revolutions nor mutinies registered any effect, Joseph H. and Mary Bailey Polley. Too joyously happy were they in their newfound married life to give time, or ear, to matters of discontent, and thus did they remain on their colony claim until 1847, when, with their little ones, they moved from Brazoria County down on the Cibola Creek, thirty miles cast of San Antonio, where they founded and stocked a large ranch with 1,500 cattle. It would have been a somewhat difficult task to have outlined the grazing limits, since the creek was the dividing line between Bexar and Guadalupe Counties, governed by the law of the open range, with the nearest neighbor twenty miles away. The town of Sutherland Springs was then unborn and it was a wild land. The West was filled with dangers on every hand.

"Soon after my father moved to the Cibola, a man moved in and built a sort of rock fort, as a protection from Indians, who were riding every full moon and watching their chance for deviltry at all times. I was just a little shaver at the time so what I tell you of redskins will naturally be disconnected and the things that most impressed me at the time they occurred. The first of these was when the Indians stole every horse and mule father had, leaving him no alternative but to herd his cattle on the open range on foot, until he could buy more. Not an easy job in a new country with so few people, but the loss was scarcely considered by my parents, since we were left unharmed.

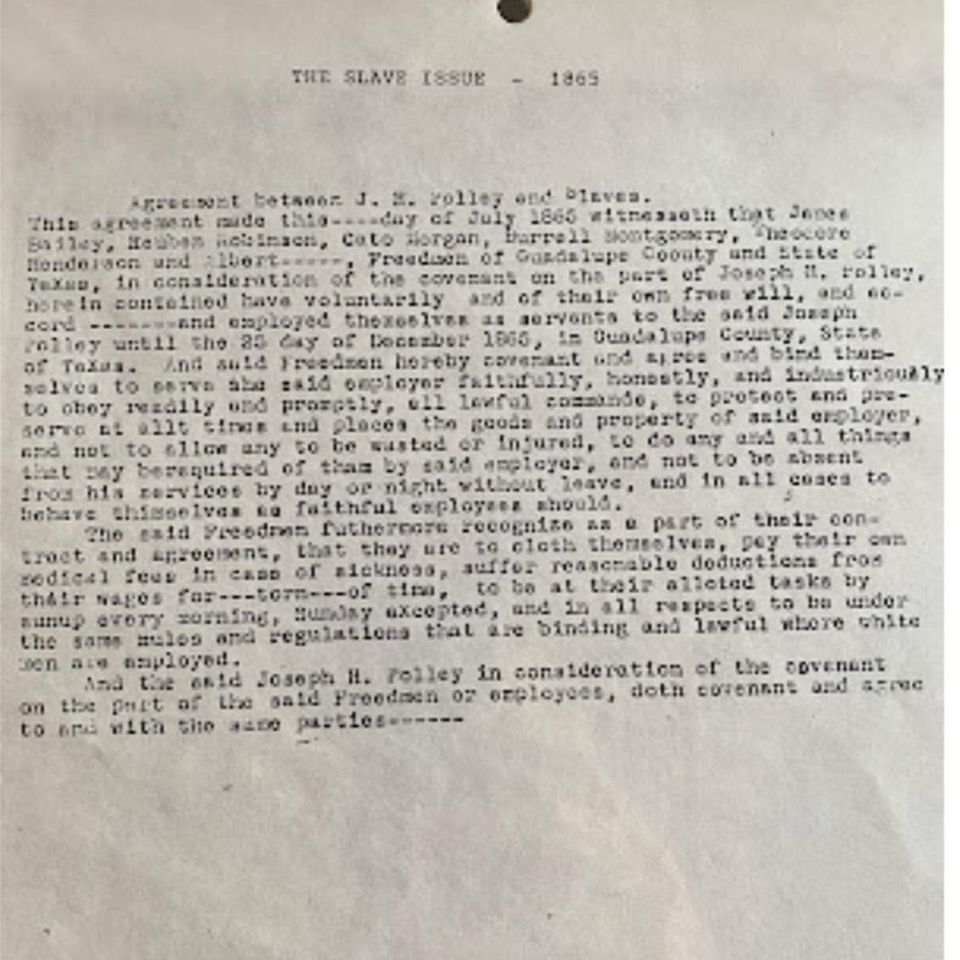

"Shortly after the raid a young man came galloping up on a beautiful white horse, its shoulders and flanks dripping with blood from his constant spurring to outdistance the Indians in pursuit and who must have been so few in number that they were afraid to follow him to the house and risk an outnumbered fight. The blacks washed the blood off, fed, curried, watered and rubbed the animal, then made him a good bed on which to rest when he had finished eating. I was highly interested in those proceedings and even more so I listening to their conversation about what they would do in such a predicament, never dreaming they would soon have an opportunity of proving it.

"An immense mustang grape grew within a few hundred yards of our house and when the grapes began to ripen mother sent two of our negro men to gather them so she could preserve and make jelly of them. While they were busy at this some Indians slipped up on them and got between them and the house. They jumped on their horses but could not get anywhere, for a dash either direction found the redskins right after them. Each of them carried what was called a machete, a big long knife, and one of them pulled his and made a run for the house. Strange to say, the Indians did not attempt to kill him, preferring, I suppose, to take him alive, which they did by roping him. While this was in progress the other one, who was riding a faster horse, dashed up the creek, crossed it and made it home. We never knew what happened to the man they captured but when mother sent again for grapes a well-armed guard went along to protect the pickers.

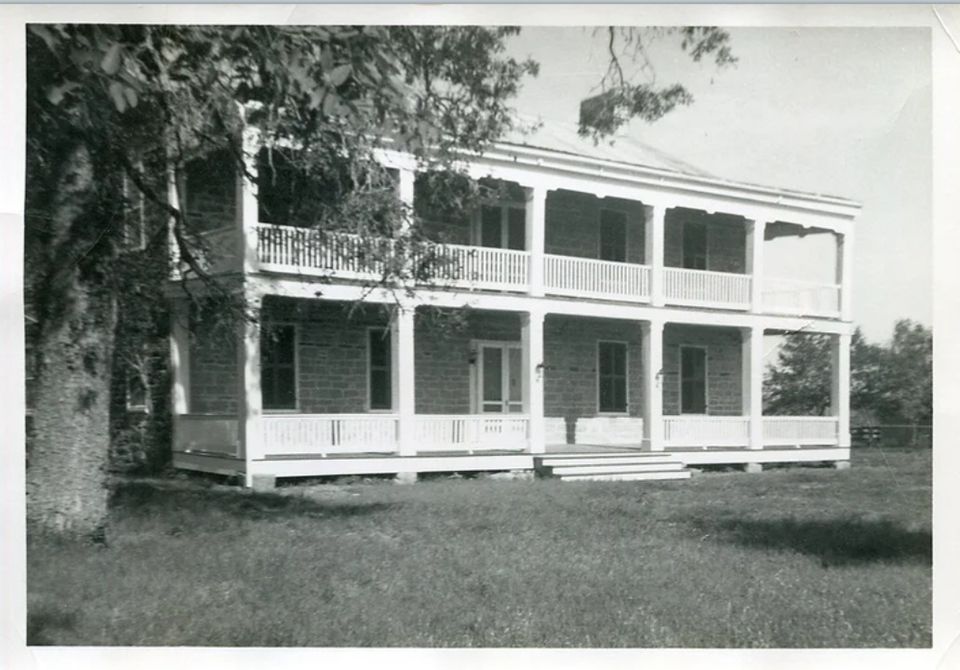

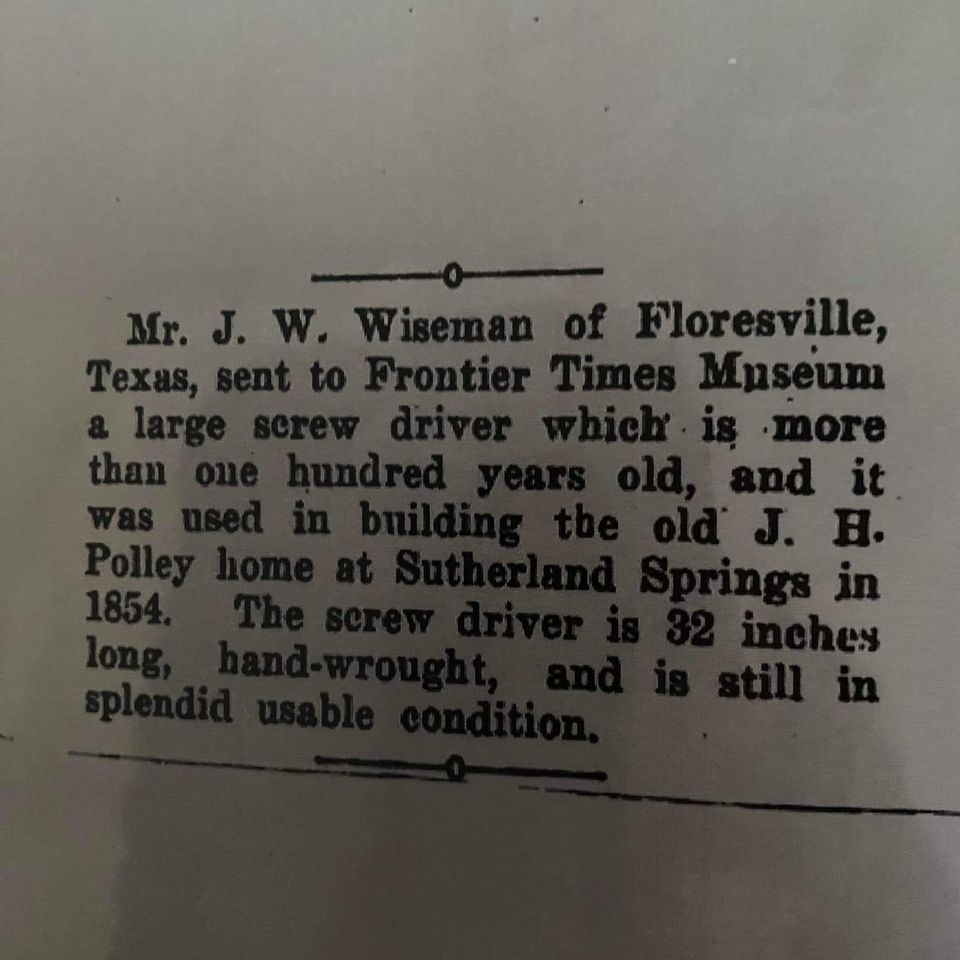

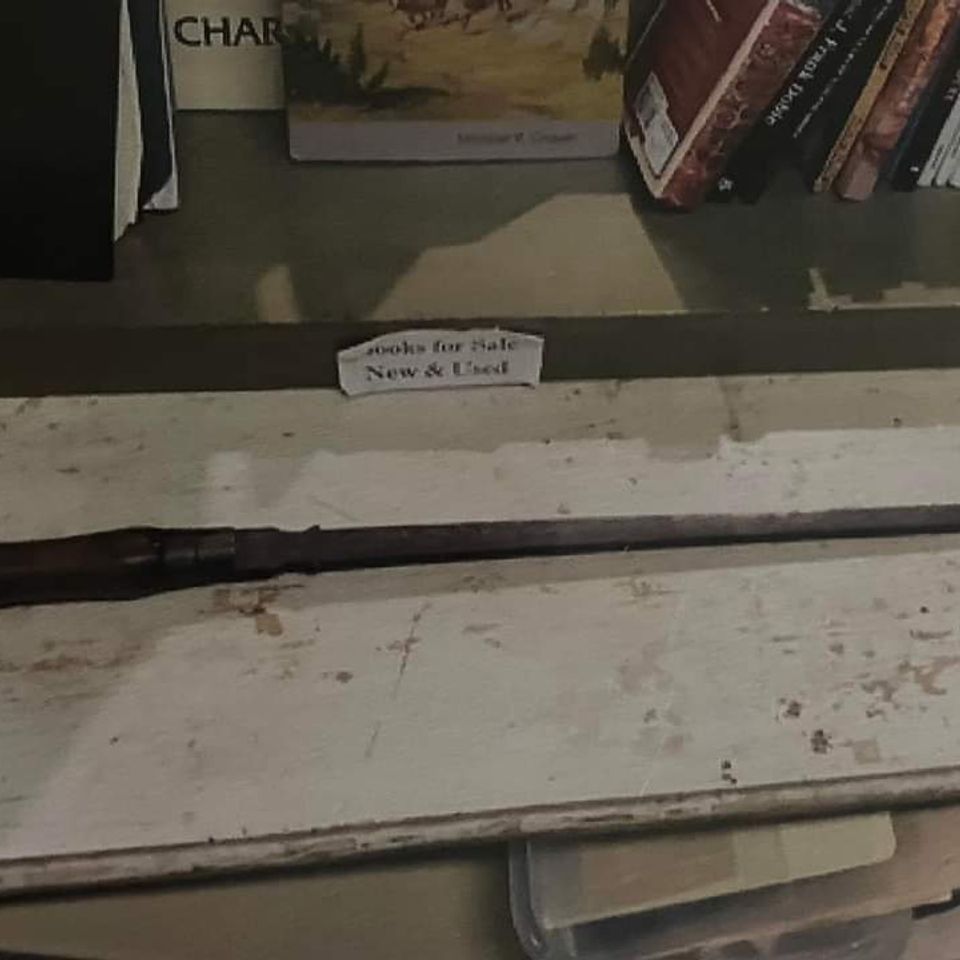

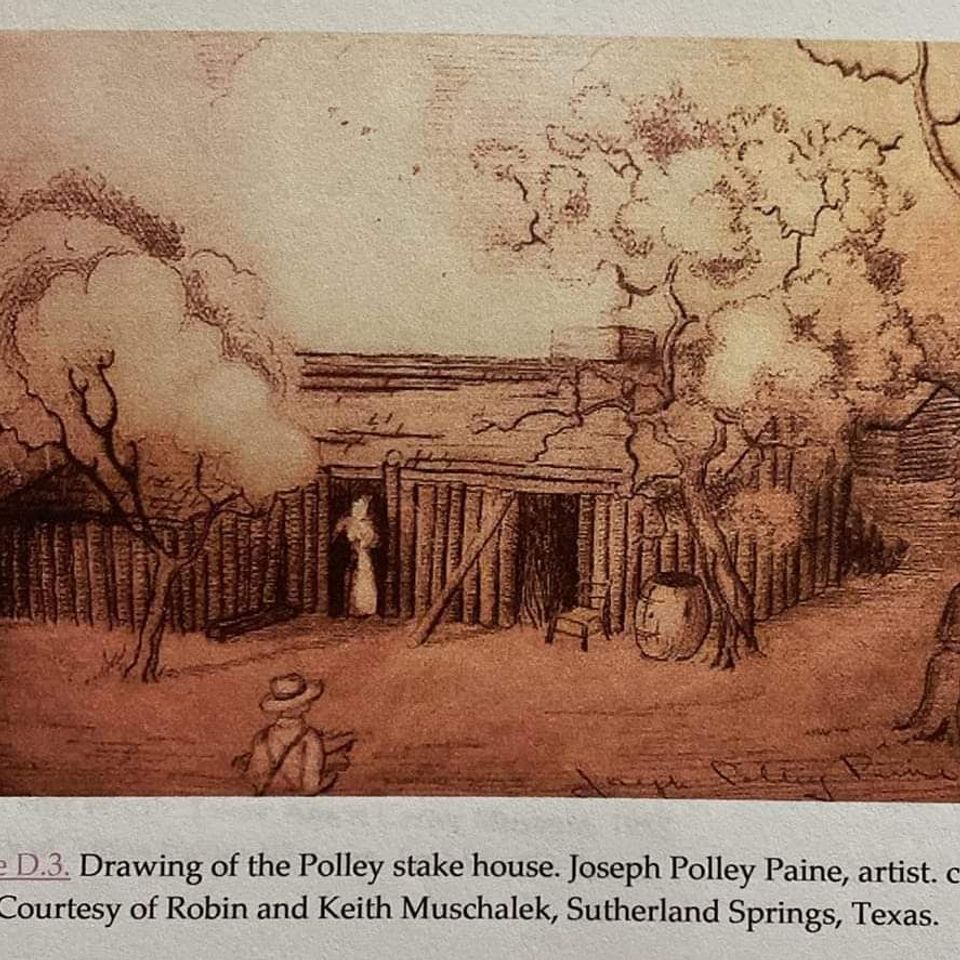

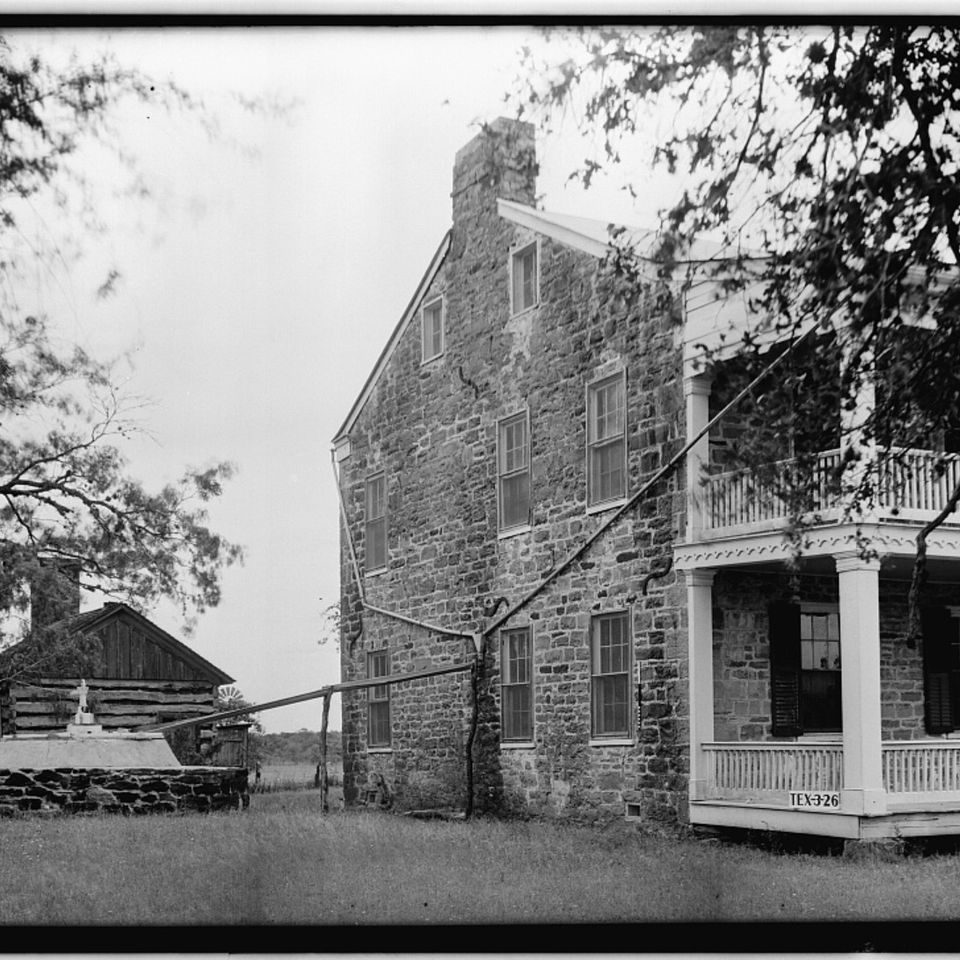

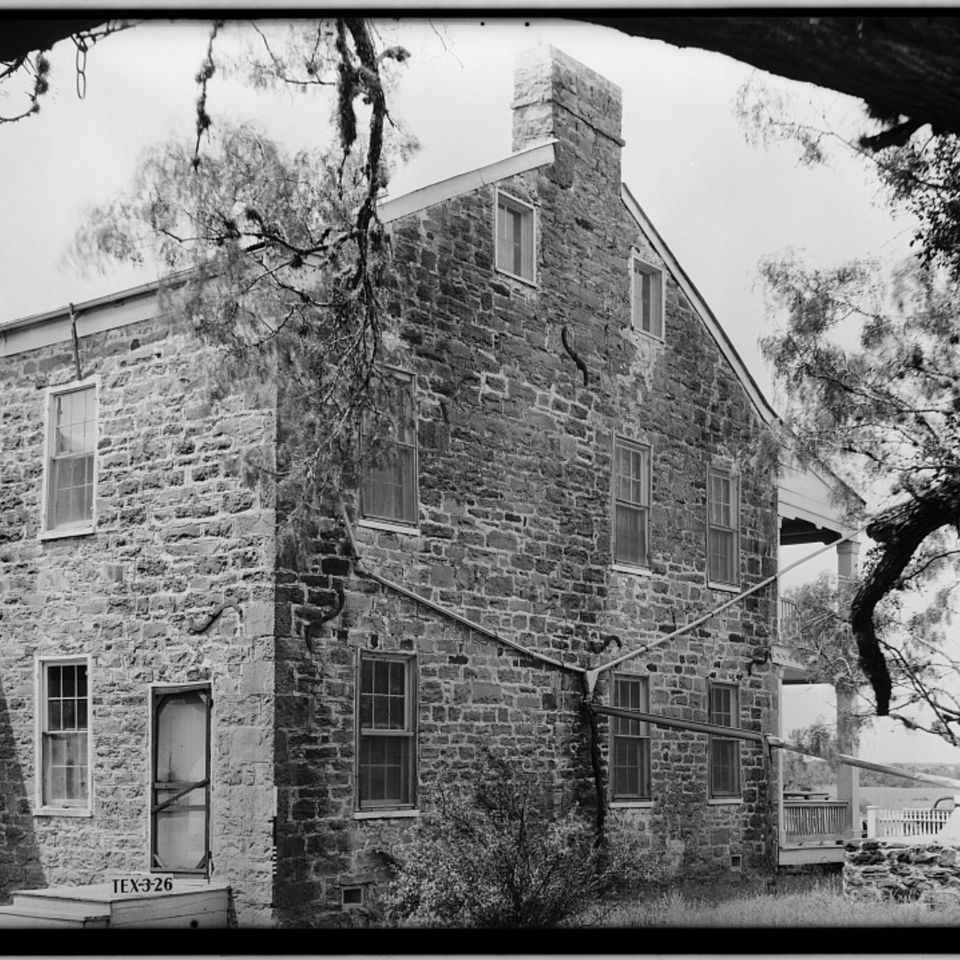

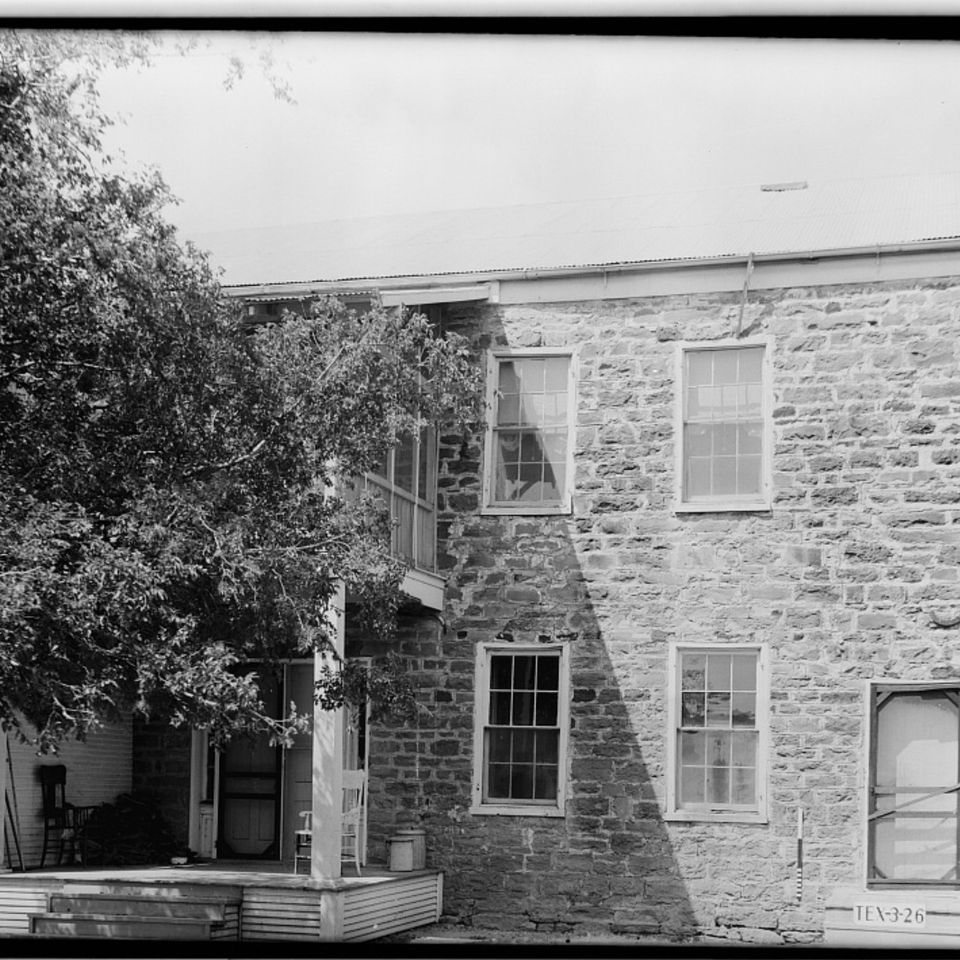

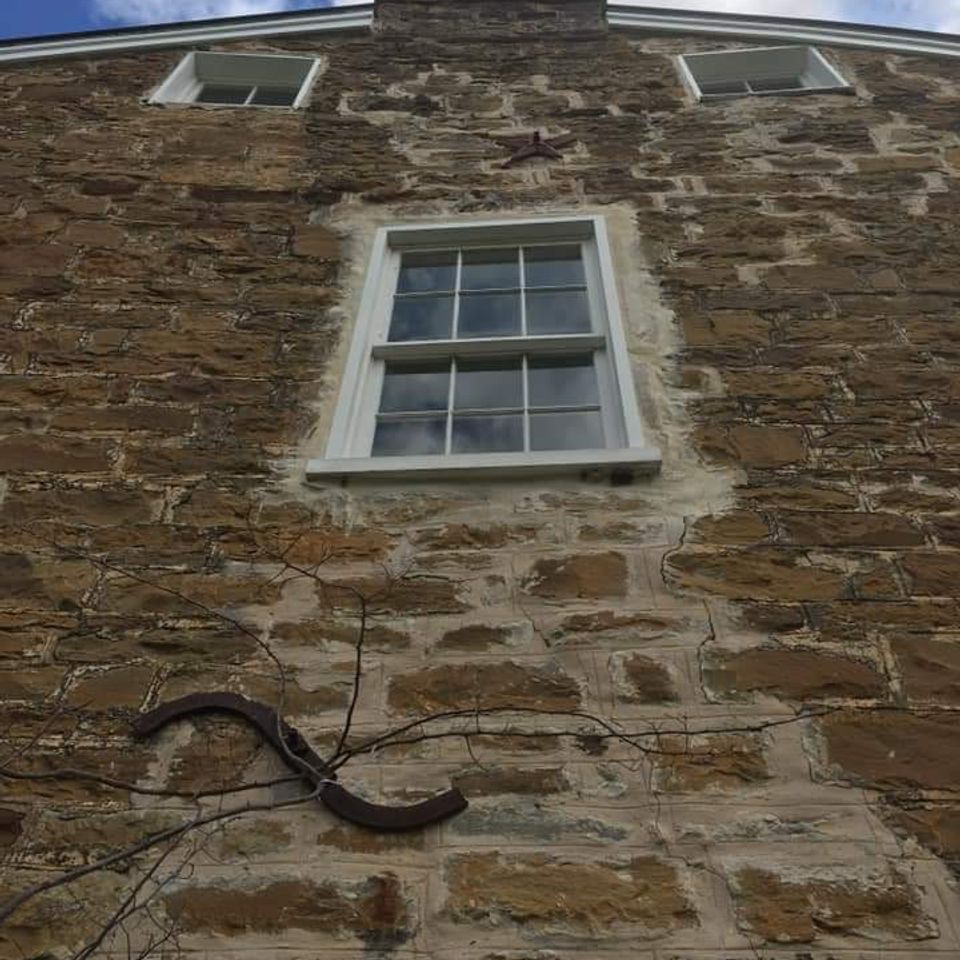

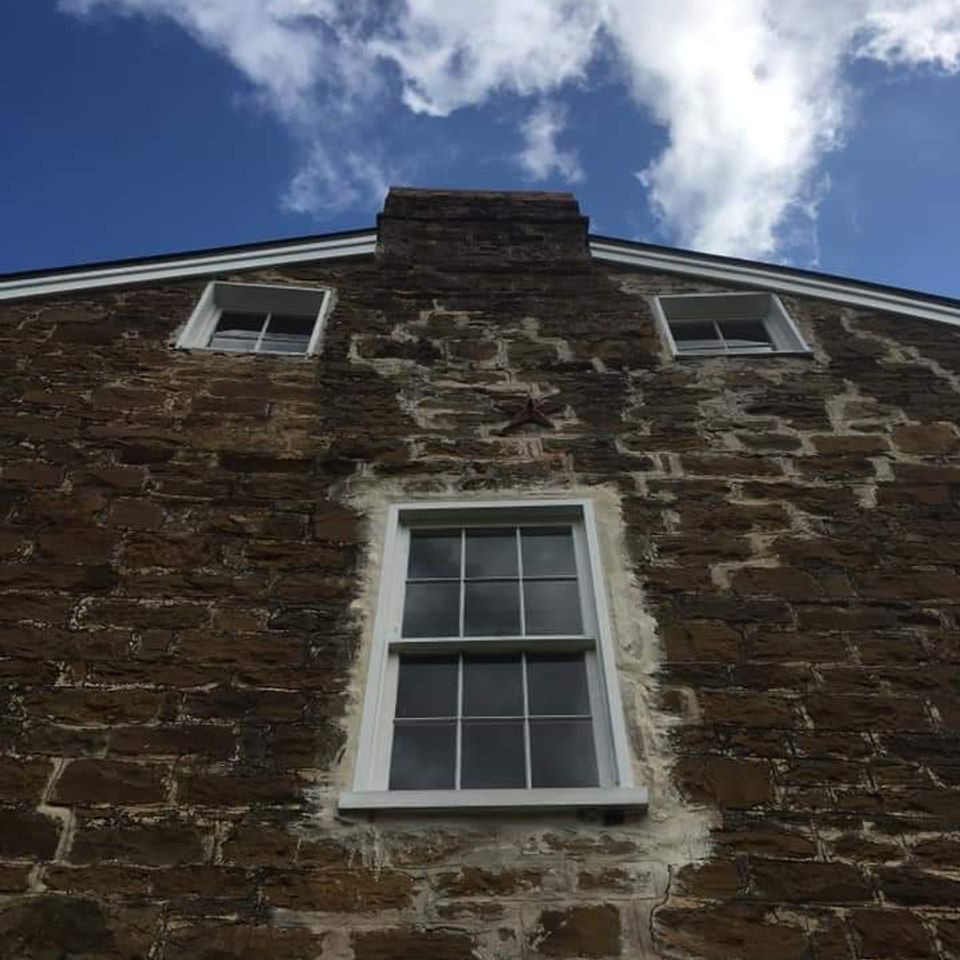

"I was just 10 years old when the Indians made their last attack and depredation in our country. There was a large band of them and they were out to kill and do every other kind of meanness they could, including driving off all of the live stock. Ten miles above us on the Cibola they murdered a black woman and coming on down five miles they killed Jewett McGee, the son of a Presbyterian preacher. Father had built a big two-story rock house in 1854, the largest building in all of that section, and when the folks in the settlement, for it was fairly well settled then, heard of the Indian devilment and the route they were taking, they all hurried to our house.

"We had moved into it before it was completed, but there was plenty of room and we were glad to have our neighbors with us. It was the best opportunity we children ever had for a real playfest and I remember how rebellious we were because our mothers would not let us play in the yard. After a long wait we heard the band had passed within three or four miles of us. Just after they got by, a newcomer, from Missouri, who owned a fine blooded bay horse, came and told father and the neighbor men about it and they got things ready immediately to follow them, Colonel Wyatt, in command, was tendered the fine horse as a mount and they made good time, reading signs easily and feeling sure of successfully overtaking them, when it began raining and washing out the traces so that it was difficult to follow their route. But they persevered until in crossing the San Antonio River it was discovered that their store of powder had become watersoaked. Of course that put an end to all of their plans and they were forced to abandon pursuit.

"In 1854 John James of San Antonio drove a herd of cattle to California and father sold him 150 head of the cattle. I was only 9 years old, but keen to drive, and father permitted me to go as far as Caswell, where our delivery was to be made. It was scary times all right, for Indians were everywhere. One night we camped on the Leona and penned the herd because of a heavy fog that made it so easy for the Indians to creep up without us seeing them. We were afraid to drive further, although we were only a short distance from Caswell at the time. Next morning the fog still hung thick all around us and we did not turn the cattle out until it cleared up. About 9 o'clock it lifted so that we could distinguish objects in most every direction within a reasonable distance and we started the herd, making it to our point of delivery without seeing, or suffering any outrage from Indians. The buyer of the cattle held them right there until dark of the moon on account of what the boys told him about suspicious indications of Indians being on the watch for a chance to raid.

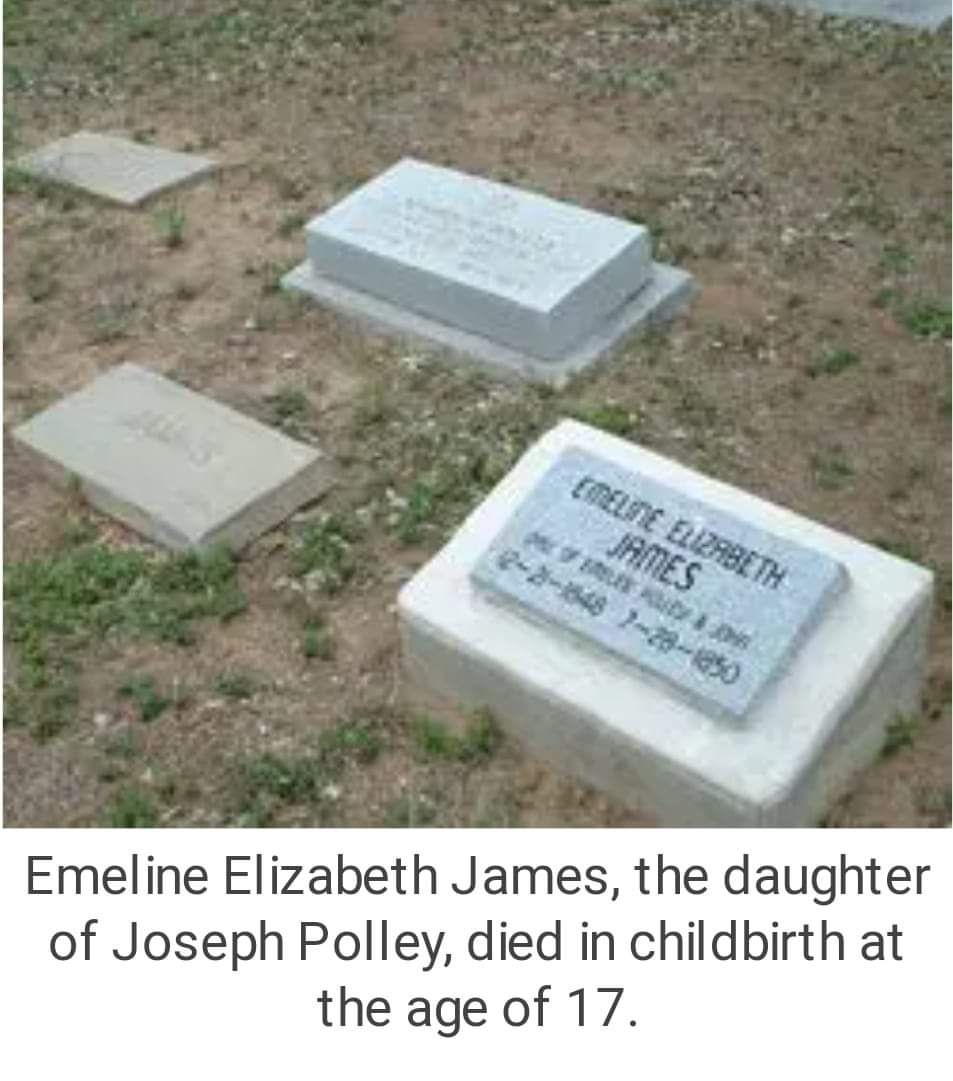

"From there we went to San Antonio, where I put up at the Plaza Hotel with the other cowboys and felt bigger than any of them did, as we took in the sights of the city after dark. I recollect well, that Bell Brothers, jewelers, were then located in an adobe building where they were melting silver to make teaspoons, to me a marvelous sight. If my memory serves me right, John H. James was the owner of the only two-story building in town at the time. James' first wife was my sister and when she died he married again and because it is such a rare occurrence I want right here to state that his second wife was just as good and kind to my parents and their family as my own sister could have been. Vint James is the only one of that family now living.

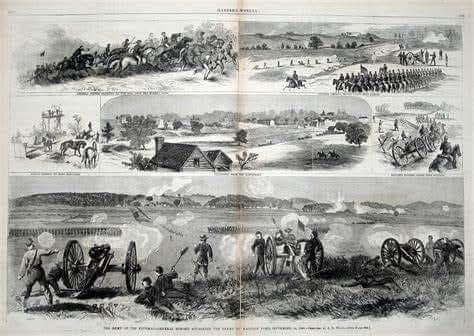

"In 1862 at San Antonio I lined up with the Confederacy at the age of 17 years and served two years through "shot and shell, and war is hell" on the border. The spring of 1864 found me home again, where I worked the range for my father until I was 21.

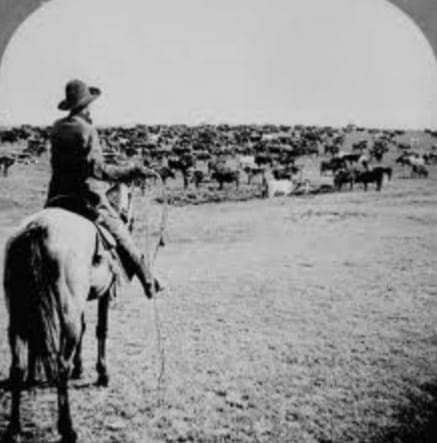

"At that time father owned two ranches and when I had turned my majority year he appointed me manager of the west side of the San Antonio River. My nearest ranch neighbor was five miles away and the next one ten. There was no farming being done then to amount to anything . Everything was cattle and horses. I had a big outfit and a bigger job, but I handled it all by myself. But I hadn't any spare time in doing it. We owned about as many cattle at that time as anybody in the State. I remember the year of 1862 we branded more than 6,000 calves on the two ranches, not counting those on the range at rounding up time, and from then on the increase was enormous. It took everlasting keeping at it to keep up with all of the cattle, with the range reaching, it seemed then, from one side of Texas to the other. But I stayed on the job until 1871.

"Trail driving was running high then, and I decided I would give it one round if I was just 21 years old. Father told me to go to it if I felt I wanted to and I gathered a 1,000 beef cattle to start. Falling in with Frank Newsome from Goliad County, who had been up the previous year and was going again, I persuaded him to go along with me, or that is to drive in close proximity as the trail was an old story to him. And I drove that herd from Kansas County to Ablene. Kan., without so much as a stampede. I have always given the credit for that to Newsome, for he helped and guided me like a father and was one of the finest, cleanest men God ever made. He was familiar with every watering place, knew where we should camp and all such things that make for safety and meant a lot in handling cattle on a two or three months' drive, and saved a fellow a whole bunch of trouble.

"In almost every county we passed through, bill of sales to the cattle we drove, had to be produced when asked for by the officers, and Newsome was held up on it every time, while I got by with only one showing—at Denton, Texas. Never could figure it out either, why they let me go on without molestation and bothered him, unless it was because I was so young and full of pep and determination that they took it for granted that I knew what I was about. It has always been a mystery to me for there never was a straighter, better man than Frank Newsome and he was much older than myself. I reckon it was just a happen so and that it might have been the exact opposite the next trip.

"I forgot to say, awhile ago, that I was married the year before I made that drive, to Miss Belle Beverly, daughter of Judge Beverly of Dodge City, known to the trail drivers as one of the firm of Wright & Beverly owners of the largest dry goods and clothing store in Dodge City. We began our home making in Karnes County near the Beverly homestead. But Belle had promised her mother, and mine, to divide time staying with them in my absence. I was not uneasy about her safety while I was away, but I was young, high strung and very much in love with my wife; so when we reached Abilene I turned the cattle over to Judge Beverly to sell for me and I took the back trail. That trip then, was no twelve hour affair either, I want you to know; for we went by train to New Orleans, thence by boat to Galveston, from there by rail again to Columbus and finally by four-horse stage to San Antonio. Nor was my journey completed then, for I rode horseback to our Cibola ranch, having a hunch that my wife would be with my parents about that time, only to find when I got there that she was at Mrs. Beverly's twenty-five miles further on, and I didn't mark any time in making that distance I am telling you.

"I stayed home and worked our cattle then until the spring of 1872, then I put another trail herd, expecting to take it up myself. But having the chance to sell at a fair price I did it.

"The railroad was then under way between Victoria and Cuero and it struck me that by taking a bunch of horses down there and making a contract to get out railroad ties I would make some good money. But, as sometimes happens, it was a costly experiment. I lost more than I made and went back home a sadder and wiser man. Most of the settlers then had begun to give farming a trial and I decided that if they could succeed at it I could, too, or at least make a showing. So I pitched in and made a good crop, selling at a fair price the year 1873. But the following year was a complete crop failure and I can not say that I was half as sorry as I should have been, for no cowman takes to farming like a duck to water, and it is generally a sort of 'hafto' proposition when they tackle it.

"I lined up with Sebastian Bell in the cattle business again and felt better satisfied. My agreement with him was that I should come out and help gather a herd of cattle, do the driving, he paying me wages while I was about it. Then, in the spring we were to sell and divide profits fifty-fifty. I rounded up quite a good-sized herd, put it in the pasture to winter and in the spring I went down on the King Ranch intending to work the range back and bring in all I found wearing our brand. When I got hack I found Bell had rounded up all of the cattle I had put into the pasture, sold them and met me with the suggestion that I gather another herd for my share. I told him there was nothing doing; to pay me my wages and buy my horses and I would go hack the way I came. It was done and I left his employ just that way.

"George West had a bunch of wild, bad brush cattle that he wanted to sell and I went to San Antonio to arrange for money to buy them. While there I met Tobe Odom, who, after hearing my plan, said: 'Huh, there is no one man on earth that can handle those cattle in one herd. They are paying good prices at Austin now. Suppose we contract them a hundred or two hundred at a time, sell them and make some real money.' I agreed to that, but it so happened that we could not do any contracting, and I, after spending what money I had trying, decided that it began to look like farming for me again. However, I made one trip up the trail—the year of 1875 that was, came back home and went to working my own stock. Then in the spring of 1876 I sold my ranch and farm and went to Floresville and turned merchant.

"Early in the year of 1877 I went to San Antonio to stock up on store supplies, and, having a few minutes of leisure one day, I went around to a friend's office to say hello to him. He greeted me with, 'Hub Polley, the very man we are looking for. ' With that he introduced me to a Mr. Frasier, saying 'You are looking for a man to take charge of your herd on that trail drive. This is the one right here and you could not find a better or more reliable one in the world.' Frasier was a Scotchman, a sort of quiet-like kind of man, and he said: 'Mr. Polley, let's go and have a glass of beer.' While we were drinking he said again: 'Will you take my cattle up for me?' I replied, 'Well, I will if you wil l pay me for it. I have been done so much lately that I am sort of dubious about taking a job any more and my mercantile business is going pretty fair now.' He answered me with, 'I will pay you $125 a month and furnish everything. If that will be satisfactory to you, we will go right over to the bank and I will identify you so you can get what money you will need for supplies.' I said 'That suits me fine. ' When we walked into the bank first one and another of the officers and employes began shaking my hand and talking to me, and Frasier, standing around watching them, finally came to me and said: 'By gracious, they know you a blamed sight better than they do me. I guess you won't need any identification here.' Right then he put things entirely in my hands, saying, 'Polley, you go right ahead and take full charge. The outfit and chuck wagon are ready whenever you are. We have a few cattle, but you will have to buy more, a quantity sufficient to make up a good, strong herd. I will bring you the cash to pay for them, for you will have to have it in dealing with Mexicans. They will not take checks.'

"I went hack to Floresville and put the proposition before my wife. She thought like I did, that it was best that I should accept it, so I straightened out the business, hurried back and went right out to looking up and buying cattle. When I needed money to pay for them Frasier was right with it, 'Johnny on the spot. ' I remember one time he gave me a $1,000 bill and I had to carry the thing around in my pocket a month or so before I could get rid of it.

"Finally I had 2,500 head together and I took the outfit and drove them through to Dodge City, where I made delivery and settled up with Frasier, who said to me: 'Hub, I will put up the money if you will go to Texas, buy up a herd and trail it up here. We will sell it and divide profits. How does that suit you?' I said 'I like the idea.'

"I thought over Frasier's offer and knowing him to be strictly on the square, as well as feeling a little flattered by the confidence imposed in me; and the lee-way he gave men in handling his cattle. I told him that I would take him up on his proposition. I came back home and starting to buying right then and the fall of '77 we had fine grass so cattle came through in good shape. I bought all of that winter and when spring came I had 2,500 cattle on hand.

"There were two brothers, named Brothers, who wanted to go along with me when I started my buying in Mexico. They were in the same business and did not know Mexicans as well as I did. I told them I would be glad to have them. I put $5,000 in silver and $1,000 in gold into some boxes and set them in the wagon. The gold was for custom money for if we brought cattle across the Rio Grande it required gold to do it. Then with $3,000 in currency in my pocket to pay for my purchases I started down into Mexico. Brothers put his money in his wagon, something like $9,000 in silver, perhaps a few hundred more. Anyhow we had together somewhere around $19,000 or $20,000 along with us. When we reached the cattle country I contracted for some cattle and went to buy some horses over in another section, leaving a Mexican in charge of the cattle to put a good taste in the mouths of the others around about there. When I returned he said to me, 'Some men came while you were gone and offered the owners of the cattle more money than you were to pay for them so they have agreed that you can not have them.' Knowing Mexicans like I did, I felt pretty sure that it was a frame-up, so I said nothing much back to him. But I told Brothers that we would stay 'round a spell and see what came of it. The third night after that I noticed that both the Mexicans and cattle were gone and I said to the boys, 'I smell a mouse. We are in the middle of a bad fix or my name is not Hub Polley. Those rascals are planning to raid us, knowing that we have a lot of money. We could put up a pretty stiff fight but I believe the best thing for us to do with our two outfits is to hitch up, get out by daybreak in the morning, make for Corpus Christi and put our money in the bank."

"They agreed that it was a good plan and we acted upon it. I rode with the wagon to within two day's drive of Corpus Christi. Then I came back to see what had happened to the few cattle that I had bought and paid for. When I rode up to the place where I had been camped I found that by thwarting the devilish plans of those scoundrels I could buy all of the cattle I wanted. Moreover that I could get all of the money necessary to swing a deal and give checks for it. There was a Mexican at Paloma running a store, from whom I had bought 150 cattle, who was so gracious to me that he told me he would stand good for any amount I needed until I could go over to Rancher Davis and get it.

"When I started to get the money at Rancher Davis I took a Mexican along that was a pretty square sort of fellow. He said, 'We had better not leave here until after dark. We are being watched and I don't know what might happen.' I took his word for it and when night came we mounted our horses and struck out. About midnight we came to a little draw and being tired and sleepy I said. 'We will pull down into that thick mesquite brush and sleep awhile.' Next morning, the Mexican awoke me with, 'Look yonder.' I roused up and not far away from us there lay five or six Mexicans sound asleep. They followed us and not finding where we went, they lay down to sleep until morning. 'We had better keep quiet and get away as soon as we can,' said my man. Again I took his advice and we made a quick get-away to the store of the Mexican where I made my headquarters for those whom I owed to come and get their pay. After that I bought 1,000 cattle more and knowing that I could get all that I heeded in Live Oak County to finish out my herd, I left it with them. Glad enough I was to be dealing with sure enough cattle men on my native soil once again I tell you.

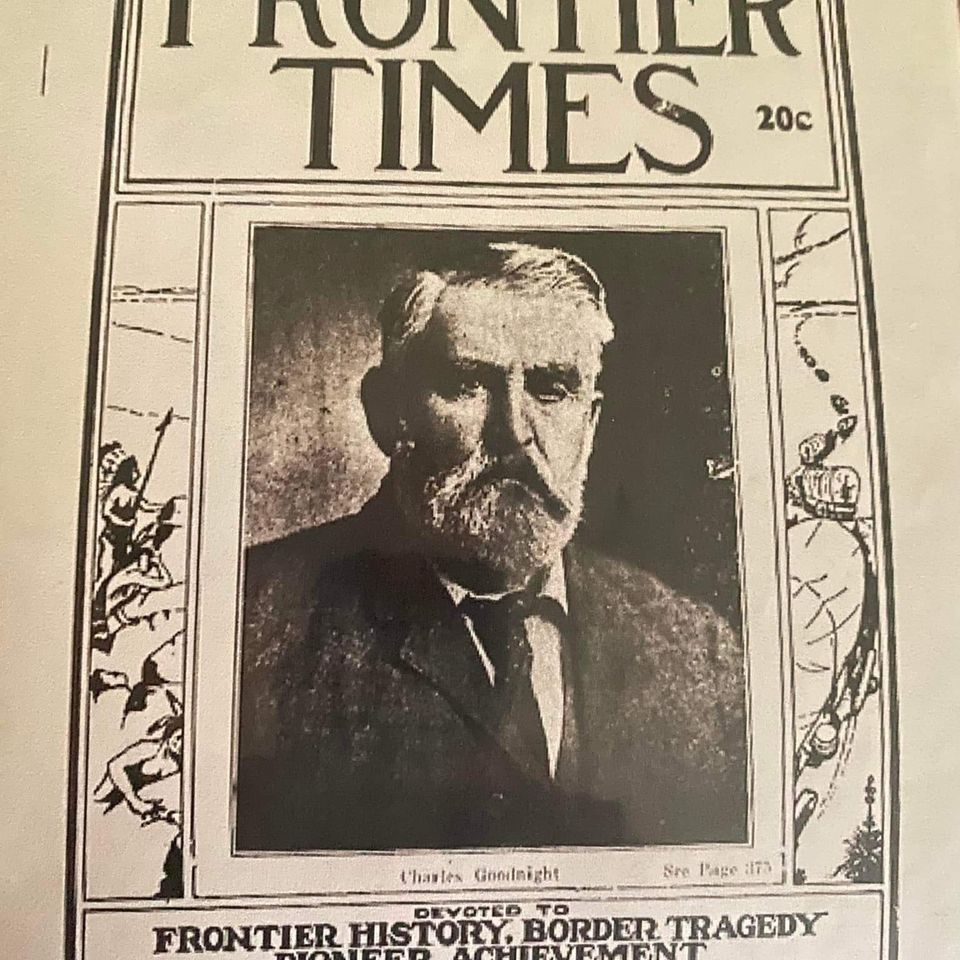

"I bought 1,500 more head, then hit the trail for Kansas with my 2,500. At Fort Griffin I received a letter from Frasier in which he told me that he had sold the herd at Adobe Walls, on the Canadian River, to Bates and Beall of the Turkey Track ranch. Then followed directions telling me how to get there. I followed the instructions exactly and the road he specified led me to Adobe Walls, where Charlie Goodnight ranched. There I met him for the first time. He told me that it was thirty-five miles farther to Bates and Bealls' place, to follow the next intersecting road and it would lead me there. I did as he said and shortly wound up there and delivered the cattle.

"Frasier met me and after we had settled up our business we left for Dodge City together. There, after talking things over with my father-in-law, Judge Beverly, I decided that maybe it would be more profitable for me to move up there. I wrote my wife and told her to be ready when I came for her for we must hurry back. When I got to Texas she was not only ready but had everything shaped up for an immediate journey and we were on our way right now. The trip was uneventful and quickly made, for those days of slow transportation, and when we arrived I found my job already cut out and waiting for me—a fellow wanted me to hold 3,000 head of cattle there to fatten. Late that fall he took them off of my hands and I stayed at home with my folks until the next spring.

"Next day 1,200 more came in. We counted them out and again I wrote a check in payment, at Evans' instruction. This done, we consolidated the herds and Evans said. 'You hold them until I get somebody else to do it.' I herded them around there about a week and one day he said, 'Look out a good place to hold these cattle, Hub; I will find somebody before long to take care of them.' That was in June. I found the place, all right, took care of them and waited to see when I was ever going to get back on that 'easy job' Evans promised me. About in October Evans came to me and said, 'Hub, we want to establish camp on the Wichita and I want you to lead out with this herd and select the place for winter headquarters.' It was a 100-mile drive, with no settlements to obstruct the way, so I struck a bee line west, hit the Wichita and pitched camp. Next morning I took two of the boys and went up the river looking for a permanent camping place. About twenty-five miles farther upstream we found it and I sent word by a man to Fort Reno that I had established a camp and they could send on the other cattle. We went into winter quarters with 10,000 beef cattle right there. It was as fine a grazing place as one could want, grass was good and the cattle came through in fine shape.

"Our men were employed all of the time during the winter to drive the beeves to Fort Reno and Anadarko; delivery was to be made twice a month to the Indians there. Sometimes the cattle were delivered to the Sac and Fox agencies, also to Fort Sill. Believe me, I was one busy man, for I had to be on hand at every delivery made, to stand by the side of the agent as each animal was weighed out and see that the weights were correct. Some job, when you stop to consider how many cattle we turned in that season. But those Indians thought I was just about the correct thing to stay with them like that and see that they were not cheated in weight.

"Our contract with the Government did not expire until June, 1880, but long before that time I had a telegram from a man named Healy, asking me if I would go to Padre Island in Texas, gather a herd of cattle there and drive them to Kansas. I replied that I would if I could get away and would take the contract at $150 per month. Putting it up to my company, they said that if I would come to St. Louis and put the books into shape they would let me off to make the trip.

"I was to meet Healy in Kansas City, just 250 miles from Dodge City, where my wife was, whom I had not seen in six months, and, would you believe it, right there I waited a whole week for that man to meet me. When he finally showed up he said, 'I have got to go down through Missouri and you can go on up to Dodge while I am gone. I will meet you in a few days in St. Louis.' I did not need any urging and started on the trip that very day. But having the impression that he would not be away but a few days, I only stayed with my family two days before going back to shape up my books and be ready to start when he was. I finished my work and put in another ten days waiting on Healy and thinking what an idiot I was to leave my loved ones so soon when I might have had such a nice visit with them. But I had a delightful stay, with that exception, for old Captain Evans, formerly of Gonzales, Texas, showed me one fine time.

"We left the day following Healy's return, by train to Galveston, from there by boat to Indianola and the next day, after landing, I took a sailboat to Corpus Christi and made a deal for sixty head of horses; then went to Padre Island to begin work. Having previously arranged for supplies to be delivered, I was somewhat surprised when I arrived with my outfit to find nothing to eat. But no provisions were in sight, nor any boat, either. We were hungry, having done without dinner, so we started on a foraging trip, or perhaps I should have said on one of investigation. Anyhow, we came up with a fellow bathing sea gull eggs and we bought enough for our supper. Now, gull eggs, eaten without salt or bread, could be improved upon, no doubt of that, but we ate them ravenously for all of that, though I can not say much for their filling qualities when eaten that way. Alongabout midnight I heard a boat land and, later a cargo being docked, or at least that was what it sounded like. This, in turn, was followed by somebody bringing something into our camp and I got up to inquire about it and was told that it was the man with our supplies. Asking why he was so late about getting them to us, the reply was, 'I wait for wind enough to sail the boat.' News to me, that was, although if I had given a minute to figuring it out when I was so worried about supper time doubtless I would have felt less uneasiness about the possibility of doing without breakfast. I was familiar with the hurricane deck of a buckskin cow pony, all right, but running a sailboat was entirely out of my line.

"We had a good breakfast and then came the problem of how to get those cattle off of that island to the mainland. Rounding them up and getting them shapeu to move was the first job, and then we figured out a plan to get them ashore. We waited until low tide every day and by driving 400 or 500 at a time across to the pasture I had secured about thirty miles away, we finally put them all over. Then branding was in order. With that accomplished, the chuck wagon provisioned and all of the other details attended to, we were off on the home run, meaning the cattle trail.

"Things went as smoothly as could be expected until the cattle became accustomed to constant driving. We found our first obstacle the Nueces River, which was out of banks. There we waited a month for it to recede with seemingly no prospect of its doing so before spring. So we pitched in and swam it which I would never have done had I foreseen that which occurred. That is that we would lose six good saddle horses and forty head of cattle by doing it. Yes, sir, that is exactly what happened. You see, the water was so high that the tops of the trees on its banks just showed enough of their tops above the water for the cattle to get caught in the branches and lodge there so they could not get out. In that way forty head were drowned, together with the horses mentioned. That left a pretty bad taste in my mouth and I resolved to write the owner about what to do in such crises should occasion arise again en route.

"It rained on us pretty nearly every day until we reached Fort Griffin, and there we found the ground as bare of grass as a floor. I knew the herd should be pushed on but I found a letter from Healy telling me to wait until he came to meet me. I wrote him the condition of the country, that there was no grazing for the herd and so on, but that would hold, subject to his orders. Finally I received a reply saying, 'Stop the cattle there until I come.' And there I stopped them, some of them for good, too, for they were poor to begin with. They were famine-stricken at the end of that ten days' wait, with nothing more to eat than was to be found in an open road. When he got there and I showed him how the cattle looked and the condition of the range, he smiled and said. "They will be all right, cattle can live anywhere.' No cowman at all, did not know hte ABC's of the cattle business. But my instructions was to hold them close.

"Realizing that cold weather was at hand and that those cattle had to have some shelter or they would all die, I made a drive of two days and when we got to the Canadian it was frozen over. It was the 15th day of November and a blinding snowstorm had set in. I was between the devil and the deep sea,' for I knew if in crossing the cattle over the river the ice should happen to break under their weight it meant they would all drown or freeze, on the other hand they would starve and freeze if they were not crossed so they could have the protection the brakes and canyons afforded. Considering it seriously from both sides of the question, I decided the least risk would be in crossing; so over they went, as it happened without breaking the ice. I deployed them in and around the canyons, where, despite the snow, they could get quite a little picking, and when that storm was over 600 head of them had frozen to death. Again I lost horses, too, an even half dozen.

"I found that Doc Day had gone into winter quarters on that side of the Canadian and I arranged with him to winter and deliver what cattle were left in the spring to Healy. He afterward told me that he got an even 500 head of the original herd at the spring roundup. They were so poor and it was such terribly cold weather, they died by the dozens. But I have always believed that if Healy had let me go on with them across the river instead of waiting for him that ten days at Fort Griffin, with no grazing for the herd, that he would have gotten most of the 1,280 head that I crossed over when it was so bitter cold. Anyhow, that made the most interesting drive I ever made, if it was the most disastrous.

"I bought another herd and trailed it from Clay County to Dodge City for a man by the name of Moore. That winter I stayed at home for a change and the spring of '81 Wright and Beverly Texas as Fort Griffin and drum the trail for them, in other words be a traveling salesman for supplies from the store in Dodge City, that being the last trading point en route north . I did it and when I got back to Dodge City here came a letter from Conrad, a supply dealer at Fort Griffin, who had moved to Albany on account of the railroad building in there and he wanted me to do the same kind of work for him. I accepted his proposition and worked it again from both ends of the trail, for Conrad in Texas and Wright and Beverly in Kansas, and made a good thing out of it for myself as well as the merchants I represented.

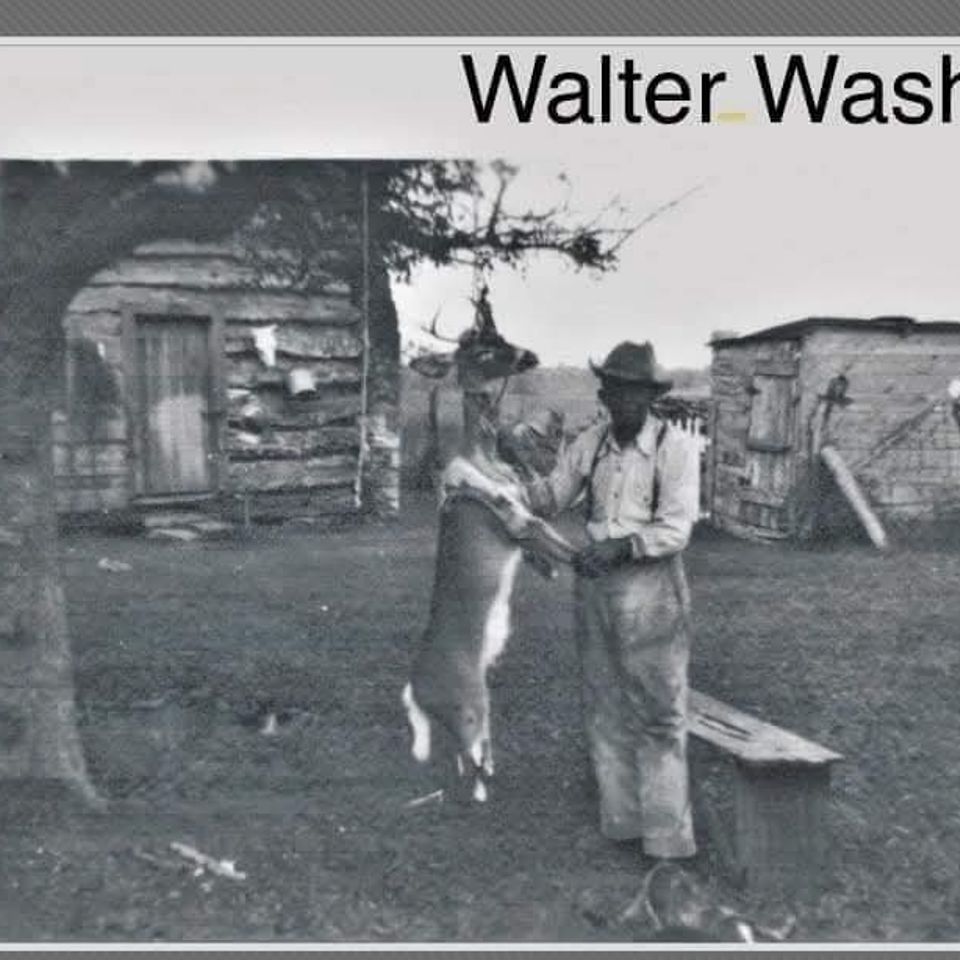

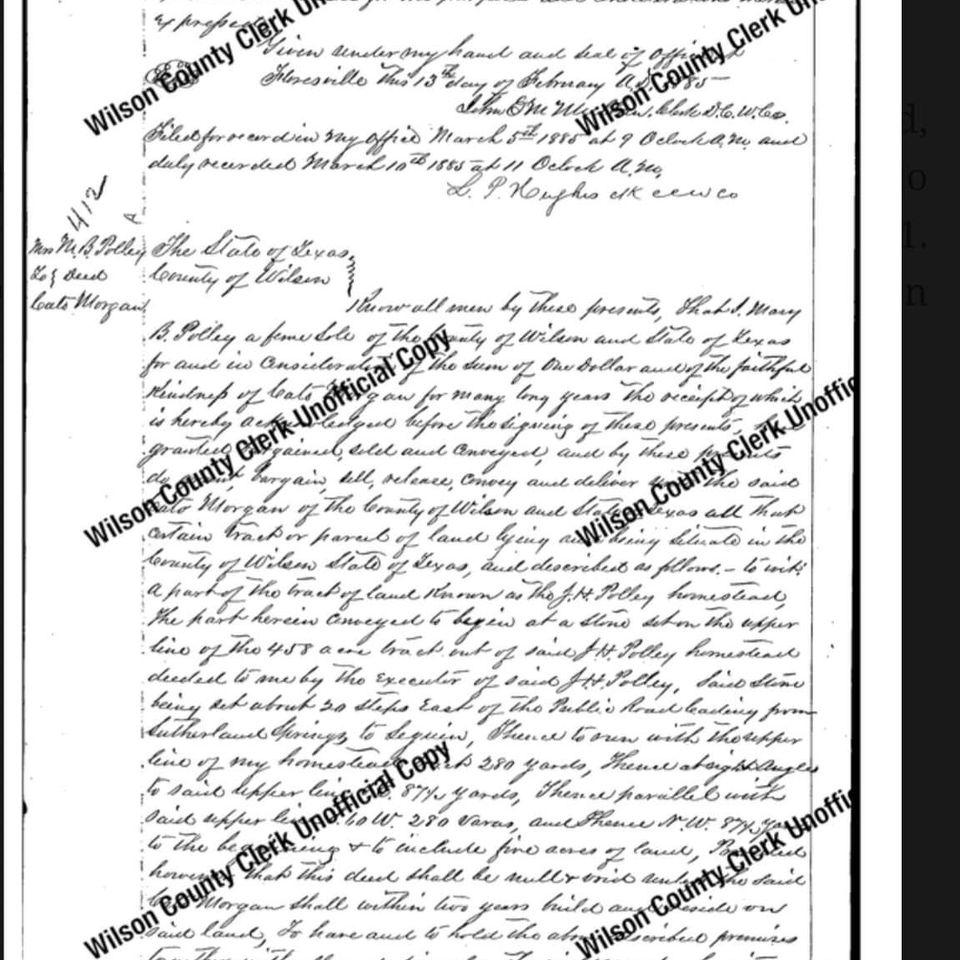

"The following June I came back to Texas to the old home ranch to see mother, for I was lonesome and blue, having lost my wife three years previous. Cattle were at their peak then and I went partners with brother Walter, bought heavily and went broke. Mother had left the old home and was dividing time between her children's hearth-stones, but she said, 'son I want to go back to the place where my children were born and where most of my life has been spent with my family.' I said, 'well, mother you come right on and we will go together. I know I can farm enough to make a living for us until I get on my feet financially again.' And we went. The old negro that I told you about in the beginning, who was cornered by the Indians at tha Mustang grapevine and who made it back to the house, had married a good negro cook and housekeeper and with them to do the work we got along nicely. But lonesome! I never was in a place that seemed like it was sa nearly haunted as that old home. Memories stalked in every room, phantom faces looking across the table and ghostly figures sat around the fire place until I just could not stand it. There was a neighbor who lived near by with a charming daughter and I took to going over there to enliven the evenings, for mother, strange to say did not feel the depression that I did, nor the lack of company either. Well the long and short of it was that it was not long until I brought that sweet girl home for my wife and for the three years mother lived, thereafter, her own daughter could not have been kinder nor better to her than was my wife.

"In 1878 there was such a furore created about cattle trailing through Kansas to market that the 'nesters' were on the warpath about Western cattle passing through and howling like mad for the route to be changed so they would not be molested in this way. The Dodge City folks, subscribed $1,500 and $600 more was added to that at Medicine Lodge to pay someone to turn the trail route and prevent trouble, and how it was I never knew, but I was selected as the one best fitted for the job. I began going to Reno to see the Indian agent about a route I had in mind. But he would not listen to anything I said about it. Instead he demanded that we cross the Cimarron River three times in order to make the change we wanted to.

"At Medicine Lodge lived a fellow from Texas, who said that, he knew my people there and then, he added, 'I have got that $600 right here in the bank and you will get every cent of it as soon as the cattle are traveling the new route.' I was anxious to get at it, and, being assured of the money, I hired a man who was familiar with country to help me. The first herd to come by was driven by Gid Guthrie. I met him on the Wichita River on the return trip from my conference with the pesky Indian Agent at Reno. Knowing that all men like to feel that they amount to something when a crisis is at hand, I began at once to impress Gid with his importance to me in the changing of that trail, and I was not hypocritical about it, either. I knew that he was a good friend of mine, and I also knew that after one herd had taken the new trail it would be easier to get the second one to do it.

"With that in view I told him how glad I was, and I meant it, that he was the first to come by and help me map out the new route and so on, all of the time confident from the look on his face that he had no notion of taking any new path with his herd. At last we came to where the turn was to be made, me talking as hard as I could, with all of the assurance I could put into my voice that what I asked would be done. Gid was silent as the grave, with his face as inexpressive as stone. When it came time to swing the cattle he said, 'Polley, if any other man under heaven asked me to do this I would absolutely refuse. Do you understand? I am doing it for you, and I do not give a hang about it, excepting that you want me to do it.' I felt pretty good when I saw those cattle take that new route and heard old Gid' s declaration. I tell you it takes a sureenough, honest-to-goodness, dyed-in-the-wool friend to do what he did for me that day. The next herd went after his without much trouble and we did not have a great deal of grouching from anybody about the change. Not half as much as we heard from the 'nesters' on the old route. But I stayed right there at the turn on the Cimarron until enough herds had passed to make it plain for all that way and to show them just when and where the cattle were to turn.

"I had paid the man who led the first herd over the turn, John Moseley was his name, $600. Then Sam Kyger, who counted as correctly as I ever saw it done in the open, was given a steady job with me. And when we got things going so that all herds traveled the new trail I divided what money I had left with him, which was just $300. And believe me, or not, never a cent more did either of us see of all of that $2,100 subscription. But we turned the trail; no doubt of that.

"I was pretty sore over losing out on my trail contract, for it was hard work, but I never was a grouch, so I let it go at that and hired to Hunter Newman & Co., of St. Louis, who had a contract to deliver beef to the Indians. They had turned the business over to Jess Evans to get it going straight. He, being in Dodge City at the time, told me to take charge of the whole thing, buying, delivery and all. Well when we got to Reno we discovered that Hunter had already employed a man to do all that. So Jess said, 'Polley, I will give you a better job, not so much work, and not quite as much cash, but a darned sight easier to do, and that is keeping the books, acting as cashier, paymaster for the hands, doing the buying, in fact, attending to everything in a business way connected with the contract. That sounded all right, so I consented to it. The next morning Jess came to me and said, 'Hub, will you take charge of the 2,000 head of cattle that we have here now just temporarily, you know?' Of course, I said I would and we counted out the 2,000 head. He wanted me to give a check for money to pay for them. I refused. He argued that it was my place to do it and it ended that I did.

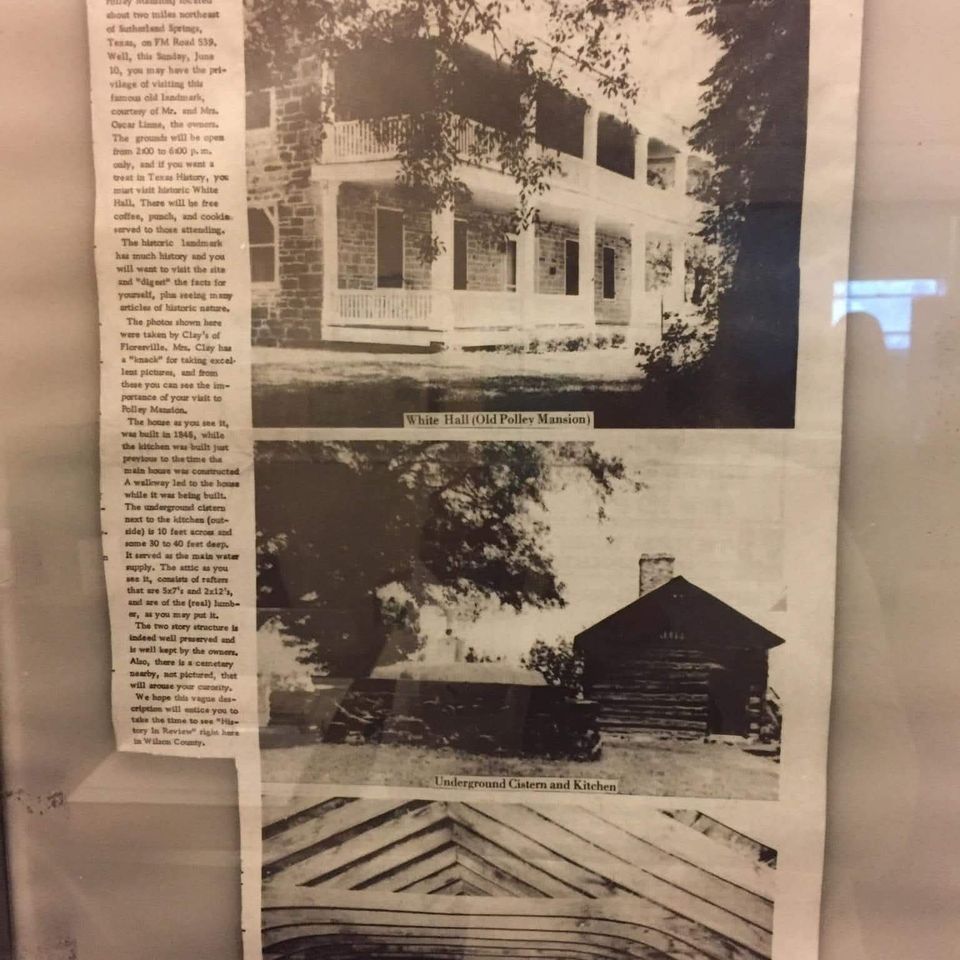

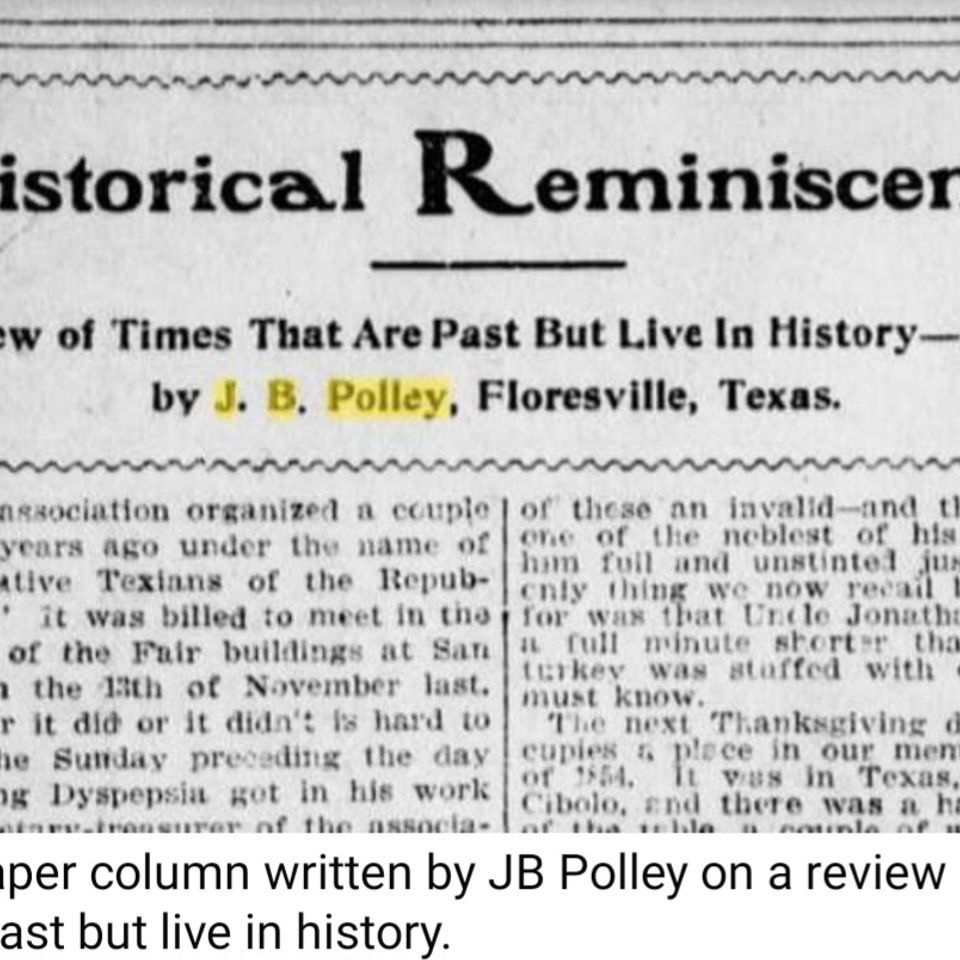

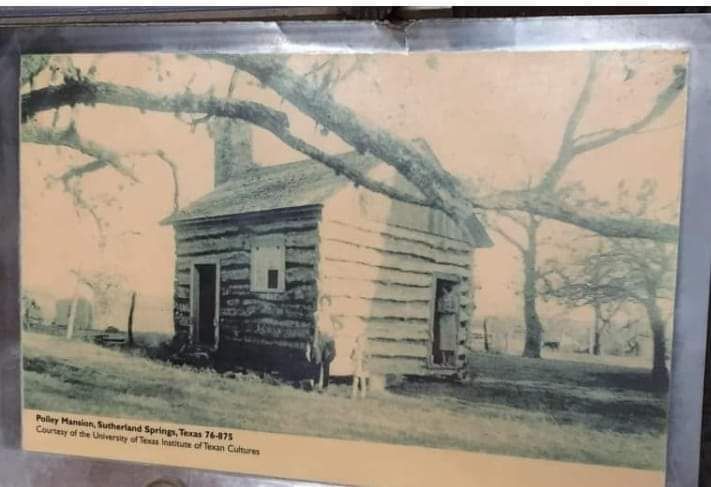

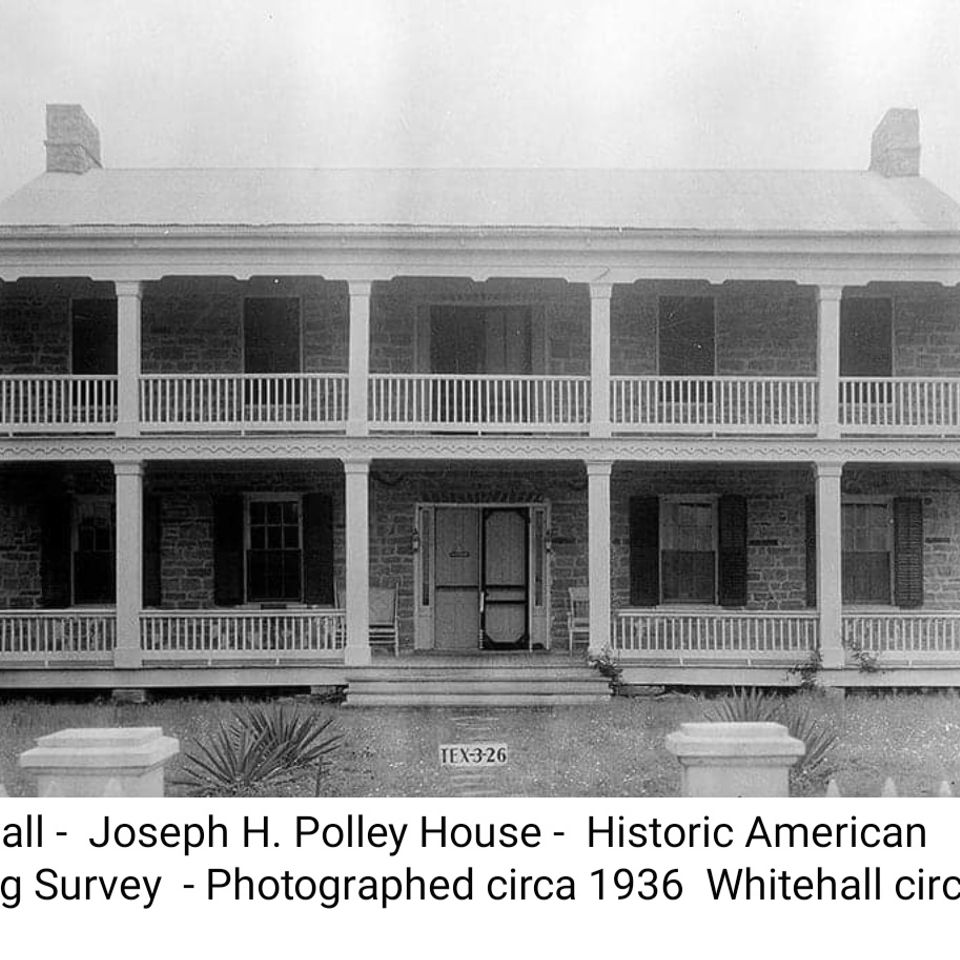

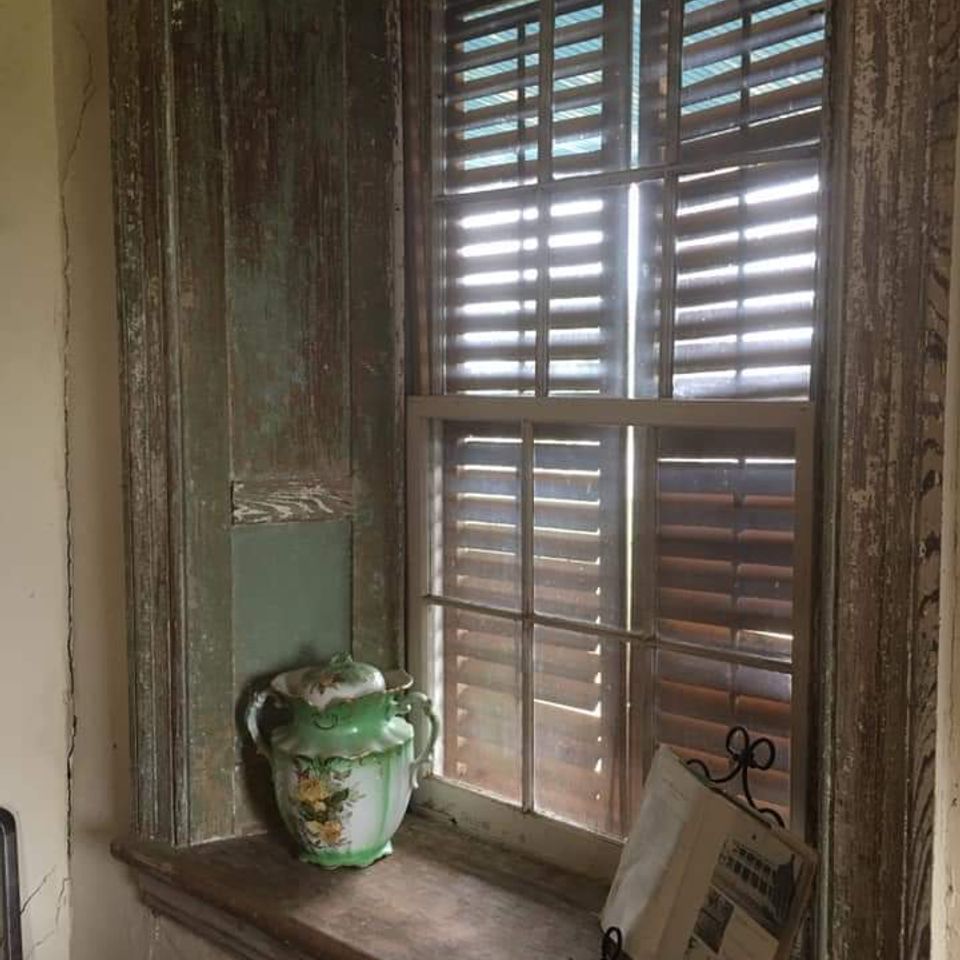

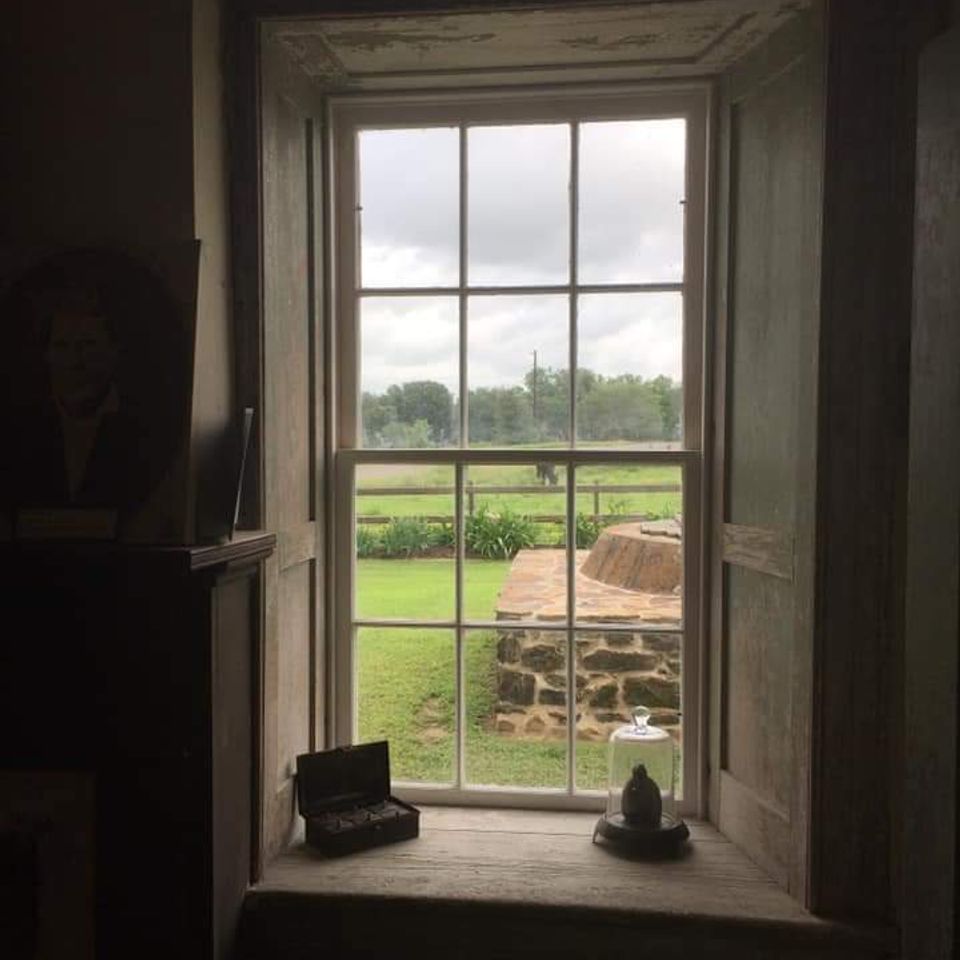

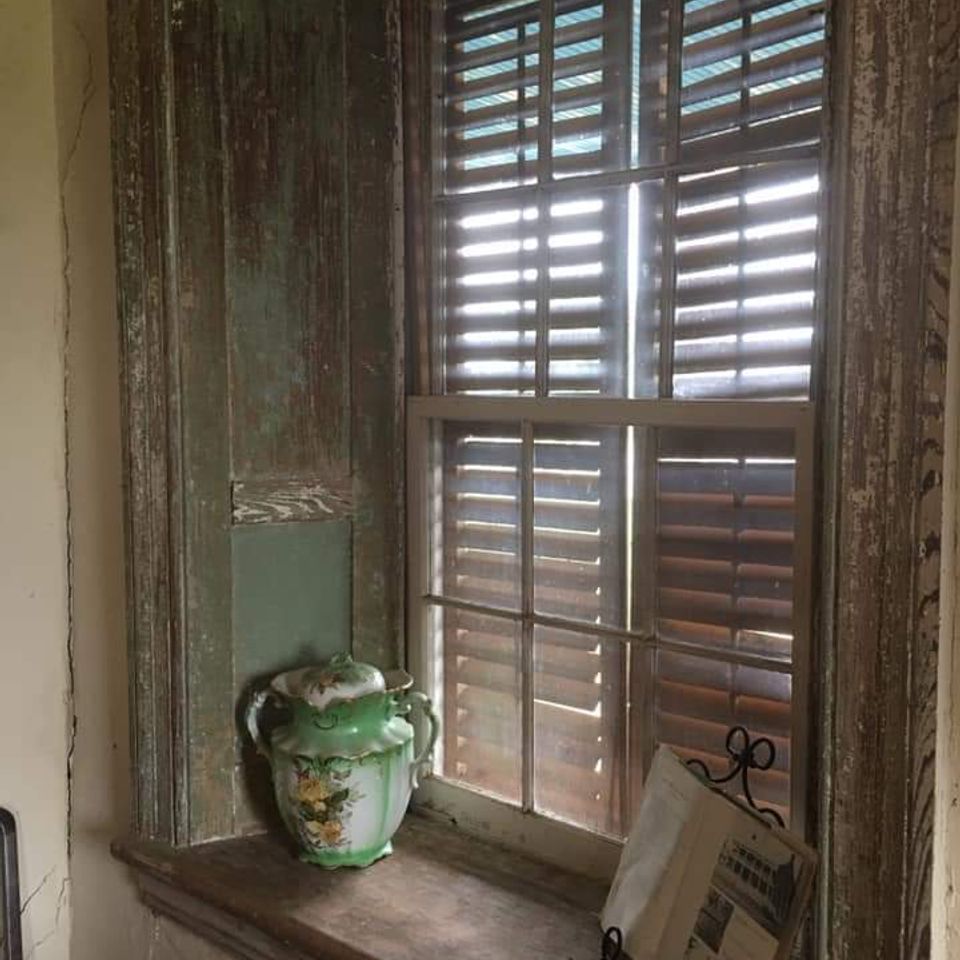

"That old rock homestead is still standing and I guess it is in as good repair as any house could be that was built seventy-five years ago. Sutherland Springs is a good-sized town now and all of the once open range is crossed with barbed-wire fences, highways, railroads, telegraph and telephone lines and every other mark of progress. But I can shut my eyes and see it as I knew it best, and open range on which grazed thousands of cattle, and in the midst of it that big old rock house, a home for everybody that drew rein and a hearty handshake and welcome greeting for both friends and strangers. Times have changed, comforts have given place to luxuries which we accept as a matter of course and enjoy and appreciate, perhaps, all the more when we look back to when we were fortunate to have all the necessities of life.

"I have had what the newspapers call a checkered career, but am still well and strong and perhaps enjoy life more than a lot of folks who came into the world after I did, who have never known any hardship greater than to eat three good meals a day and sleep twelve hours every night of their lives that they were not having a days and they gave Texas some fine, dependable citizens, among whom are the good time elsewhere. Pioneer privations did one thing among many others for us. It taught us to appreciate blessings, to be grateful for the good things that come our way, to accept the less pleasant experiences and never to say die where principle and right were involved. They were good members of the Old-Time Trail Drivers' Association. The trail drivers are representative men of their day and I am glad that I am enrolled in an organization that unsurpassed in what it stands for. The men who put the cattle industry of Texas on the map and created a world-wide demand for Longhorn cattle.

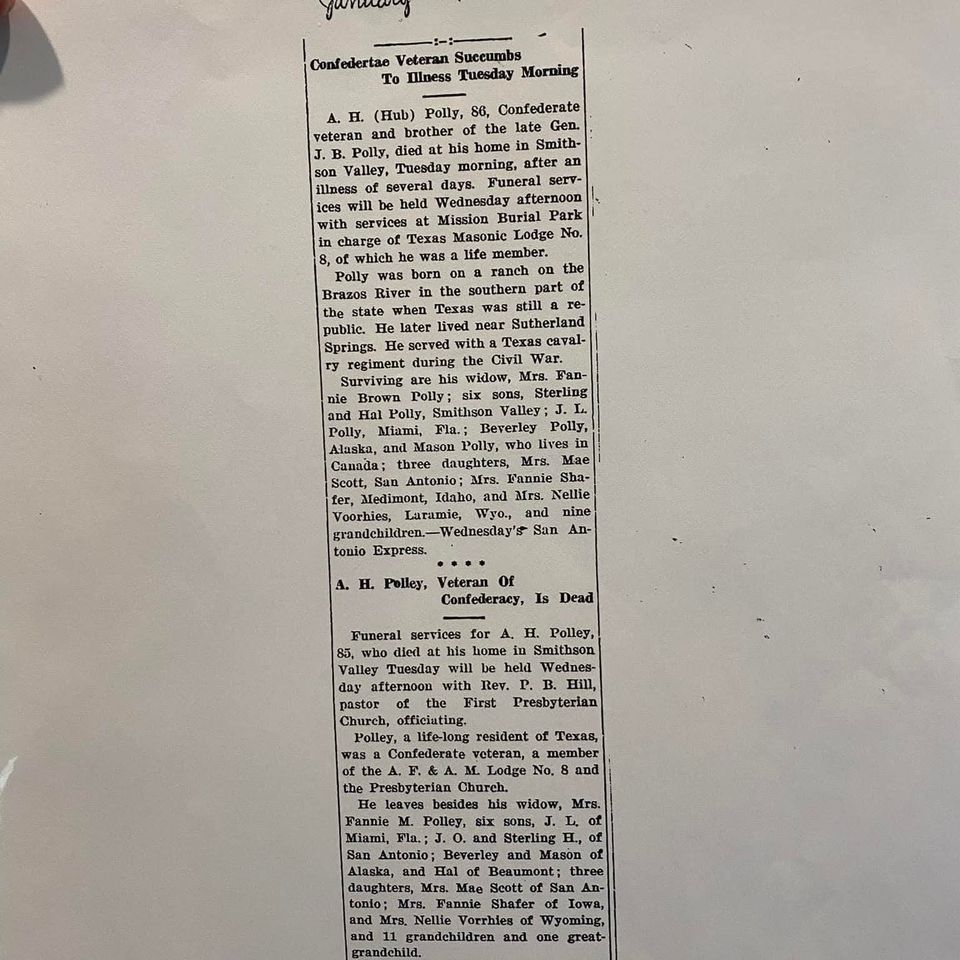

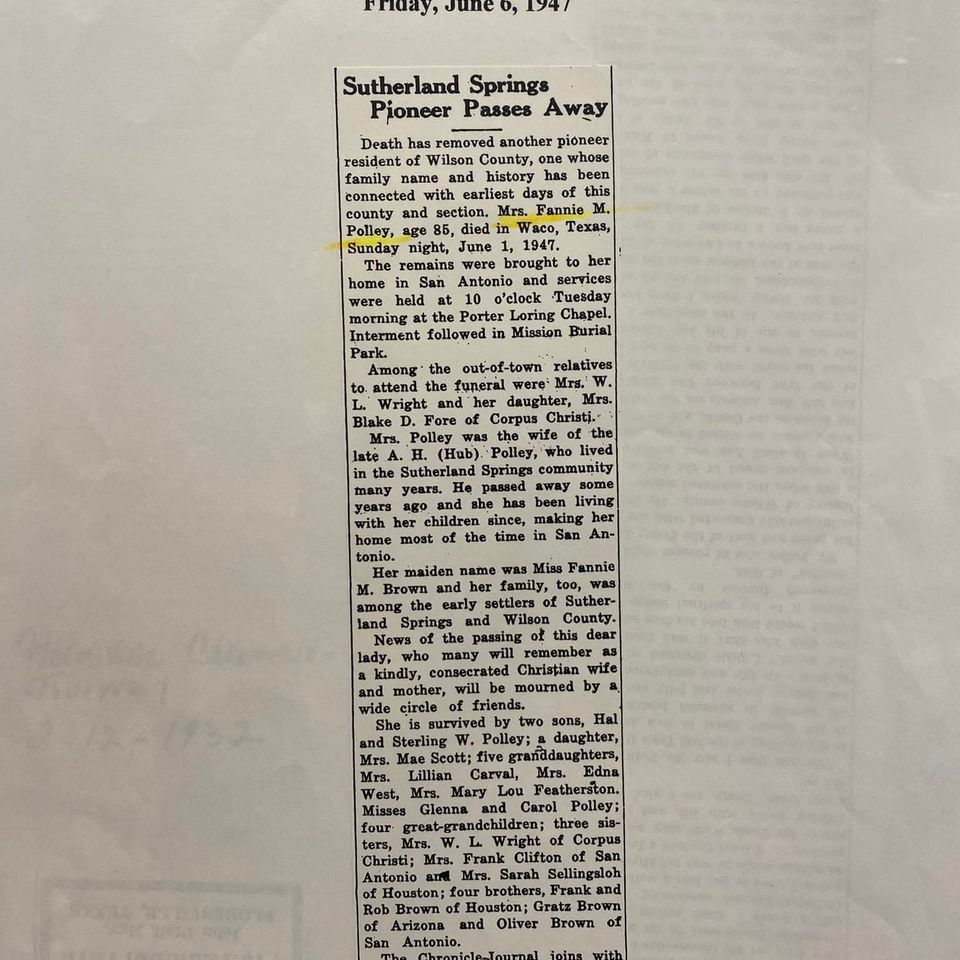

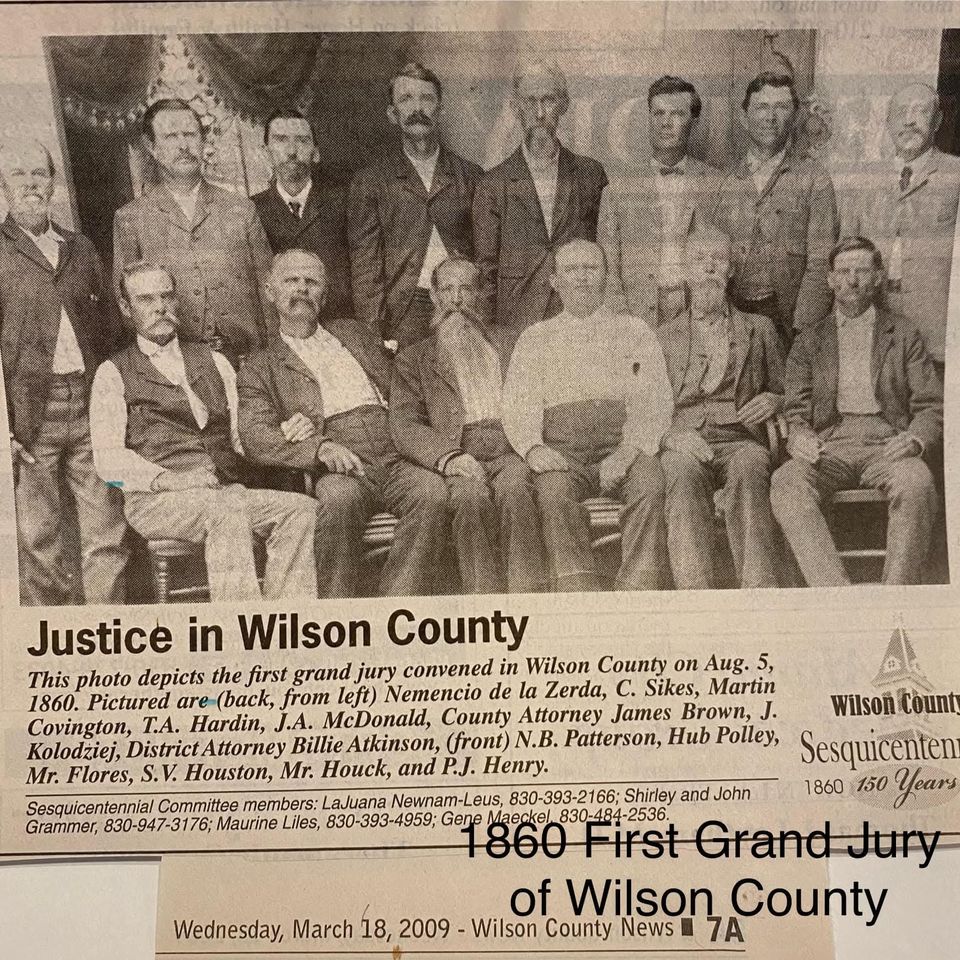

***************