Until the internal combustion engine eventually made them obsolete as the primary mode of transportation, the horse amounted to the Texan's "automobile."

With several generations of Texans now much more familiar with gas burners than oat-powered modes of locomotion, it is easy to think of horses and cars as virtually the same things. But the only similarity is that each, in their day, became the preferred means of personal transportation.

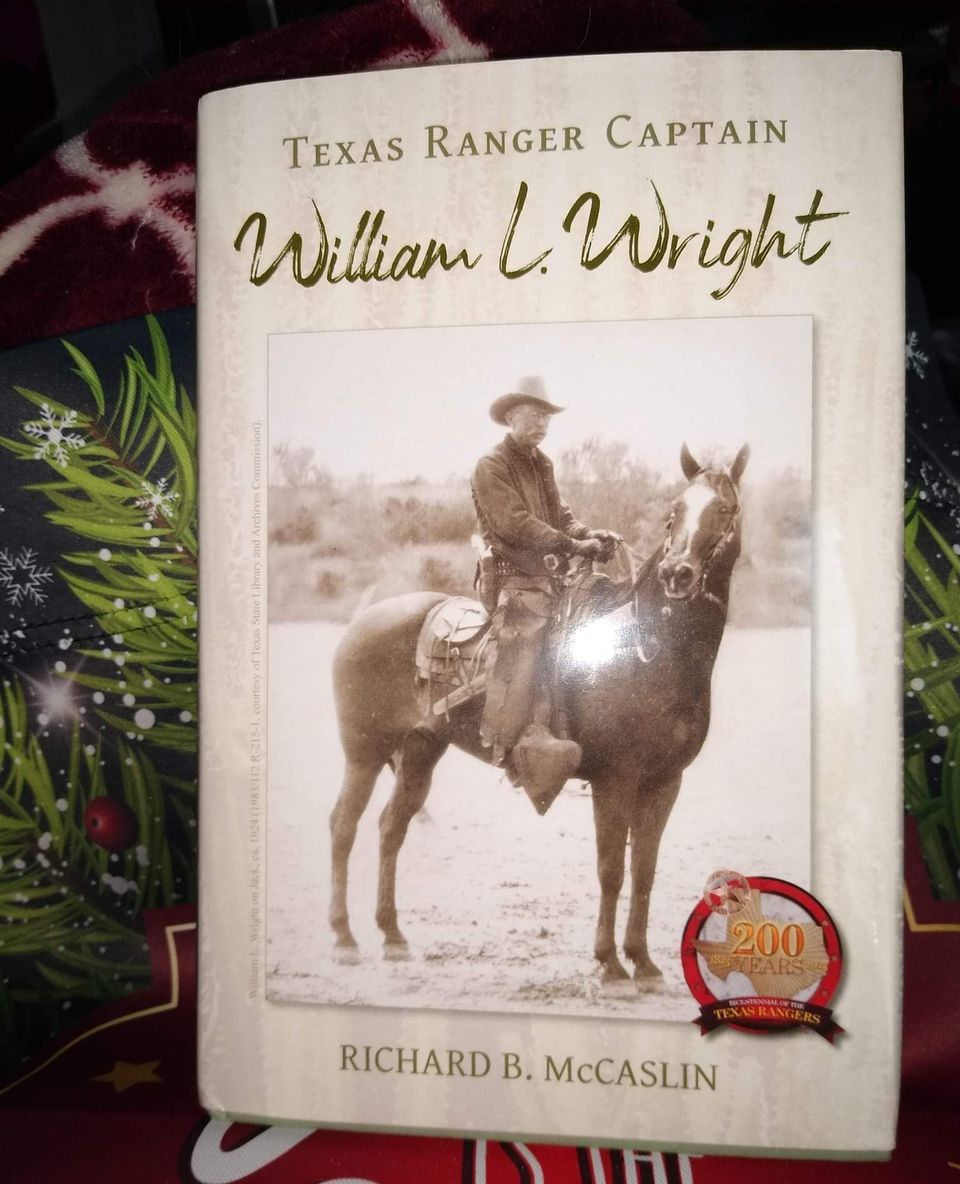

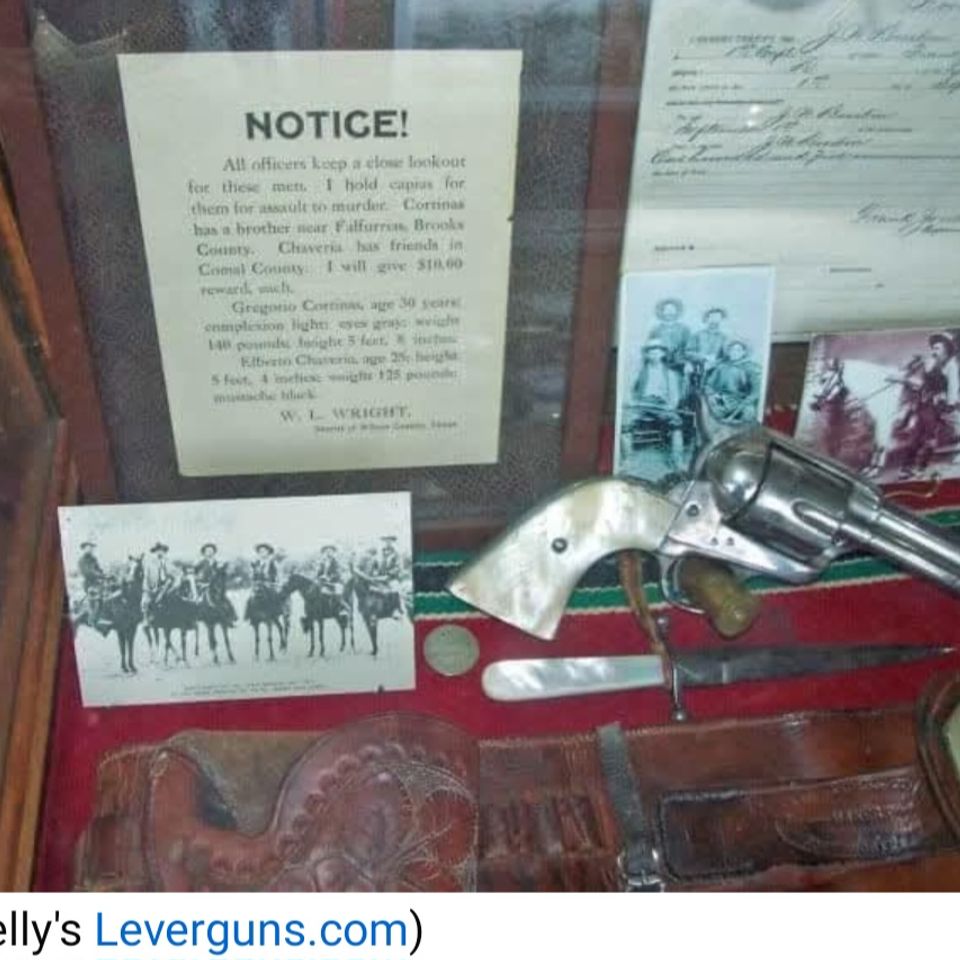

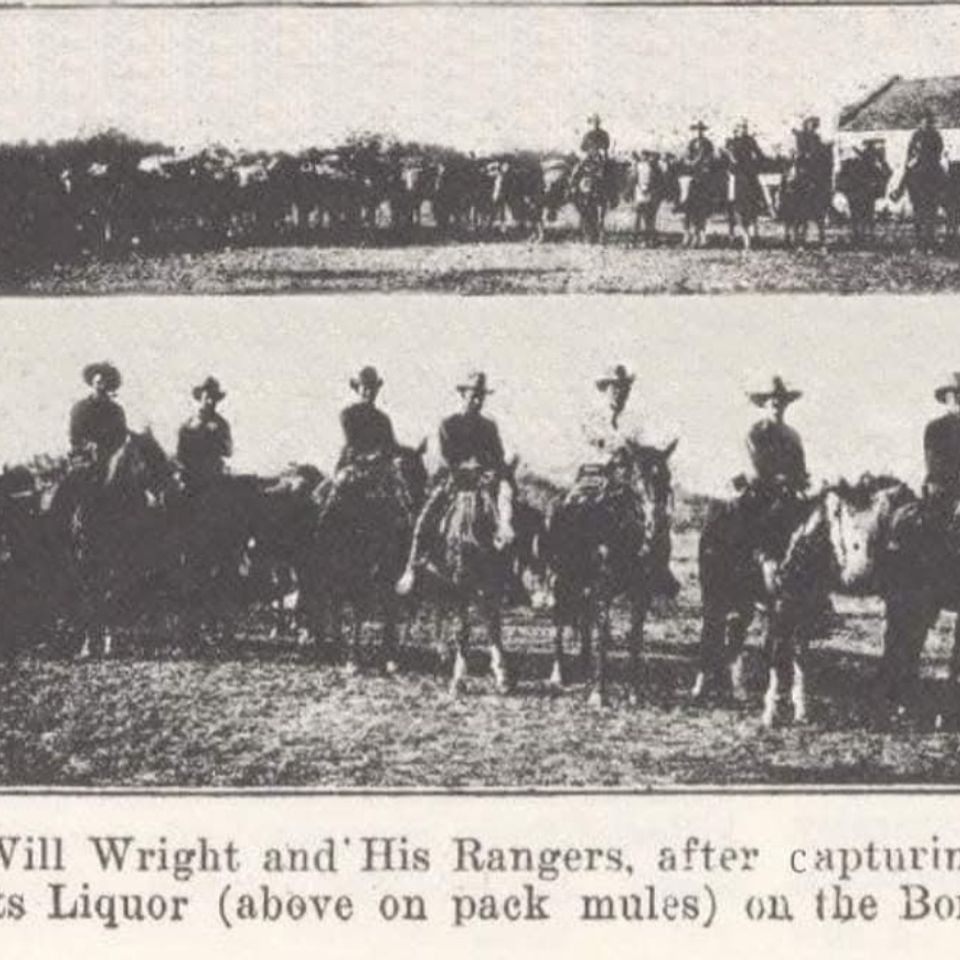

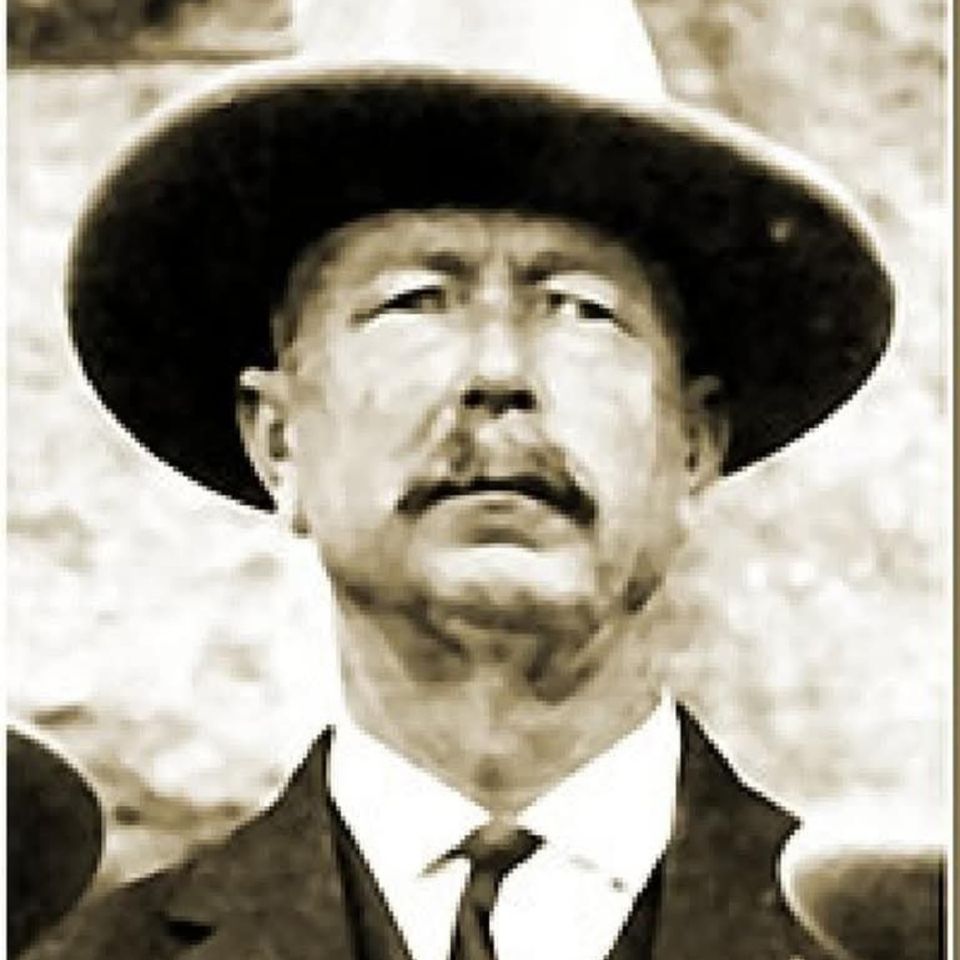

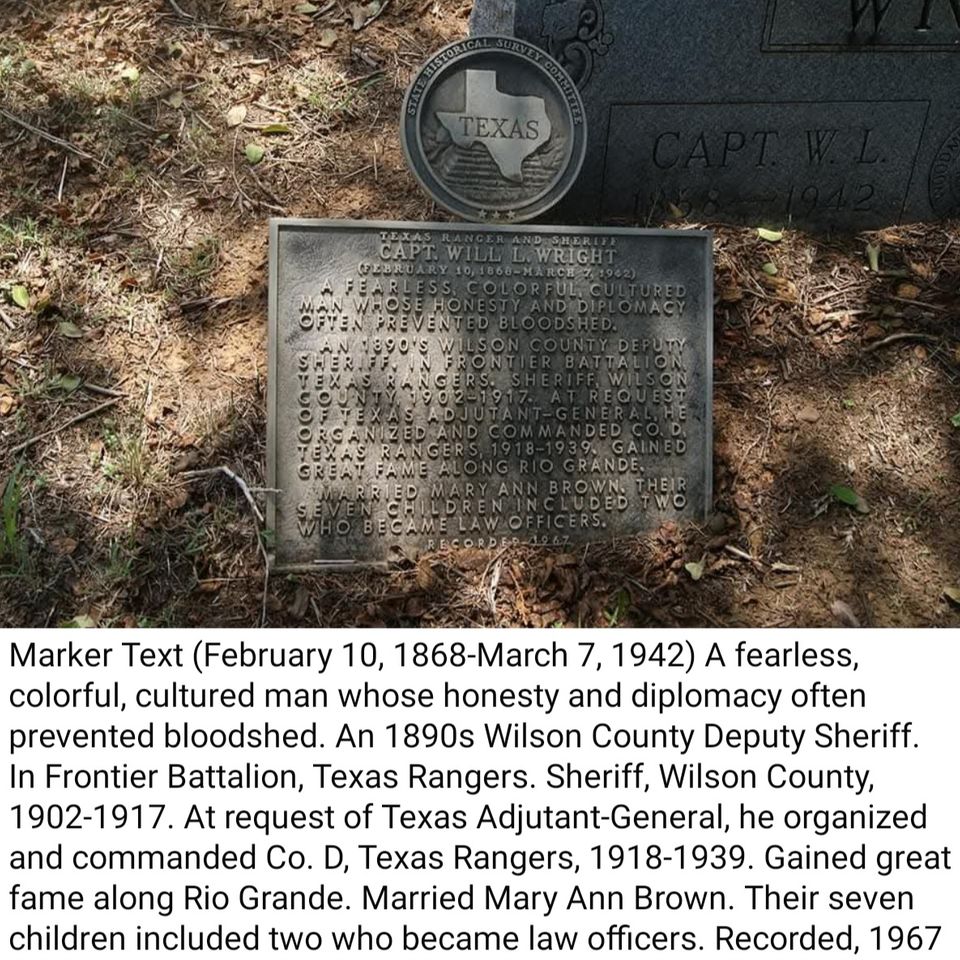

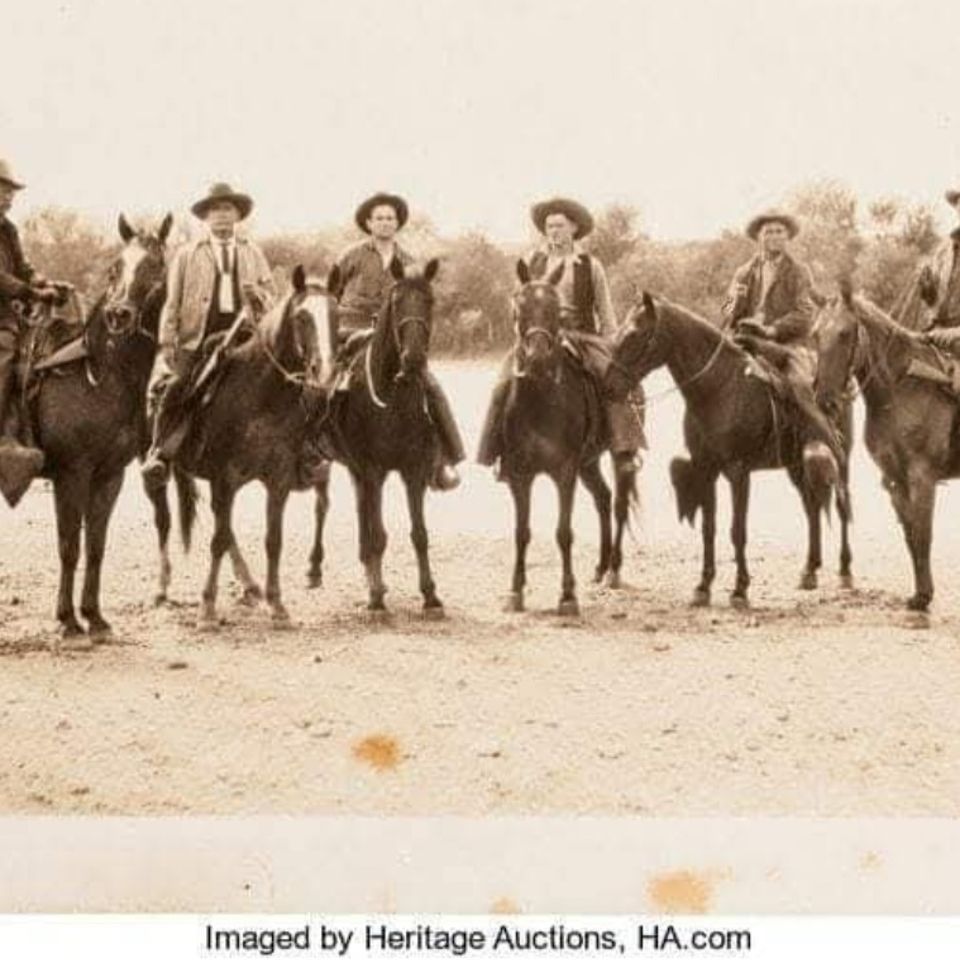

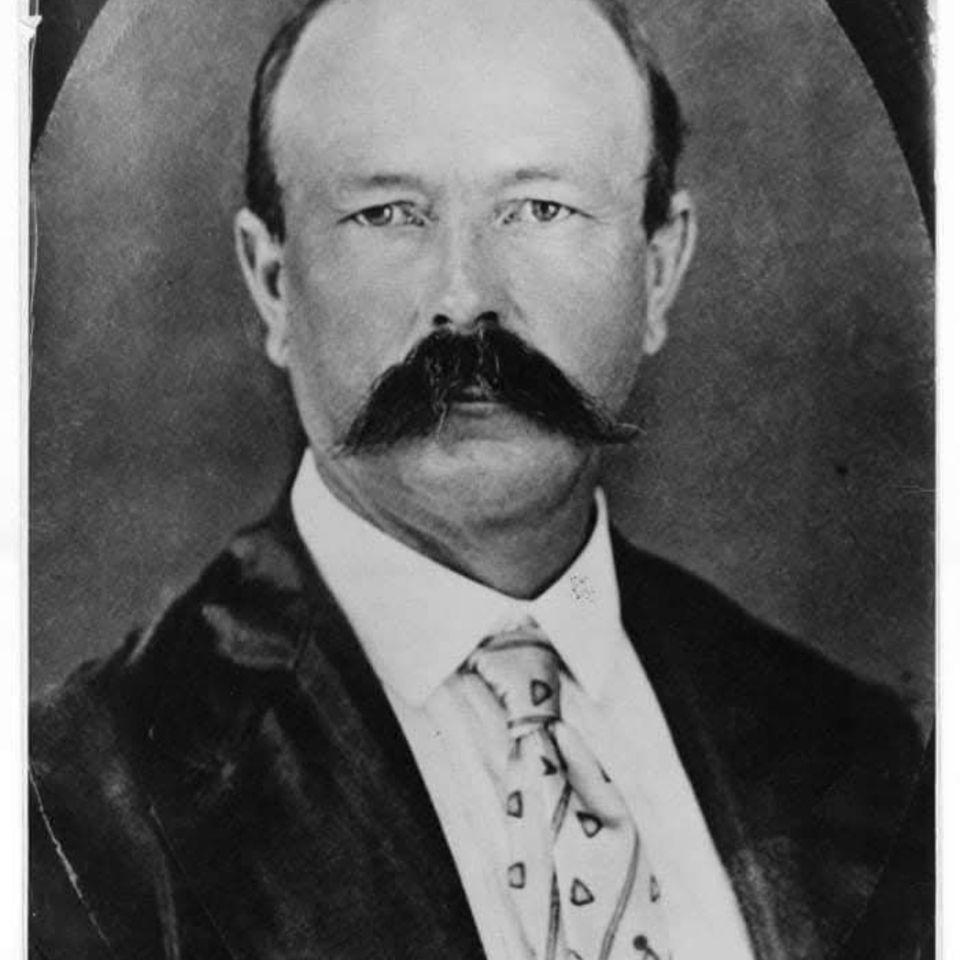

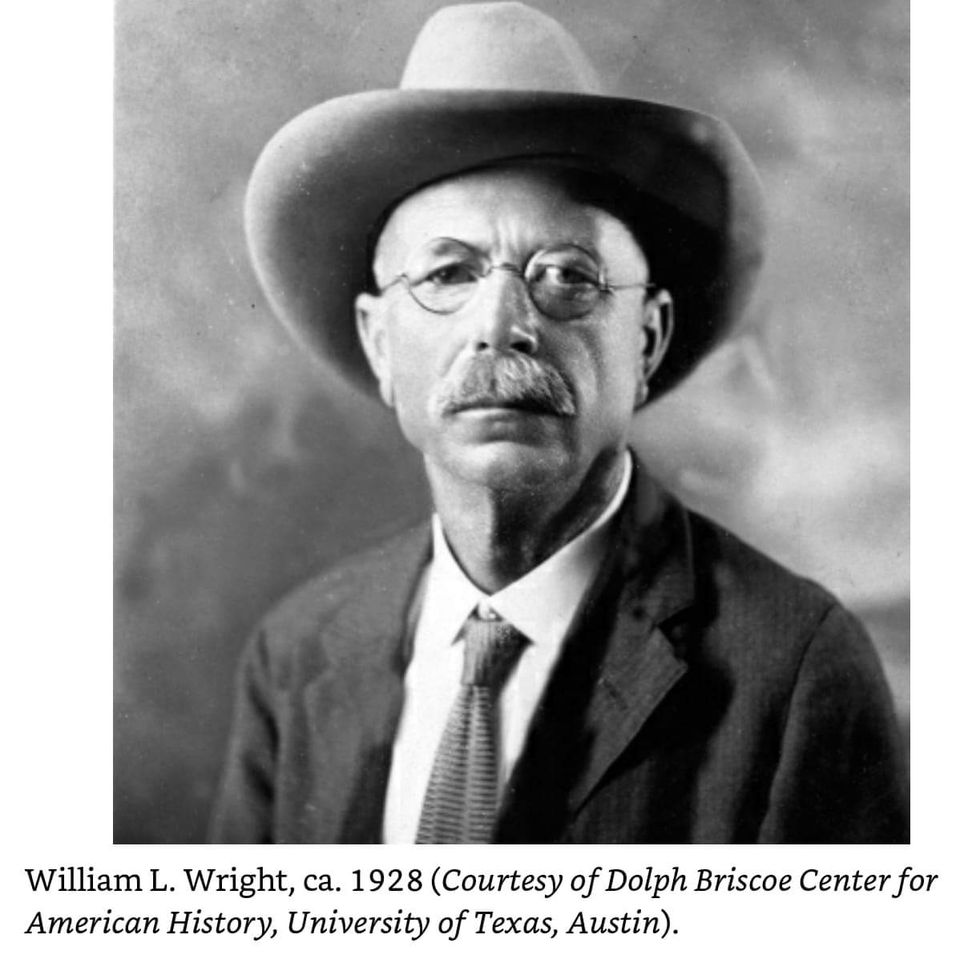

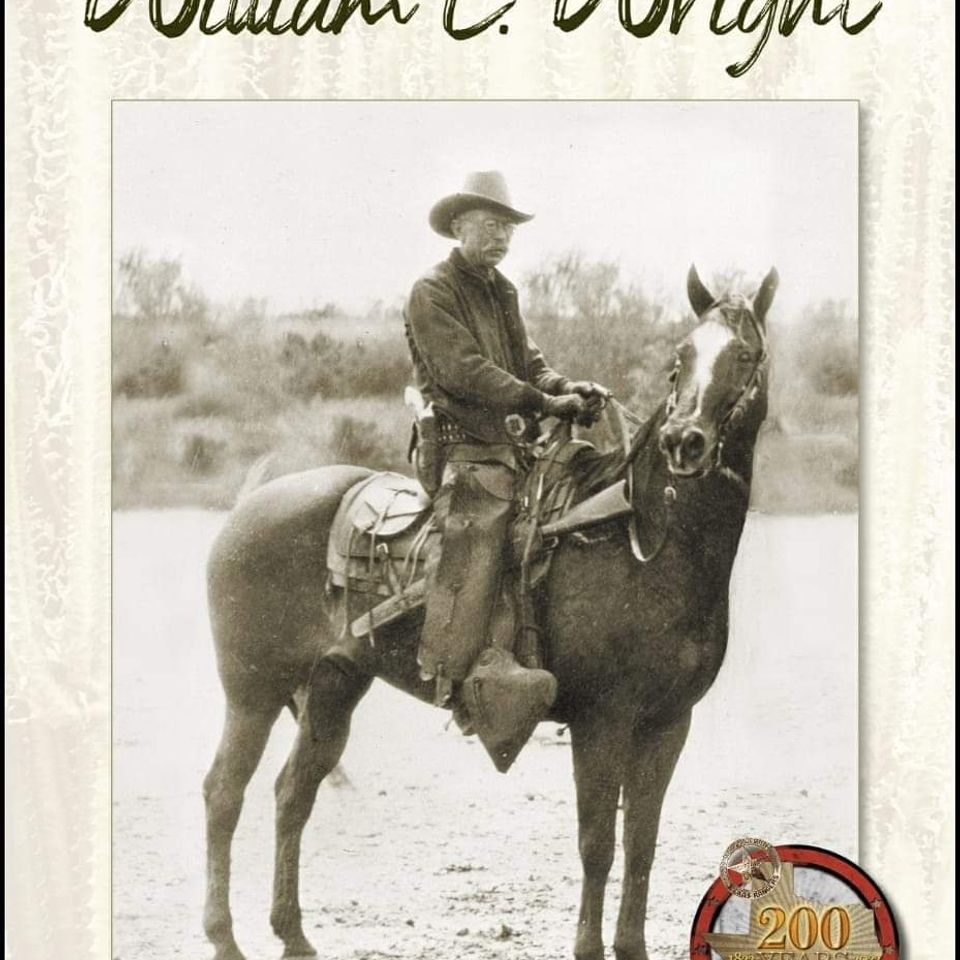

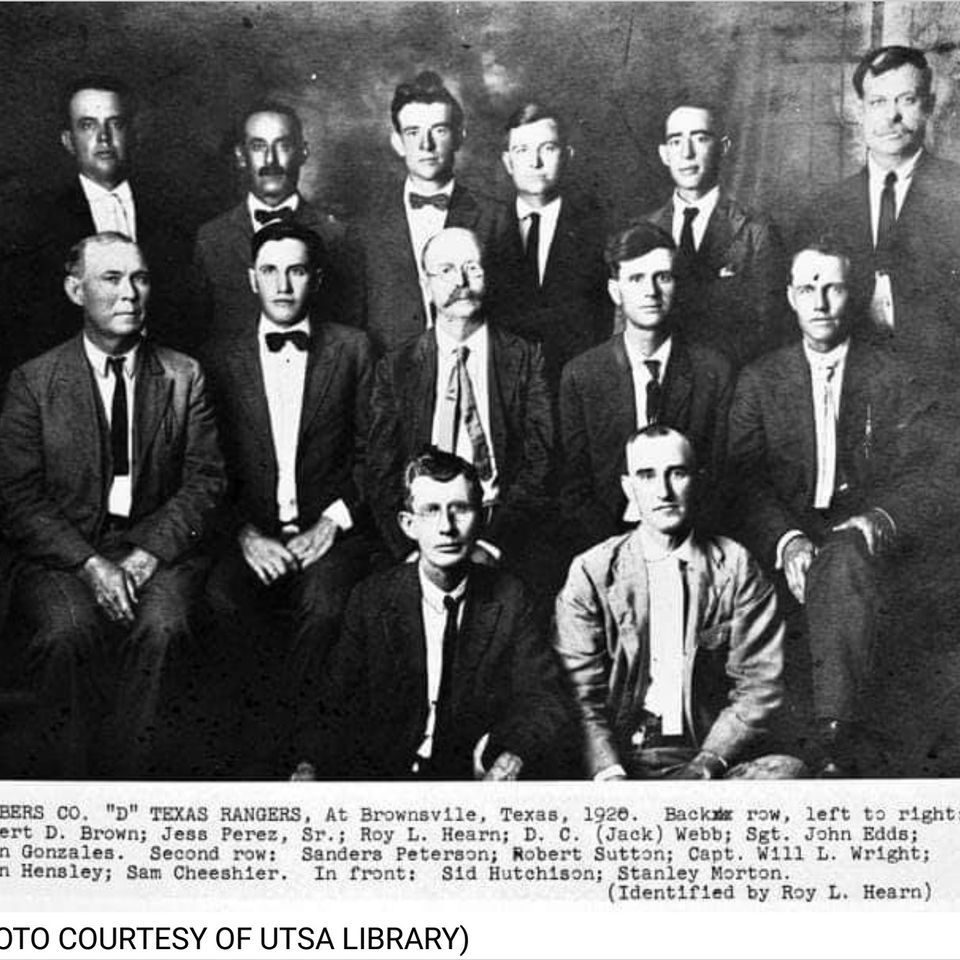

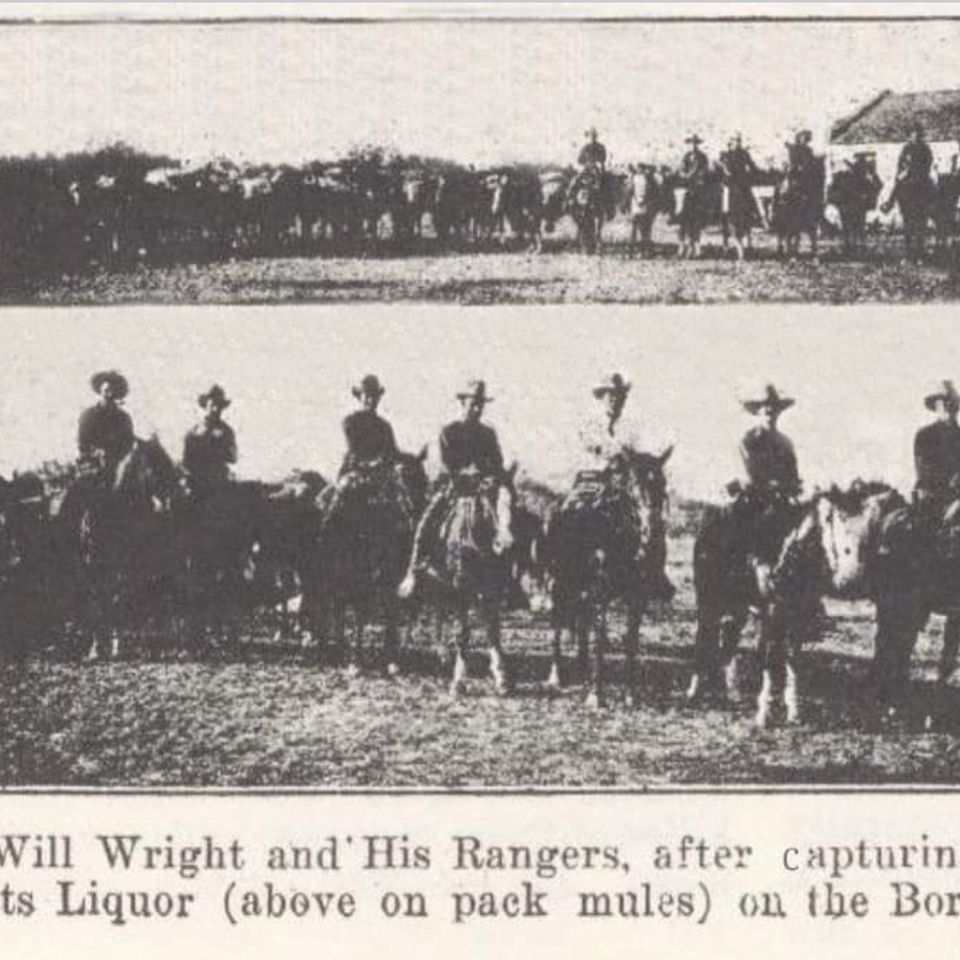

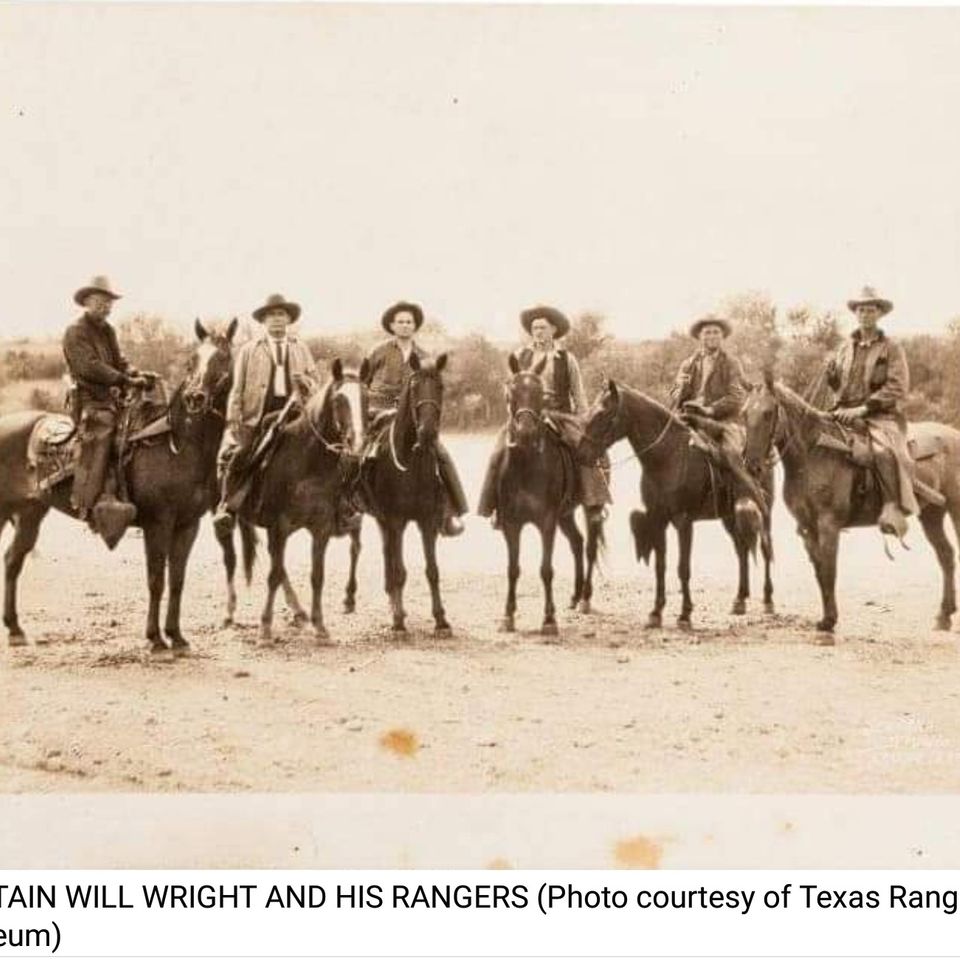

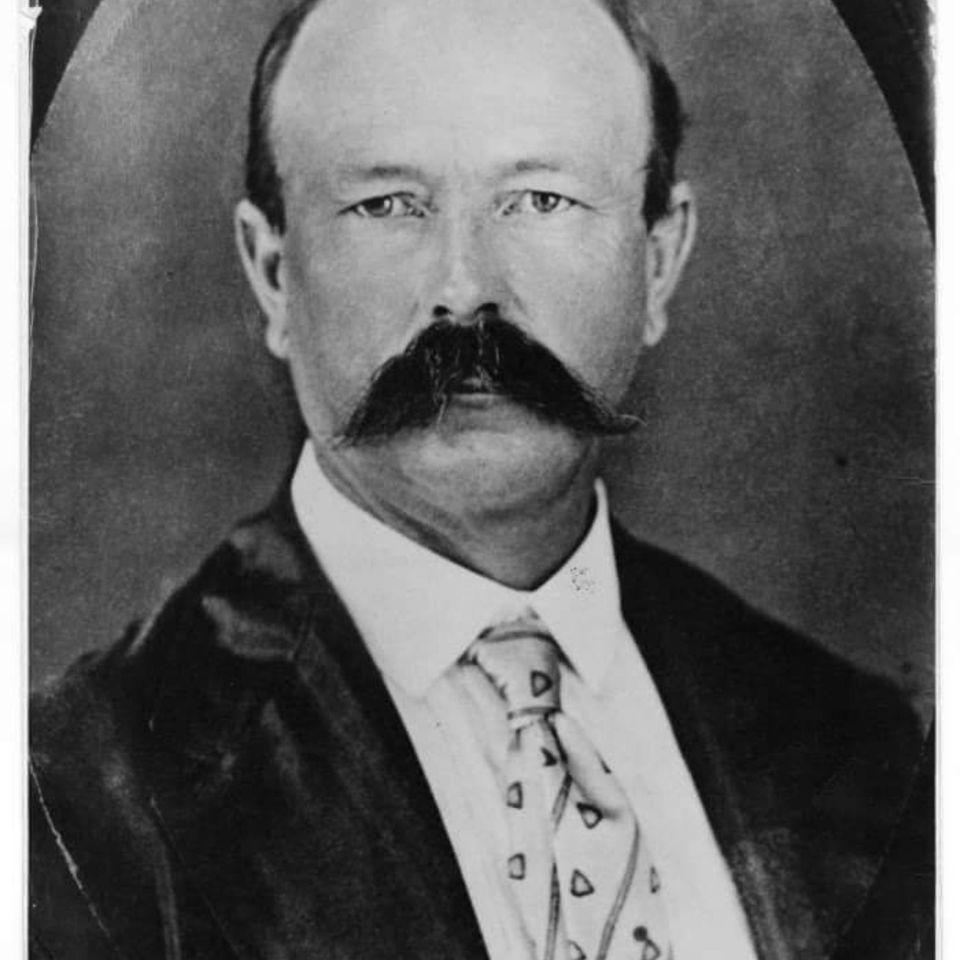

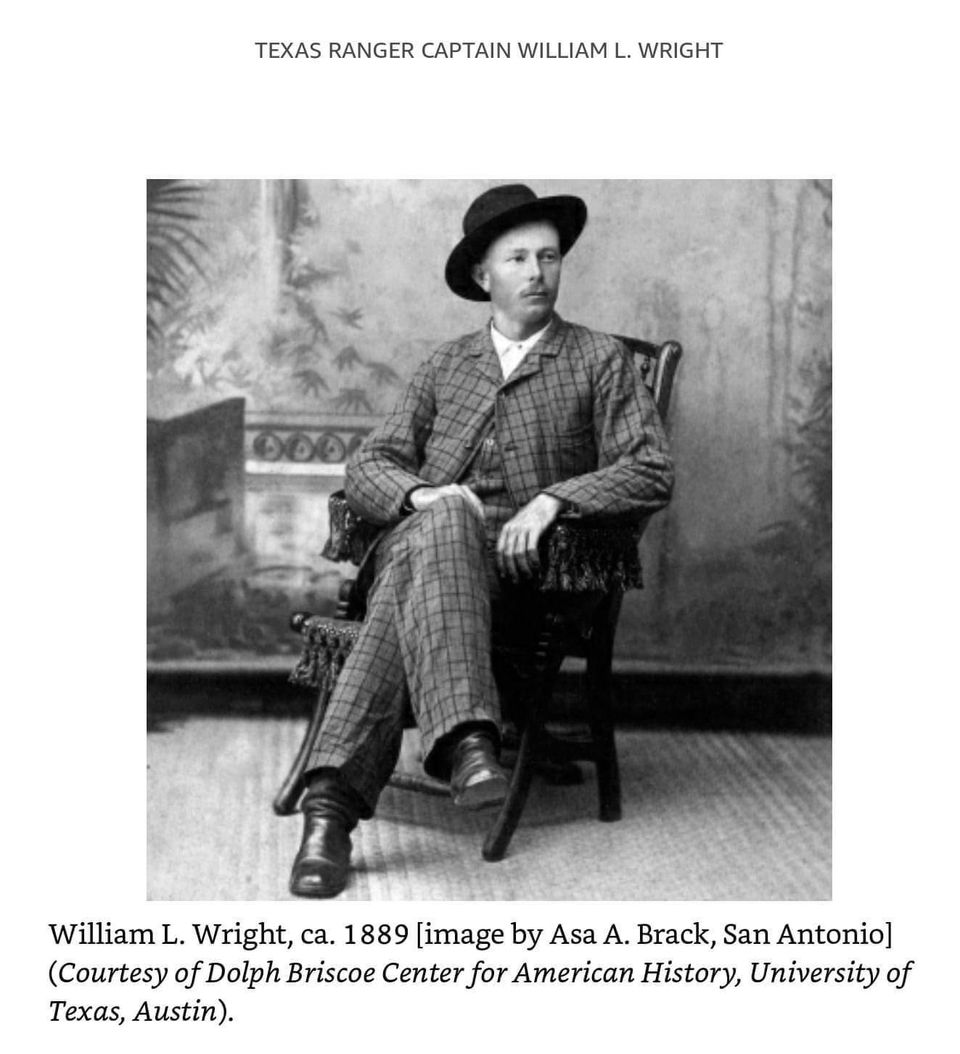

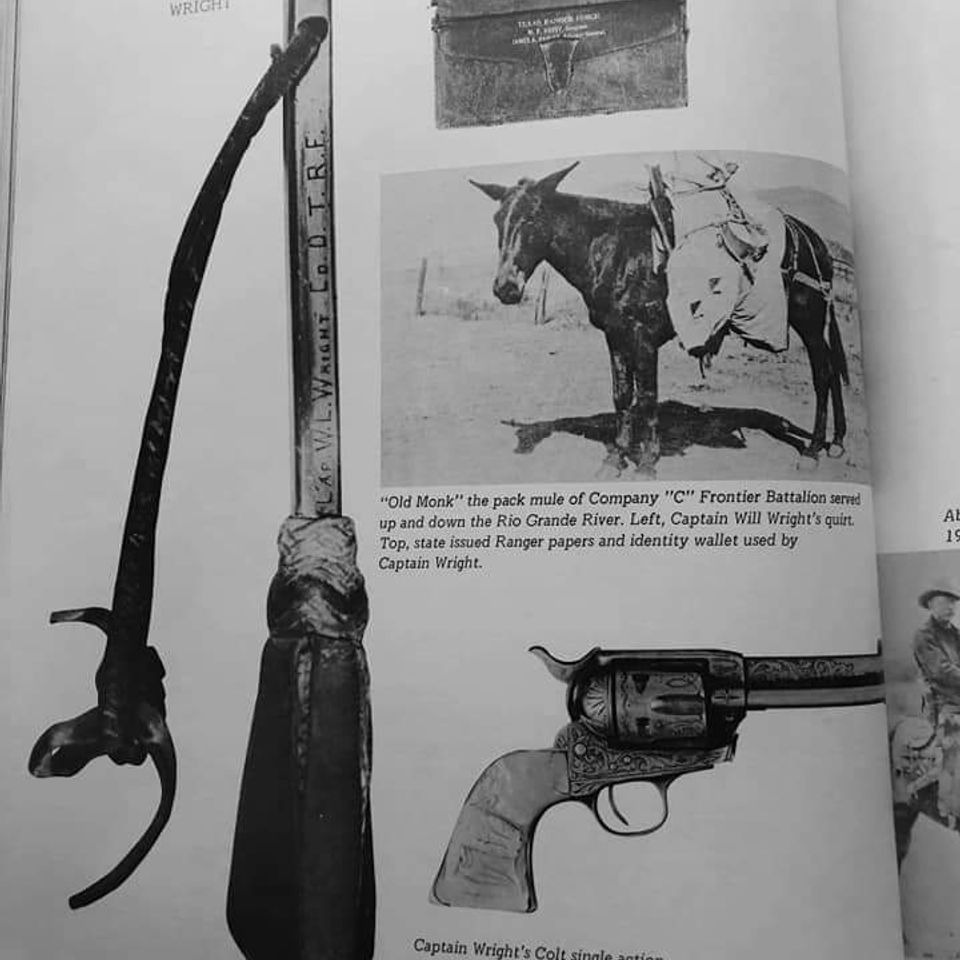

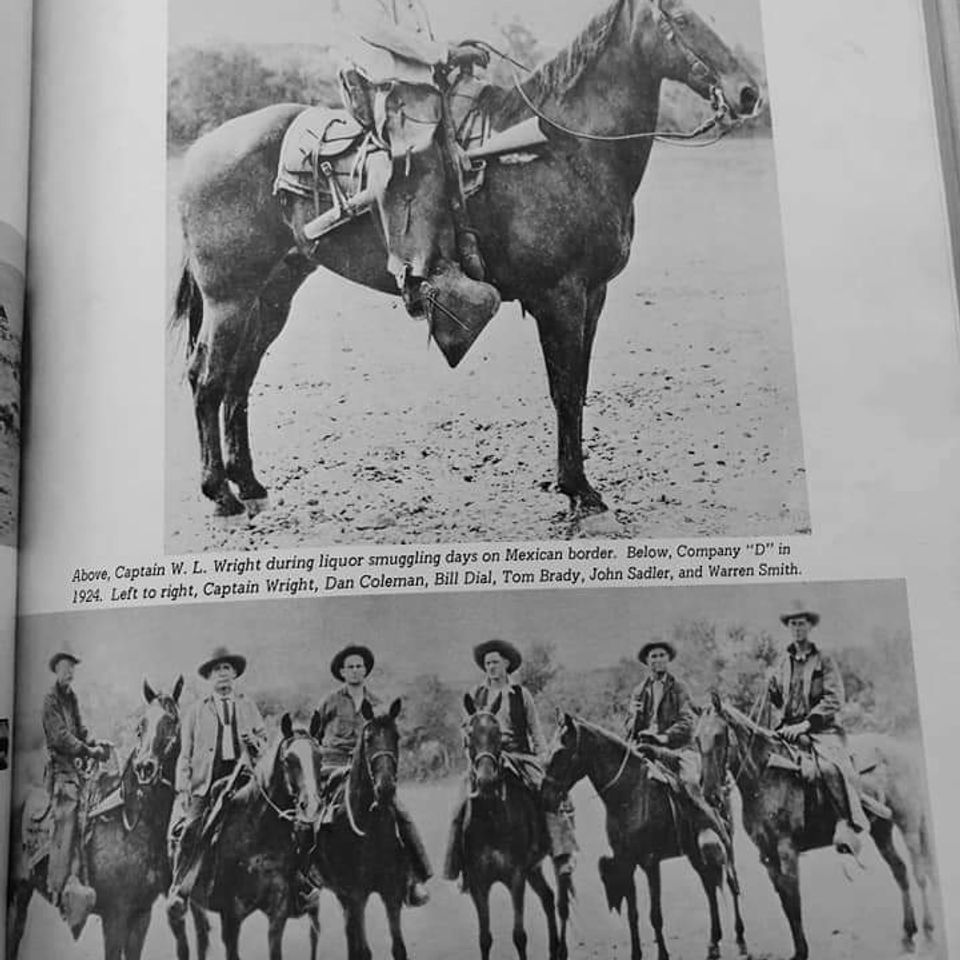

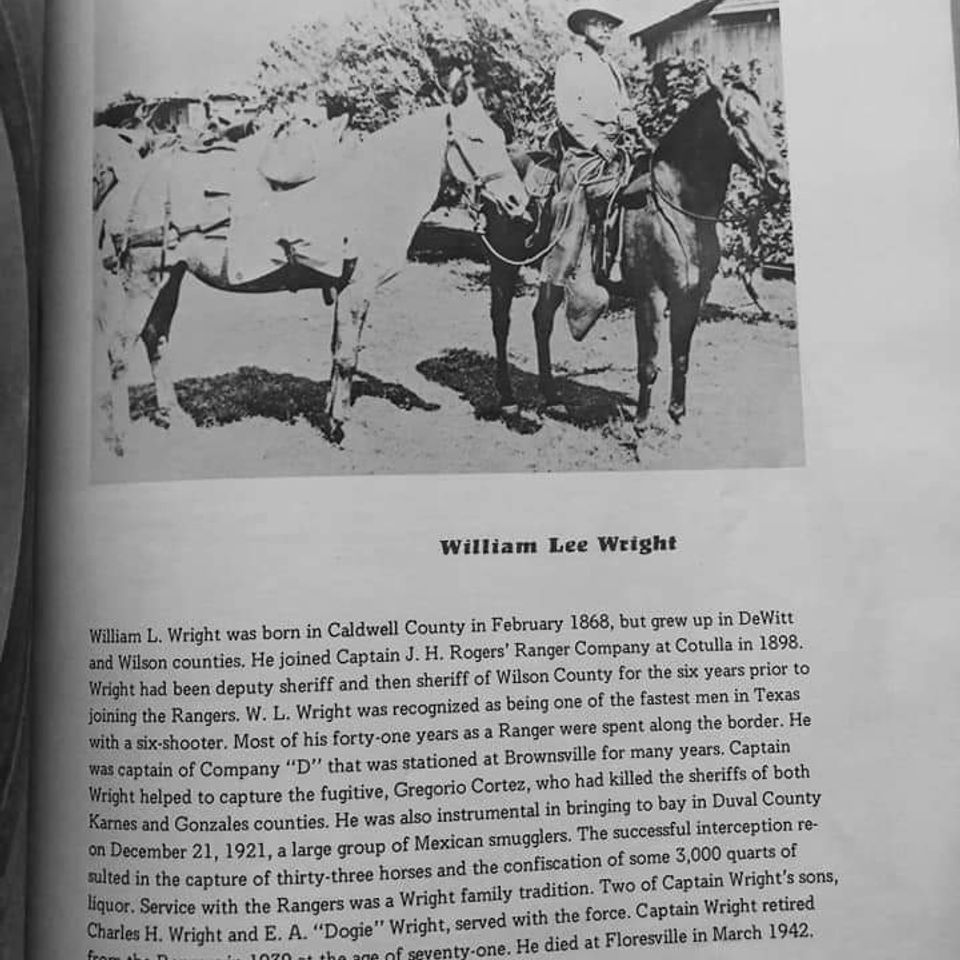

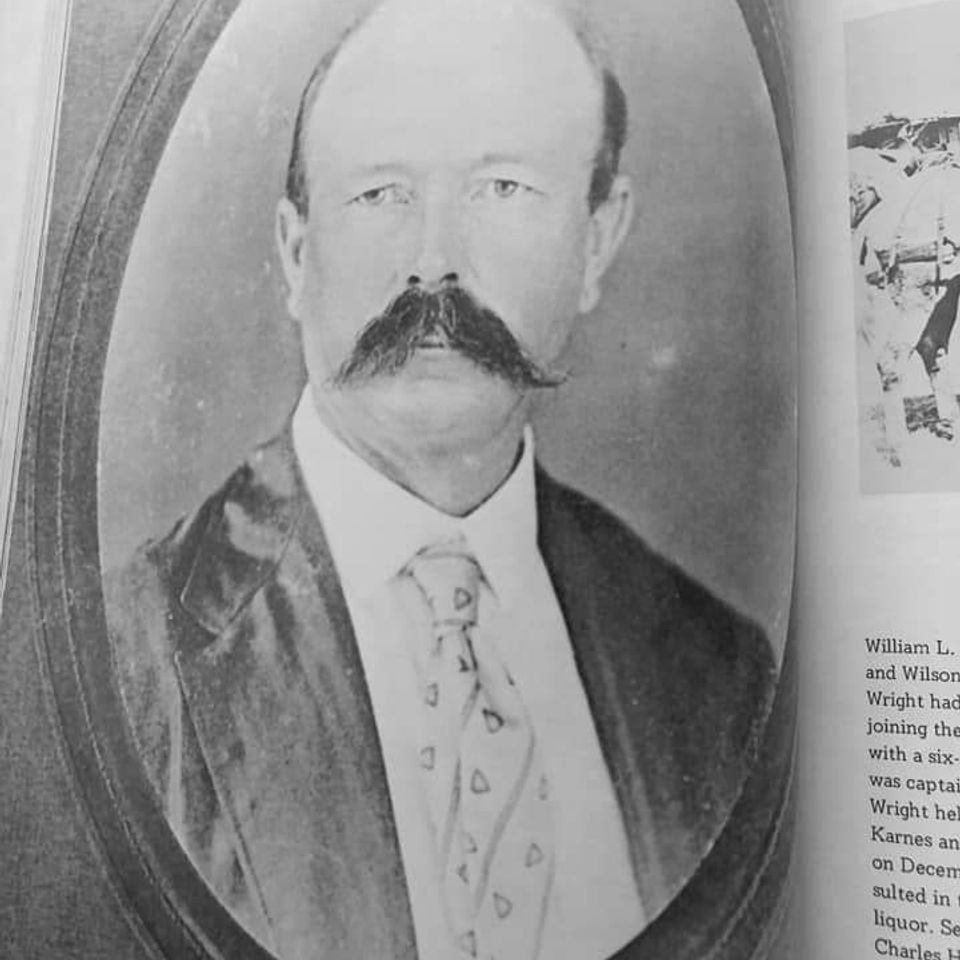

Even after Henry Ford began mass production of his Model T in 1908, Texans who had grown up in the horse era had a hard time adjusting to the new-fangled horseless carriages. Texas Ranger Capt. Will Wright, one of the state's better-known lawmen, reluctantly made the transition from horse to automobile.

Early on, he employed a young man (a civilian) to be his driver. One person who drove for him was the late Bob Snow, who later became a Texas game warden.

"If I drove too fast," Snow recalled, "the captain would tell me to slow down so he could watch the grass grow."

In time, Wright and most other Texans adjusted. But muscle memory takes a while to overcome. Automobiles, some learned the hard way, do not stop when you yell "whoa"!

The portrayal of the horse in American popular culture, of course, has not helped anyone gain an accurate understanding of how those who lived in Texas in the 18th, 19th or early 20th century got around. If you believe most Western movies or television shows, a horse was instantly available and as untiring as a hunk of metal and plastic you start with a key or by pushing a button.

The truth is, as anyone who has read much about the West or spent any time cleaning out a corral could readily tell you, a horse is an animal, not a machine. But they require every bit as much maintenance as an automobile and are a whole lot less forgiving if their care gets short shrift.

One difference between a horse and a car, of course, is mileage.

A person can get behind the wheel of a car, and, depending on how much gas they have in their tank and how strong or weak their own bladder is, can emerge three-and-a-half hours later 200 miles away. With a horse, a good day's ride amounted to 30 miles. Experienced, determined riders on a fine horse could push the distance to 40 and even up to 80 miles.

"Forty miles a day on beans and hay" was a popular expression when an Army cavalry regiment consisted of horses, not armored vehicles or helicopters.

Riding a horse real hard, however, could leave it jaded, or even permanently unfit for riding. Sometimes, an extremely tough ride could kill a horse.

To make it as easy on government stock as possible, the Army liked its cavalrymen to weigh 140 pounds or so. A bigger man was extra work for his mount, not to mention that he made an easier target for any enemy.

The Army way, when on the march, was for the men to be in the saddle 45 minutes of every hour. For a quarter of each hour, the troops dismounted and walked ahead of their horse, giving the animal a chance to rest a bit and cool down. At noon, Army horses on patrol would be unsaddled and allowed to graze and rest. Later in the afternoon, the bugler's "Stable Call" meant it was time to tend to your horse. That had to be done before a soldier had his evening meal.

Speaking of grazing, in fall or winter, anyone traveling by horseback had to carry horse feed (either oats or corn) or depend on some place that had an available supply. In the spring, a hardy horse could get by on native grass, assuming it had not been spoiled to oats or corn.

Those who prevailed in early Texas were people who learned how to best handle their horses. Generally, Texans could outride poorly-training and sometimes ill-mounted federal troops. Comanches, often described as having been the finest light cavalry in the world during their heyday, could sometimes outride either soldiers or Texans.

No matter how skilled the rider, a horse could not go faster than a gasoline-powered vehicle. But perception of speed is another thing.

Texas storyteller J. Frank Dobie, who as a young man spent plenty of time in the saddle, had this to say about the difference:

"Although machinery has reduced miles to minute decimals, it has not reduced the sense of speed felt by a horseman and shared by his horse. A running team of mustangs hitched to a buckboard will give the rider more sense of motion that the fastest automobile on a straight concrete road."

And a bag of feed costs a whole lot less than a tank of gas.

(Courtesy of Mike Cox from "Texas Tales" June 18, 2019)